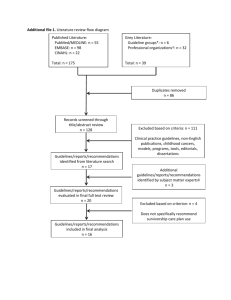

1 - Canadian Association of Provincial Cancer Agencies

advertisement