Preface - Coptic Orthodox teaching

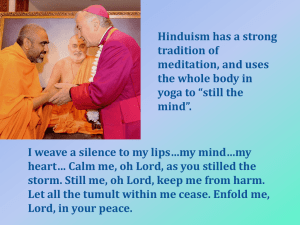

advertisement