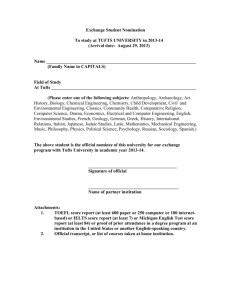

"Doing Business in the Information Age” given at the DMA [Direct

advertisement

© 2008 Digital Collections and Archives, Tufts University "Doing Business in the Information Age” and Questions and Answers segment at the DMA [Direct Marketing Association] Annual Financial Service Conference on 8 June 1989 in New York, New York Walter B. Wriston: Most of these futurists tend to use a straight-line projection of today's data to paint a picture of what tomorrow will look like in their view. My favorite illustration of this straight-line projection is the recent statement, one of my friends made, that if George Steinbrenner continues to behave as he has as in the past, 70 percent of the male population of New York will have managed the Yankees by the year 2000. -(laughter) -- I suggest to you that in the real world, things rarely continue on such a steady track, but even to suggest to most people that the world may be very different in the future is usually met with disbelief. Examples abound. When the price of oil was headed up from $30 a barrel, those who suggested that it would hit $15 a barrel before it hit 50 were dismissed out of hand. This scenario simply did not fit with their projections, and yet, as you all know, that is what really happened. The business of data processing and information is no exception. Some of you in this room may remember, when the experts so-called predicted the rise of huge computer utilities which would supply data processing to American business, much in the same way that the familiar electrical utilities supplies current and distributes power, this projection which was very common never happened. Indeed, the world went just the other way. The advent of the PC and the work station based on powerful new microchips changed not only how we do our work, but in many cases, the nature of work itself. The data center manager, who in the early days of information technology was a kind of a technological gatekeeper who practiced some arcane art, but that person has now moved into the mainstream of American corporate management. The diffusion of computing power tied together with networks that lets one literally access thousands of databases is having a profound impact not only on business, but on government and, indeed, on the very concept of the nation state. Leaving aside for a moment some of the profound political and social changes being driven by information technology, what do these rapidly changing technologies mean for our business? The scope of the revolution through which we are living is so broad and so deep that it is fair to say that almost everything that we do, and the way that we do it, has been or will be soon impacted. At this conference and before this audience, it might be most appropriate to start with a discussion of marketing. In thinking about marketing, one often gets back to some of the aphorisms that made Ted Levitt famous. One of these that comes to mind was that he said: "There is no such thing as a commodity. All goods and services can be differentiated and usually are." Now whether you agree or disagree with Ted Levitt, I think most of us would acknowledge that there is at least a grain of truth in that statement. And if differentiation is the name of the game, how then can we use the modern information technology to enhance our market share? In trying to think through this problem, one is chasing a very rapidly moving target. Today, the nature and size of the market for just about everything is changing at an accelerating rate. Old benchmarks are © 2008 Digital Collections and Archives, Tufts University 1 © 2008 Digital Collections and Archives, Tufts University shifting and new strategies are required. Competition has moved from next door to anywhere in the world. Suddenly, we are finding that the world class competition can, and does, come from areas that posed no threat to us only a few years ago. It has now become a cliché to say that we live in a global market, but I suggest to you, that even though innumerable speeches are made giving lip service to the idea, many people still truly fail to grasp this new reality and they continue to operate their business in the same old way. But the very framework of economic analysis is changing. All economic models from Adam Smith to the present are based on the concept of a national economy of a sovereign state. While there may still be some national economies, there is also a world economy. And the relative impact of the world economy on individual nations is growing every day. Borders have become porous, and money and ideas move over and through them with the speed of light. No one who has watched with amazement the action of the Chinese students on television can fail to understand that the new technology has placed powerful weapons on the side of freedom. While the immediate outcome in China is not promising, the ultimate outcome is almost assured over time. This reality is creating many wholly new situations with which we will all have to deal. One of the new realities is the speed with which technology moves from the mind to the marketplace. It used to be that there was a long lapse between the time something was invented and on when a practical use in the market was found for it. One would think, for example, that when gunpowder first appeared on the battlefields of the Western World, this powerful new force would immediately have been applied to civilian construction like building tunnels and so forth, but the world waited almost half a century before the technology of gunpowder moved into the civilian sector. The conventional wisdom almost always rejects new ideas. Two other examples serve to make the point. Over 200 years ago, in 1775, a Frenchman named Duperron and an American called Bushnell both made significant inventions which were destined to alter the balance of power by changing the way wars were fought. Duperron invented the machine gun and Bushnell the submarine. But despite the constant clamor of all military men for ever increasing destructive power, both inventions were basically ignored for 100 years. At the start of World War I, the famous British Field Marshal Douglas Haig opined that the machine gun was "a grossly overrated weapon" and his French colleague, the Director-General of Infantry, told the members of the French parliament that "this weapon will change absolutely nothing." Mr. Bushnell's invention of the submarine fared no better. Even such a futurist as H.G. Wells, as late as 1902, said that his "imagination refuses to see any sort of submarine doing anything but suffocating its crew and foundering at sea." Now such misjudgments about the usefulness or the impact of technology are the stuff of history, but they should serve to remind us not to dismiss too quickly contemporary ideas that seem at first to be either impossible or useless. This is as true in your business as in politics. As business and government bureaucracies expand and age, they tend to develop a kind of an administrative arthritis -- they move slower and they are less agile in response to the market demand. To give you a few examples, the commercial banks of this country should have invented the credit card, but they did not. Kodak, which is always at the forefront of technology, was a natural to produce the first instant camera, but it was Dr. Land of Polaroid who brought an idea to © 2008 Digital Collections and Archives, Tufts University 2 © 2008 Digital Collections and Archives, Tufts University market. General Electric should have been the world leader in computers, but it was IBM, without a single electronic engineer on their payroll in 1945, that saw the opportunity and seized the lead. As it happened, all these companies survived, but the corporate graveyards of the world are littered with other companies that refused to assess the market potential of a new technology. And instead created what we all do, we create a committee called a technological assessment committee without ever thinking about what does the market want. The list of good companies who turned down the Xerox process reads like the Who's Who of American Industry. Even today, marketing people are often left out when technological assessment committees are formed. This is true even though we know for a fact that scientists are often not a good judge of the market potential for their inventions. Even inventors themselves fail to see it. Edison, for example, dismissed the phonograph which he invented as an instrument of no commercial value, because he failed to perceive that there was a market for recorded music. A learned committee making a "technological assessment" of a low-tech concept of selling a common, garden variety rock in a cardboard box would have turned the idea down out of hand; but a clever package, an improbable set of instructions, and the pet rock was born. In the last ninety days of 1974, one million three hundred thousand pet rocks were sold at $4 each to otherwise rational citizens. -- (laughter) -- The Japanese also weighed-in on the market with a fad product. A man called Hakuta developed a rubber octopus named the Wacky Wall Walker which generated, according to news reports, a profit of $20 million on $50 million of sales. Not a bad market. Now, while neither of these fads lasted very long, somehow a commodity product was differentiated in the marketplace for a time. In this case, the technology employed was the imagination of a marketing mind. But fads aside, today's technology, if intelligently applied is helping to build solid market positions in everything from banking to merchandise retailing. And it is being used by many companies, at both the front end and the back end of the process -- that is from design to delivery. J.C. Penney is one company which has made a very productive use of information technology to let that company do more business, in a better way, in more places. Everyone of us who has ever tried to market anything knows that the closer one gets to the customer, the better one's information is about the consumer's likes and dislikes. So in the ideal world of management text books, the store manager who knows the community in which their shops are located should be able to pick out the merchandise assortments most pleasing to the local tastes. If their judgment is correct, sales increase, markdowns decrease, and profits rise. The problem has been how to maintain the leverage of a huge buying power of a central office, while at the same time letting store managers make a merchandise selection. Penney built a direct broadcast telecommunications system that links together all of their stores. The system can be, and is used for inventory control, reorders, accounting and all the standard business purposes. But that is only the beginning. Currently, store managers gather in centers close to their stores to view a television screen on which appears the latest merchandise picked out by the buyer in headquarters. Standing in a Penney TV studio, the buyer displays a dress, or sweater or another item, describes the material, the price and delivery times, and, then in effect, asks for orders. The enthusiasm, or lack thereof, for an item reflects each store manager's assessment of his or her marketplace. Heavy sweaters may be a hot item in Minneapolis but of no interest in Houston. The order system itself is basically paperless © 2008 Digital Collections and Archives, Tufts University 3 © 2008 Digital Collections and Archives, Tufts University and as a vast simplification over the many layered process which used to exist. From a management point of view, the store manager can no longer excuse substandard store results by complaining that some buyer sent out a poor merchandise assortment that has no or little appeal in his or her particular marketplace. Today managers can be held accountable, while at the same time each store benefits from the mass buying power of the central office. Technology, in short, has permitted a widely dispersed organization of some 1,400 stores to follow a customer-driven business practice with mass marketing clout on buying, and gain a very real business advantage. So once the goods are on the shelf, electronic technology can move directly into the marketing process. It’s not too much of an exaggeration to say that there is a revolution in the way in which information about what people are buying is being collected, collated and used in marketing. The awareness of this opportunity has spawned many new companies. According to a recent issue of the "Economist" magazine, "Today companies spend some $5 billion world-wide hiring outsiders to study advertising, markets and public opinion. Half of that sum is spent in the United States." In our country today, over 90% of American goods now have a universal bar code, which is that familiar black stripe known as the bar code. The productivity involved in using scanners at the checkout counter is enormous, and today over half of American supermarkets use that equipment. But the information created by the scanners about what products are sold, in what volume, from what shelf, in what store, to what kinds of people, create a marketing database which is entirely new both in its scope and its usability from anything that we have seen in the recent past. The long run impact of this kind of data on broad-based advertising on television or radio spots is something that we do not yet fully understand, but we do know that supermarkets are moving to in-store advertising, which is said to be growing at 20% a year. A new company has just sprung up using a direct broadcast satellite to furnish music to shoppers, but interspersing the music with custom-made spots tailored to a particular store in a particular market to sell a particular product. There is even a company at the moment market-testing a shopping cart carrying a small eight-inch television screen. When the shopper passes a sensor it interrupts whatever program is playing on the tape and sends out a five-second commercial. Now whether or not this relatively high-cost marketing gimmick will work no one knows at this point, but it is symptomatic of the kind of shift that is taking place in marketing consumer products close to the point of sale rather than in the public media. It’s a short step from this to using the information to optimize shelf space for certain products. The next logical step in the process is to tie the customer to the supplier electronically in order to increase market share and profits. This new tool which goes by the name of Electronic Data Interchange, and is moving rapidly across the entire spectrum of finance in industries. E.D.I. is being used by many companies as a marketing tool for everything from selling plastics to mortgage servicing business. After a business has automated its internal systems, the next question is always how do you move the information it generates to another company. Today about 70% of the Fortune 500 companies are using E.D.I., both on the buy and on the sell side. People have joined networks, which are basically electronic mailboxes so they can send documents anywhere in the world. The © 2008 Digital Collections and Archives, Tufts University 4 © 2008 Digital Collections and Archives, Tufts University drug business has been particularly active in this regard, and it is estimated that in the wholesale drug industry customers transmit 95% of their purchase orders to manufacturers via E.D.I. The major automobile makers all use it and, according to press reports, IBM is seeking to connect two thousand of its largest suppliers right after the turn of the decade. Now whenever you connect directly your business with another one, it changes your relationship. Assuming that the technology works, it becomes easier for your vendors and customers to do business with you in a cost-effective way and much harder for them to deal with others. All of this is now and can be integrated with the manufacturing process so that just-in-time inventory is tied directly to E.D.I. and their vendors. Indeed, all of this is happening at this moment. As the next iteration of technology moves through the business community, even more changes will occur. We have moved in three decades from main frames and batch processing to personal computers and on-line fault tolerant non-stop systems. Today will see much more use of risk technology, of integrated networks, and the increased use of expert systems for everything from medical education to credit scoring. And not only that the end is no where near in sight. We have only just begun where probably only 20% into the productivity revolution created by the computer. But the users are beginning to drive the computer makers now toward open standards, although this process has a long way to go. But if you believe, as I do, that today really is different from yesterday, then these new realities require that we think anew about many of the old business and marketing concepts that used to serve us well in the past, but may no longer be relevant to tomorrow's business world. I think a clear-eyed view of the world would reveal that the old industrial age is fading and is being replaced by the information society. Now this transition does not mean that manufacturing doesn’t matter, or that it’s not important, or that it will disappear, any more than the advent of the industrial age meant that agriculture disappeared. What it does mean is that like agriculture today, manufacturing will produce more goods for more people with less direct labor. It also means that the relative importance -- the relative importance of intellectual capital invested in software and systems will increase in relationship to the capital invested in a physical plant and equipment. The traditional accounting methods designed for another age are, I believe, no longer reflective of what is really happening in the business or in our national economies. Many of the words which we use today to describe our business and our markets flow from business, accounting, and political systems which have grown up over the years. While these words and these systems have served us reasonably well in the past, it can be argued that the numbers produced by our current accounting methodology no longer reflect what is happening in the real world. Everybody knows, for example, that all the lights would go out, that all the airplanes would stop flying, and that all financial institutions would shut down if the software that runs their systems was suddenly to disappear. And yet, these crucial assets that really makes the world go, which are essential for the whole operation of our societies, do not appear in any substantial way on the balance sheets of the corporations of the world. Balance sheets are full of what in the Industrial Age were called tangible assets -- buildings and machinery -- and our mindset today suggests that to © 2008 Digital Collections and Archives, Tufts University 5 © 2008 Digital Collections and Archives, Tufts University capitalize anything that we can't feel or touch would really be cooking the books. Nevertheless, I suggest to you that as the Industrial Age blends into this new information society, it may be time to rethink not only what constitutes an asset, but also how we manage our institutions to take advantage of this new global marketplace. We see new corporate structures developing to manage new manufacturing methods, new products, new marketing and new delivery systems. Management structures across America are already changing dramatically. The old military model which was a model for business of the hierarchical organization charts is beginning to give way to flatter structures designed for quicker response time to serve a global dynamic market. Layers of management, which used to do nothing but relay information from one layer to another, are beginning to disappear. Business is learning that these positions are no longer needed when information technology allows the rapid transmission of vital information to all levels of management without human intervention. The good news for the Western world is that this kind of development, that free societies not only tolerate but encourage, the sharing of vast data bases--something totalitarian governments cannot tolerate--will give the West a huge competitive advantage in the years ahead. But while you and I, all of us, embrace change as a concept, it is profoundly disturbing to us as individual human beings. Even moving across the street can be upsetting, but the massive changes that are now underway and the way the world works, and consequently, in how business leaders must adapt to survive, can be even more difficult. Over the last few decades, we have had many theories of business management. We have moved from the concept of centralized control to decentralization and in some cases back again; we have pursued excellence; we’ve studied theory Z; we’ve constructed sell, grow and harvest matrices; and even learned to be a one-minute manager. But whatever the popular theory of the moment, the fundamental fact remains that those businesses will survive that make change their partner and use the new information technology to understand their marketplace and serve their customers' needs in a better and more cost-effective way. I suggest to you that since the technology that is driving these changes will neither slow down nor go away, it is up to us to position our business to take advantage of the global market which is developing, before our eyes. Thank you very much. (Applause) Moderator: Thank you. Thank you very much. We have a few minutes for questions and there are cards on each table for you to write your questions down. People from the DMA will be collecting them. (pause) First question is -- what financial services companies are the leaders in technological development? I guess we know one of them. Walter B. Wriston: Well, I think that the ones that are in the consumer business are probably the leaders in the technological development; although it is moving very rapidly now. For example, in cognitive expert systems which say reformat money transfers -© 2008 Digital Collections and Archives, Tufts University 6 © 2008 Digital Collections and Archives, Tufts University who come in all kinds of unformatted ways -- so there are several cognitive systems that work on that. There is in the corporate side -- we have issuants of letters of credit directly to costumers, office and so forth. So generally speaking, I think it’s the larger financial institutions that have had the wherewithal to do the R&D to work on. Moderator: Do you see more American banks expanding globally? Walter B. Wriston: See more what? Moderator: Do you see more American banks expanding globally? Walter B. Wriston: Well, what tomorrow looks like, I don’t know. But I believe what’s going to happen is that the banking business and the financial service business is moving into the arena of a business as opposed to a hobby. And -- (chuckles from audience) the -Jack Welch who's the dynamic chairman of General Electric put together a game plan that said -- for General Electric which has been growing with the GNP since Edison hung up his shoes -- said "I want to be one or two in the marketplace or I don’t want to play." And I think that translating that into the financial service business, and what were talking about is building a franchise, and the franchises that are being built in the consumer business, in the credit card business, in the foreign exchange business, and the merchant banking business or whatever. The companies that build the strong franchises are going to be around until tomorrow as players. The smaller banks will build a local franchise, and I see the large ones building global franchises, and the regionals building regional franchises; but without the franchises neither one of them will be around. So we’re moving in a direction that was really not thought of. Years ago I worked for a fella called George Moore who used to go out and say go out and tell him why Citibank’s money is better than Morgan’s. And I suppose that was the first crude definition of a franchise. (Chuckles from audience) We never did get an answer to that by the way. Moderator: Along the same lines, as a matter of fact, in this week’s "Advertising Age" there’s a front page story regarding Citicorp’s launch of a brand banking marketing strategy for customers. There’s also been a lot of news about Chase doing the same thing by the way. Do you believe brand banking to be successfully offered to consumers nationwide with the rise in interstate banking? Is this a trend that all banks will follow? Walter B. Wriston: Well, that’s a very expensive way to get into the business and some institutions obviously will not be able to go into it; but I believe that brand differentiation is the name of the game. As Ted Levitt says, "There is no such thing as a commodity." And the development of the consumer credit card business was -- just to refresh your memory -- every bank had their own card and Citibank had a thing called the "Everything card." To some directors of a bank out there that asked me to come out, and as I walked home with this guy at midnight. He said "You know the 'Everything card' will never get anywhere, and the reason is that the fellow that handles it was pumping gas in Paolo Albo, California and, if he sees something he doesn’t recognize, he’s going to throw it away." And therefore you have to join Visa or Mastercard, and he was one hundred percent right. So that the individual cards, although they’re a lot of niche players around, © 2008 Digital Collections and Archives, Tufts University 7 © 2008 Digital Collections and Archives, Tufts University went with a differentiated card which was Visa and Mastercard which Dick Cooly started out in the Wells Fargo bank; and that is basically other than niche cards like Troyson and Diners, American Express have really blown away the competition. So, I suspect that’s the way it’s going to go. Moderator: One stop shopping, the financial supermarket how do you feel about the future of that concept? Walter B. Wriston: Well, I think that’s a concept that is beginning after thirty years to attain some reality and you see it. The banks have been inhibited by law from selling insurance and so on, but I suspect that more and more you do have a one-stop financial service; but you also next to that will have boutiques next to the A&P. There is always the deli and so the two are not mutually exclusive. Moderator: How do you feel the Bush administration has handled the Savings and Loan crisis? Do the proposed reforms take aim at the root of the problem. In your view, what’s the future of Savings and Loans? Simple question. Walter B. Wriston: Well, every time a established business refuses to serve a legitimate market need you create a competitor. And the commercial banks refused to finance home buying in America. And, when they did that, they naturally created a competitor and the competitor were the Savings and Loan businesses and they were mostly mom and pop stores. And they hung out a sign and hired Roy Rogers for the opening or whatever. And the management skills that were available and those were not outstanding and that was fine as long as somebody told you what you could pay for your inventory called Regulation Q and what you could charge for your product called usury. And you lived on the spread and happily ever after, but when deregulation came along and you had to actually make a choice about how much your inventory cost and make a choice about what you could sell it for. The management talents were just not up to that problem, it is true in commercial banks too. And so they created this huge problem, I think basically because the lobbies permitted the FDIC to raise the insured amount of deposits up to a hundred thousand dollars. The FDIC was designed to protect small people against bank failures, and the next thing that happened historically was that the FED Mr. Blocker elected to save the bond holders of the Continental Annoy which I think was a desperate mistake -- why should we save the bond holders for the equity holders. And it was done on the judgment that it might take down the market. That was his judgment. But once you held harmless the investor and you held harmless the management and you held harmless the depositor you no longer had a business -- you had a state bureaucracy -- so that the regulatory process itself was partially responsible for the S&L crisis. And today it is a giant mess, but there is no logical reason for an S&L to exist because the commercial banks woke up about twenty-five years ago and began to give mortgagees. But we created the S&Ls in our commercial banking business by failure to respond to a market. So, it’s going to cost a lot of money and it’s going to get worse before it gets better. Moderator: Apropos of the state of things again, what’s your general view of merger mania is it good, bad, or is it greed? © 2008 Digital Collections and Archives, Tufts University 8 © 2008 Digital Collections and Archives, Tufts University Walter B. Wriston: All of the above. (Chuckles) © 2008 Digital Collections and Archives, Tufts University 9