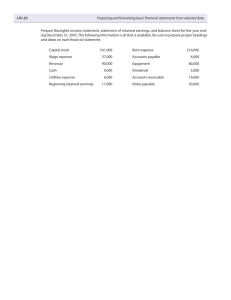

Operating cash flow

advertisement

Heard on the Street Cash Flow? It Isn't Always What It Seems By Henny Sender 1,202 words 8 May 2002 The Wall Street Journal C1 English (Copyright (c) 2002, Dow Jones & Company, Inc.) Cash may be king, but some princely sums reported in financial filings are less than they appear at first blush. Long viewed as the most reliable, least manipulated of the financial documents filed by a company, the "statement of cash flows" has its shortcomings, too, as Dynegy Inc. investors recently learned. Over the years, investors have come to view the section of the statement dubbed "cash flow from operating activities" as a source of important insights into a company's core business, while the document's other two sections -- one tracing cash flow from financing activities, the other tracking investments -- provide other key data about how the company is run. But late last month, the energy-services firm said that, after discussion with the Securities and Exchange Commission, it would revise its cash-flow statement for 2001 so that $300 million tied to a complex natural-gas trading arrangement would be removed from the operating cash-flow section and put into the financing section. While the restatement doesn't change Dynegy's net income, cash flow from operations drops by 37% as a result. Perhaps more importantly, the restatement is a big blow to the many investors who held on to the cash-flow statement as a beacon of truth even as their faith in earnings figures was shattered in recent months by everything from debate over the proliferation of pro forma earnings to an explosion of purported one-time charges they are told to ignore to the collapse of Enron Corp. amid myriad alleged accounting irregularities. "If you think operating cash flow as reported actually gives you operating cash flow, you are kidding yourself," says Trevor Harris, accounting analyst for Morgan Stanley & Co. There is little question: Few things matter more than how much cash is flowing into and out of a company. If a company's core operations aren't generating enough cash, investors can anticipate that the company sooner or later will need to turn to the markets for more funds. The company will load up on either debt (payment of which reduces earnings) or equity (which involves undesirable dilution). Unfortunately, accounting rules give companies plenty of flexibility in what they include in operating cash flow and in classifying cash flows into the operating, investing or financing categories, according to Charles Mulford, accounting professor at Georgia Institute of Technology and co-author of the recently published "The Financial Numbers Game." In the Dynegy instance, the SEC is looking into various aspects of the accounting for the multiyear natural-gas trading arrangement. But Mr. Mulford has compiled a list of the various ways companies can alter operating cash flow to boost results, all within the rules. One common device to make cash flows look better than they would otherwise be is for companies to sell or securitize receivables, Mr. Mulford notes. This practice is now so widespread that almost every company does it, according to Pat McConnell, an accounting specialist at Bear Stearns & Co. But by so doing, "companies are sacrificing future operating cash flows for a one-time boost in these flows," Mr. Mulford says. Consider TRW Inc. Earnings dropped to $68 million in 2001 from $438 million the previous year. Operating cash flow, though, went in the opposite direction; it rose to $1.49 billion from $1.15 billion. The improvement was largely due to $327 million the company gained by securitizing receivables. A company spokesman says that, in notes accompanying its financial statements, the company made clear that the securitization helped operating cash flow. Meanwhile, Lear Corp.'s net income fell to $26 million in 2001 from $275 million in 2000. At the same time, operating cash flow fell to $569 million from $753 million because the company declined to include a sale of receivables that generated cash flows of $261 million. "Sales of receivables and operating cash flows are entirely separate events," says David Wajsgras, Lear's chief financial officer. "We see sales of receivables as a low-cost financing method; it shouldn't generate operating cash flow." Investors should also ask themselves if an increase in operating cash flow is the result of items that aren't likely to recur in the future -- and hence should be discounted. For example, the rules require companies to record tax benefits from exercising employee stock options as part of operating cash flow. Yet these benefits depend on how many people choose to exercise their options and what the stock price is at the time -- variables over which management has limited influence. That, in turn, raises questions about the sustainability of these cash flows. Consider the recent experience of Cisco Systems Inc. In the fiscal year ended July 29, 2000, almost $2.5 billion of the $6.14 billion in net cash provided by operating activities came from the tax benefits of employee stock options. A Cisco spokeswoman acknowledges the role played by tax benefits in the 2000 fiscal year, but notes that by the third quarter of fiscal 2001, the tax benefits became "much less," because employees exercise them at their own discretion. Companies also can adjust operating cash flow upward by taking longer to pay their vendors, thereby increasing their accounts payable, Mr. Mulford notes. For example, at AMR Corp., the parent company of American Airlines, accounts payable increased just over 40% in 2001, to $1.78 billion from $1.27 billion in 2000, providing operating cash flow of $517 million, Mr. Mulford notes. The increase in accounts payable made a precious contribution since overall operating cash flow was down sharply in 2001 -- declining to $511 million from $3.14 billion in 2000. A company spokesman says that $350 million of the $517 million came about as a deferral of U.S. transportation taxes and the remaining $200 million from the acquisition of the assets of TWA. An increase in accounts payable also helped Tower Automotive Inc. in a difficult 2001; the company lost $268 million from continuing operations last year, after making $16 million the previous year. But operating cash flow looked far better in 2001, up to $514 million from $93 million in 2000, helped by a rise in accounts payable to $369 million from $248 million the year before. Like American, "Tower was taking longer to pay in a difficult year," says Mr. Mulford. Tower executives declined to comment, as the company is in a quiet period before a stock offering. But in its most recent annual report, the company said it was seeking longer terms from vendors to improve its management of working capital. If a company isn't growing, negative cash flow can signal unsustainable cash burn. But don't always assume that negative cash flow is a bad thing. In fact, it can signal valuable investment in growth. For example, over many years, Wal-Mart Stores Inc. has produced negative cash flows, according to Mr. Harris of Morgan Stanley, while retailing rival Kmart Corp. has had positive cash flows. But Wal-Mart was investing heavily in its business, and Kmart, which recently filed for Chapter 11 protection under the bankruptcy code, wasn't.