The Critical-Analytical Approach to Immigration: Foucault on

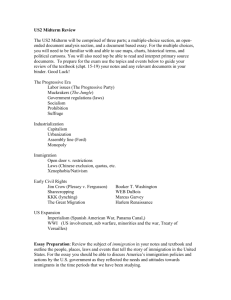

advertisement