study guidelines

advertisement

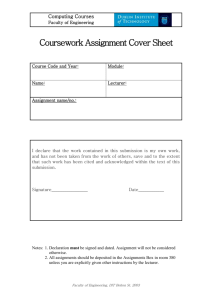

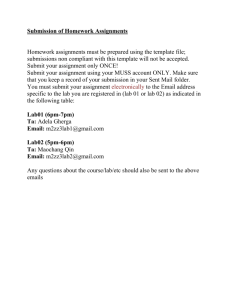

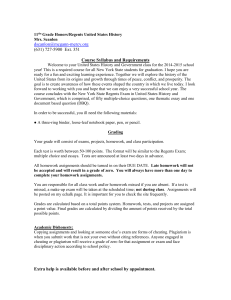

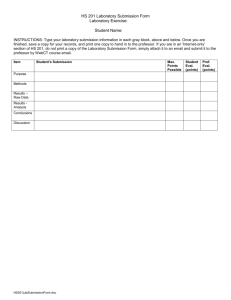

C 2004/737 O N T E N T Study Guidelines 1 Making the Transition to Tertiary Study 3 Developing Effective Study Habits 5 Finding and Using Literature 7 Effective use of Class Time 11 On-Line Learning 19 Preparing for Examinations 21 Assignment Writing 24 Submission Requirements 32 Cheating and Plagiarism 36 Oral Presentations 38 Journaling 40 Conclusion 42 S 1 Study Guidelines STUDY GUIDELINES Introduction Whether you are a school leaver, or a mature-aged student returning to study after a long period, the prospect of studying at tertiary level can be quite daunting. It may take some time to adjust to the norms and culture of university life, as you attempt to balance study along with work and personal commitments. We believe, however, that studying is a positive and enjoyable experience, however challenging and demanding it may seem at times. This guide has been produced by the School of Nursing in conjunction with the Language and Learning Service Unit to assist students to develop skills necessary for studying in the tertiary context. The information provided will prove valuable to both on-campus and off-campus (distributed learning) students. How to use this guide As both student needs and subject requirements vary considerably, these guidelines are intended as an introduction to study skills generally. There is no value in attempting to memorise every section of this guide, familiarise yourself with the contents and then focus on those areas that are important to you. Use it as a reference manual when you need direction in specific areas. You may wish to pay particular attention to the sections relating to Submission of Written Work as these contain policies regarding submission procedures and penalties for late submission. There are a number of additional texts which may be of assistance to you if you feel you require further assistance. Suggested further reading is included at the end of this guide. Students are also encouraged to access the on-line student resource centre, developed by the Language and Learning Services Unit. This site contains a number of resources, including on-line tutorials and access to assistance for both on- and off-campus students. This site can be accessed at: www.monash.edu.au/lls/sif If you have specific concerns, you may wish to contact your Course or Unit Coordinator directly. Please note that these Guidelines should be read in conjunction with the School of Nursing Student Assessment Policy and Referencing Guidelines to ensure a comprehensive understanding of the contents. The following page has been left blank 2 Study Guidelines 3 Making the Transition to Tertiary Study MAKING THE TRANSITION TO TERTIARY STUDY Many students have difficulty making the transition to studying at tertiary level. This is true for both the school leaver and the mature age student who is returning to study after a long break. Often students base their expectations of university on their experiences as a secondary school student. The following list is included to show you how study patterns in university differ from those in secondary school: Secondary Study Tertiary Study 1. The timetable accounts for every hour of the school day. Lectures and tutorials take up part of the day. You must plan you own long- and short-term timetables. 2. Two hours of schoolwork require about one hour of homework. For every one-hour lecture or tutorial, about two hours of private study will be necessary 3. Teachers set and correct your homework frequently (daily, weekly). Assignments are longer but less frequent. They may be set many weeks ahead. 4. You have daily interaction with teachers. Lecture groups may be large. It is up to you to approach your lecturer or tutor if you are having difficulties. 5. Teachers guide your reading. Set texts are prescribed for each subject. You may be given a reading list from which you select, or you may have to search for relevant material in the library. Reading only the set texts is often enough for essay preparation. Wide reading is essential. 6. Teachers may provide outline notes and will indicate the most important ideas and information. You will have to identify and make notes on the main points in lectures and texts. 7. In essays, you refer to the set texts, but need not acknowledge all the sources of your ideas and information. You must acknowledge all your sources. To avoid plagiarism, you will need to learn referencing skills. 4 Making the Transition to Tertiary Study 8. Secondary Study Tertiary Study You learn a core of knowledge and reproduce it in your reports, essays and examinations. You are expected to develop your powers of independent thinking. Developing Effective Study Habits 5 DEVELOPING EFFECTIVE STUDY HABITS Study requires an act of will which rarely comes easily. It is a skill which is gradually developed over a period of months or years. There is no shortcut to success, nor is there one perfect method. The process of acquiring and retaining new information is a very personal thing. While developing effective study habits may involve some degree of trial and error, the following guidelines will assist you in developing a study method that works best for you. Stay motivated Be aware of your goals and be honest with yourself. If you are studying a course without any real enthusiasm, you will need to work even harder to be successful. Remind yourself why you chose to embark on this course in the first place. It is essential that you resolve these matters before you can do justice to yourself and the course. Lack of motivation should be treated seriously. A place apart Set apart a place for study. This should be private, free from noise and other distractions, and it should be comfortable, but not conducive to sleep. Time apart Set apart some time for study. Neglecting to work consistently throughout the year is a reliable method for achieving poor results. It has been tried and tested by many, with the same results – poor marks! The amount of time you need to spend on study will vary from person-to-person. An average full-time student aiming for a pass degree should work a 40-hour week, which includes contact hours and private study. Remember, however, that study is only one part of your life, and it is important to plan for other activities, such as exercise and time with family and friends, to ensure a balanced lifestyle. Devise a study schedule One of the most important factors in developing effective study techniques is the existence of a study schedule. Your study schedule should be tailored to your lifestyle and include personal, work and family commitments. 6 Developing Effective Study Habits A comprehensive study plan includes planning for events across the semester, as well as those that occur on a weekly and daily basis. Once you have received outlines for each subject you should plot out major events for the semester. This includes such things as weddings, birthdays, holidays, etc, as well as dates for assessment requirements for each subject such as assignments, presentations and examinations. Once you have devised your study program for the semester, you can set about preparing a weekly study schedule. Draw up a timetable to assist you in planning your personal study time around scheduled class time and other activities. With each study session, make sure you are organised before you begin. Decide what you are going to study and for how long. In your plan, include some rest periods of approximately 5 to 10 minutes. Work energetically, and if helpful, start off with something you find interesting. Do not avoid the more difficult work, and sometimes expect to struggle to understand some of the work. Most things worth having require effort! Keep up-to-date Keep up-to-date with your study. Review your notes following each class, as this will assist you in retaining information. Revise material regularly throughout the semester, as new topics often require an understanding of earlier work. For this reason it is also important that you seek assistance if you are having difficulties in understanding any subject matter. Get the most out of each study session Do not confuse being “busy” with studying. It is simple to occupy a few hours by rewriting notes, browsing through textbooks, rearranging books and thinking of reasons for studying “later” when the mood is “right”. Study is a disciplined activity which is hard work, but it can be enjoyable. It is important to evaluate regularly whether your study methods are effective. At the end of each class/tutorial try to assess realistically how well you have learnt and understood the work, and plan follow-up sessions accordingly. Identify problem areas early to allow opportunity to discuss concerns with your Unit or Course Coordinator. Don’t be afraid to seek assistance Many factors impact on how well we cope with the demands of tertiary study. Often a little support and guidance can go a long way in helping you to get on the right track. If you find that you are struggling with the course content, or need assistance in developing effective study habits, don’t be afraid to seek help. Contact your Unit or Course Coordinator, or staff from the Language and Learning Services Unit. 7 Finding and Using Literature FINDING AND USING LITERATURE An important skill when studying at tertiary level is the ability to access and utilise literature from a variety of sources. The ability to find and review relevant literature is essential. Most written assignments require you to demonstrate evidence of further reading for a number of reasons: • To establish the current state of knowledge in a given area, or lack thereof. • To compare, contrast or critically analyse existing theories. • To support assertions and arguments made by you. Utilising additional resources is of particular importance for undergraduate students who need to demonstrate ability to acquire knowledge through interpretation of existing literature. Accessing the literature The first stage in developing skills in the effective use of literature is to become familiar with the university library. An academic library differs from a general public library in that it serves many students from a variety of disciplines. It, therefore, covers a wide range of subjects in considerable depth. Whether you are studying on- or off-campus, it is important that you get to know your library and the resources and services that it provides. Library resources As an academic facility, the library at Monash University has an extensive range of resources and services, including: • • • • • academic texts; journals, periodicals and magazines; audiovisual materials; reference and reserve materials; and past exam papers. You can search for specific titles, authors, or general subject headings to locate these items through the Voyager catalogue. Voyager can be accessed in the library or through the library home page (see below). If the item you require is not held by the Monash library, a copy may be obtained for you. Contact the information desk and ask for details about Document Delivery. 8 Finding and Using Literature On-line services A range of library services are available through the Internet. These include: • Access to the Voyager catalogue. • A description of library services. • Databases, some of which contain full-text articles from journals, newspapers, etc. • Email help services. Please note that some of the above services require password access. Please contact the library via one of the means below, or refer to the library guide issued to you on enrolment, if you require further information. You can visit the Monash University Library website at: http://www.lib.monash.edu.au/ Off-campus (distributed learning) students Students enrolled off-campus can access library services via the Flexible Library Services Unit (FLISU). These services include: • • • • • Postal loans. Borrowing in person. Photocopying and fax services. Information search service. Reciprocal borrowing privileges. Further information on FLISU services can be found in your Flexible Library Services booklet, or by visiting their Website at: http://www.lib.monash.edu.au/flisu/ Obtaining assistance Students requiring further assistance in accessing library facilities can contact the library directly by one of the following means: On-campus students By mail: Monash University Library Gippsland Campus CHURCHILL Vic 3842 Telephone: (03) 5122 6423 or (03) 9902 6423 Off-campus students By mail: Flexible Library Services Unit Monash University Library Gippsland Campus CHURCHILL Vic 3842 9 Finding and Using Literature Telephone: (03) 5122 6313 or (03) 9902 6313 Fax: (03) 5122 6882 or (03) 9902 6882 Email: flisu@lib.monash.edu.au Efficient reading strategies When studying, a considerable amount of time is invested in reading. It is, therefore, important that you develop skills in effective reading strategies to ensure efficient use of valuable study time. The following reading techniques are useful when reading for the purposes of study: • • • • Skimming. Scanning. Detailed reading. Revision reading. The key to getting what you want out of your reading is adapting your technique to the purpose. Skimming Sometimes you need to get the general idea or gist of a text. The way to do this is not by reading every word. Few textbooks were written with your specific course in mind. So you need to adapt the material to your particular purposes, given the course and the task at hand. Skimming is the sort of reading which would be appropriate if your tutor asked you to read several books and articles for the next tutorial. He or she would not expect you to be able to recite each word for word, but would want you to be able to discuss the issues raised. You might try reading quickly through the table of contents, the preface and the index, then selecting from the chapter headings. You can then read the first and last paragraphs, and perhaps the first sentence of each of the other paragraphs. Don’t forget to check any diagrams and figures. You should get about 50% of the meaning from all this and you are then in a good position to see if you need to employ scanning or detailed reading. Scanning You skim read material to get the general picture. To find out precise information you will need to practice the technique of scanning. You may need to find out specific details of a topic for an assignment or a task that your lecturer has set. There is little point in skimming a whole book for this purpose. You should identify a few key expressions which will alert you to the fact that your subject is being covered. You can then run your eyes down the page looking for these expressions – in chapter headings or sub-headings, or in the text itself. Detailed reading Some subjects such as law and literature, for example, require a very detailed understanding from the student. This kind of reading is always more time consuming, but can be combined with skimming and scanning for greater efficiency. If it is a photocopy or your own book, take full advantage by 10 Finding and Using Literature underlining or highlighting and using the margins for your own comments or questions. Revision reading This involves reading rapidly through material with which you are already familiar, in order to confirm knowledge and understanding. Maybe summarise main points on to small system cards (these can be bought at any newsagent’s and then be carried around). Reading and note taking Taking notes when reading ensures organisation of information for recall in preparation of assignments, essays or reports, or to prepare for examinations, seminar presentations, etc. As with reading strategies, the nature of your notes when reading is determined by your specific purpose. Whichever approach you use, keep the following points in mind: • Keep your notes brief and to the point. • Write down the information in your own words (if noting down a quotation, be sure to record exact words, punctuation and page number). • Organise information into a hierarchy – decide which are the major points and sub-points. • Pay attention to any definitions and key words or jargon (use a dictionary if necessary). • Always record the full publication details for later referral to the source. You may also wish to indicate page numbers to facilitate future access of any information. 11 Effective Use of Class Time EFFECTIVE USE OF CLASS TIME Over the course of your studies you will be exposed to a variety of instructional methods designed to provide you with new knowledge and skills. The most common methods of instruction in tertiary education are the lecture and the tutorial. Getting the most out of lectures Lectures are traditionally information giving sessions. The lecture is designed to provide large volumes of information to large numbers of students in a short period of time. Preparing for the lecture Prepare for each lecture by reviewing the following: Course outline Reviewing the course outline places the lecture in the context of the whole subject and will indicate which readings relate to the subject matter covered during the lecture. Assigned readings Read, or at least skim, the assigned readings before the lecture. This helps you to get an idea of the content and key issues of the lecture. Previous lecture notes Reviewing notes from previous lectures before each lecture provides context and continuity. During the lecture Your position in the lecture theatre Don’t be frightened of the lecturer, sit close to the front. You will hear and see better, and are more likely to find yourself in the company of committed students. Think more, write less A lecture is not a dictation exercise. You need to listen and make your own judgments about what you should write down. It is not possible to record every word that the lecturer says; you simply cannot write as fast as they speak. Nor is it a good idea to try. Writing down every bit of information will obscure the most important points. Also, you are likely to miss important information because you are concentrating on copying down what was said previously. 12 Effective Use of Class time Therefore, you should try to discriminate between what constitutes the main points of the discussion and what is supporting information. Listen for structural cues In order to effectively identify the important points of a lecture, you should attempt to listen actively for structure and argument; don’t just take notes passively. Listen for signalling words which indicate the parts of a lecture: • Words such as first, second, also, furthermore, moreover, therefore and finally indicate stages in the lecturer’s argument • But and however indicate a qualification, because a reason, and on the one hand and on the other hand indicate a contrast. Certain phrases also suggest the structure of a lecture: Introducing the lecture: “I want to start by …” Introduction of a main point: “The next point is crucial” Rephrasing the main point: “The point I am making …” Introducing an example: “Take the case of …” Moving on to another main point: “I’d like to move on and look at…” A digression: “That reminds me of ….” Summing up main points: “To recapitulate….” Organise your notes Head notes clearly with the date, lecturer’s name, topic and number in lecture series. Number and identify subsequent pages. Impose a hierarchical structure of main points and supporting information or facts: I. Major Heading A. Sub-heading (details) B. Sub-heading (details) II. and so on… Use capital letters, underlining and/or indenting from the margin to differentiate major and minor points. Often it is difficult during the lecture itself to identify the main points and sub-points. It is therefore important to organise your notes into a hierarchy as soon as possible after the class. 13 Effective Use of Class Time Note key phrases and use abbreviations Don’t take down complete sentences, use key phrases. If the lecturer is going too quickly, leave plenty of space and get the information later from the lecturer or friends. 14 Effective Use of Class time Write clearly and use space wisely to make your notes easy to read and assimilate. Have wide margins, etc, to leave room for later comments. Use your own words as much as possible as this will make you think about the material and increase your understanding of it. Use abbreviations, but ensure that you will be able to understand them later. The following is a list of abbreviations and symbols that you may be able to incorporate into your lecture notes: Arrows Common Abbreviations an increase c with a decrease w which causes/leads to/results in e.g. for example is caused by/is the result of re concerning is related to ca about Mathematical symbols A.M. morning therefore P.M. afternoon because etc and so on = is the same as N.B. note well is not the same as 18 18th Century is greater than b/f before is less than cf compared with % percent viz namely + and q.v. refer to, see ® right et al. and others left i.e. that is pa per annum, each year L Emphasise Shorten suffixes Underline Capitalise Highlight n tion/sion g ing -to show what is important 15 Effective Use of Class Time After the lecture Re-read your notes as soon as possible after the lecture, while your memory is still fresh. At this time it is a good idea to edit, understand, summarise and add. • Edit your notes to make sure that your writing is clear and you can recognise abbreviations. Fill in any gaps by adding additional information you recall or expanding any points that are sketchy. • Make sure that you understand everything in the lecture. If you need clarification seek assistance as soon as possible from the lecturer or your friends. • Summarise the main points in your own words. • Add ideas, comments or questions. Reviewing your notes regularly throughout the semester consolidates your learning and prevents the need for last minute cramming before examinations. Participating in tutorials Tutorials are often used to permit discussion or elaboration of material presented during a lecture, or to present new information which requires a greater level of instructor/student interaction. Tutorials are generally conducted in smaller groups than lectures to facilitate greater student participation and group discussion. Attendance • Regular attendance is advisable. Be aware that for many subjects attendance is compulsory. Interaction • Participation in discussion is important in tutorials and seminars. • You may be expected to reflect on the topic and to examine it critically. This involves saying what you think about the points being discussed as well as giving reasons for your position. Preparation • Do any set pre-reading to become familiar with the topic. • Attempt the tutorial problems before the tutorial so that you are able to participate and can ask questions about areas you don’t understand well. • Consider how the current week’s material fits in with the previous weeks, and the overall subject. Participation – some hints • Think of several questions/comments you would like to make. Form them into sentences, practice them in your head and out loud. 16 Effective Use of Class time • Be ready in the tutorial to make your comment. Look for pauses to enable you to enter the discussion. • Indicate that you want to speak by making eye contact with the tutor or taking a more alert body posture. • Be prepared to feel nervous with your first few contributions. (You are not alone!) After the tutorial • • • • • Contact your tutor to clarify any important points you didn’t understand. Finish any unfinished work. Revise – sit down and consolidate what you have learned (concepts). Enter questions in your notebook; write answers. Check terms/jargon. The following page has been left blank Effective Use of Class Time 17 19 On-Line Learning ON-LINE LEARNING On-line educational software programs provide you with a range of interesting learning activities. Many units available through the School of Nursing use the WebCT system. In addition to the activities conducted in class, and outlined in off-campus learning materials, you will also have access to on-line tutorials, glossaries, FAQ files, discussion groups and other resources to assist in your study. To access the WebCT site for a unit in which you are enrolled, you will need to carry out the following steps. Step 1 As a Monash University student you will have an AUTHCATE user name and password to access the library and other Monash University on-line resources. You will use this to gain access to WebCT. Only students enrolled in a unit with a WebCT component will have access to this site. Make sure you have a valid AUTHCATE username and password. Step 2 To access WebCT you will need to type the following URL into your Netscape Navigator or Internet Explorer web browser. The URL is http://webct.monash.edu.au Entering this URL will bring up the “WebCT Welcoming Page”. Click on “Log onto my WebCT”. Step 3 The “Login to WebCT” screen will appear. Enter your AUTHCATE username and password. Click the “Log in” button. Step 4 If log in is successful you will now be presented with your own MyWebCT page. At the top of the page will be MyWebCT: (your name). Under the courses column on the left-hand side of the page will be a list of any units that you are enrolled in that use the WebCT system. Click on any unit icon to be taken to the Home Page for that unit. 20 On-Line Learning You can now navigate around the web site using the icons and WebCT’s other navigation tools. Step 5 If you have problems logging onto or using WebCT, access the WebCT help desk at: http://www.celts.monash.edu.au/html/helpdesk_for_webct.html Should you continue to experience difficulties, contact your local Course Administrator or Unit Coordinator for assistance. 21 Preparing for Examinations PREPARING FOR EXAMINATIONS Most students find formal examinations a daunting experience. The secret to overcoming exam anxiety lies mainly in being as prepared as possible. The following guidelines are provided to help you be your best before, during and after an examination. Before the exam Develop regular study habits Cramming at the last minute is the least effective method of studying for an examination. Regular (daily) consolidation of information is essential to ensure that you possess an understanding of subject matter, and are able to retain key information. Studying throughout the semester ensures that you will have time to access lecturers or additional resources if necessary. While you will obviously increase your study load prior to an exam, relying on this method solely will reflect in your performance. Find out what format the exam will take Your lecturer may give you guidance as to the basic format of the examination. Don’t be afraid to ask whether to expect multiple choice, short answer or essay type questions. This is dictated, to some extent, by the nature of the subject matter to be covered. Reviewing former exam papers can also be useful in knowing what to expect. Know the subject matter to be covered Subject outlines generally provide guidance as to the nature of the subject matter to be covered. For many subjects, all material covered over the semester will be contained in the exam. If unsure, ask the unit coordinator. Stay healthy It is easy to fall into the trap of becoming totally absorbed in study during exam time. Usual routines fall apart as priorities shift. Where possible, you should endeavour to eat properly and get some exercise to minimise stress and to prevent you from succumbing to illness because of diminished defences. During the exam Stay calm This is much easier said than done! Take a deep breath and try to relax. Avoid panic, this will only make things seem worse than they are, and will affect your concentration and ultimately your performance. 22 Preparing for Examinations Listen to instructions Follow the instructions given at the commencement of the examination. Failing to complete your details correctly or writing before official commencement of the exam can rattle your concentration. Make the most of reading time Reading time is designed to give you opportunity to clarify any points of concern and clear up any inconsistencies. Read the questions thoroughly, but don’t waste too much time as time provided for preliminary reading is usually minimal. Don’t be afraid to ask questions following reading time. Read the questions properly An unfortunate, yet common cause of lost marks in examinations is a result of the student failing to read the question properly. Many students anticipate a certain type of question and subsequently mis-read similar questions. Read each question at least twice before attempting it. Underline key words within the question, especially words that direct your response, such as outline, describe, discuss, etc. Before you attempt to answer a question, you should also check the number of marks that your response is worth. This will give you some idea of the extent of the response required, and the amount of effort you should devote to it. Write as concisely as possible Don’t try to impress your examiner with lengthy responses. Be sure to remain concise and to the point. Often students who aren’t sure of the answer try to write down everything they know about a topic in the hope that they might get something right. Often, however, it can alert the examiner to the student’s deficiencies in an area and can prove a waste of valuable time. Always answer the questions you are confident about first, and those that represent the greatest points value. Don’t be afraid to use diagrams, charts, etc, to illustrate your point. Often a picture can paint a thousand words, especially when used to describe complex processes or relationships. Re-read your paper If time permits re-read your paper to make sure your responses are clear and to check that you haven’t missed any questions. If you are tempted to change a response think seriously about whether it is the best course of action. Make sure also that you have clearly recorded your name and student number, and any other information requested, appropriately. After the exam Don’t pre-empt the results Examination post-mortems are inevitable – some people thrive on them! Try not to dwell on your performance, however, as it will only serve to affect your mood rather than your results. This is especially important if you have to prepare for examinations in other subjects. Preparing for Examinations 23 24 Assignment Writing ASSIGNMENT WRITING Writing assignments, including essays, is a significant means of communicating your ideas, thoughts and arguments, well supported by the writing of others. While written assignments are a form of self expression which reflect your own style, they are a major means of demonstrating your knowledge and understanding of the concepts, notions and issues contained in your study program. Thus your lecturers can assess your ability to think reflectively and critically about the topic. The following guide to assignment writing has been prepared with the aim of providing a simple, easy-to-follow approach to assignment preparation and writing. Essay writing does take time and effort. This guide, therefore, has been prepared with the intention of making your time spent as productive as possible. Stages in assignment writing Preparation • • • • Define the topic. Brainstorm. Collect information. Prepare an outline. Organisation • • • • Pause and consider the topic. Select and order information. Prepare a detailed plan. Prepare the first draft. Presentation • • • • • • • Edit the first draft. Sort paragraphs. Write introduction and conclusion. Check grammar, spelling and punctuation. Complete referencing. Write the final copy. Check the final copy. Preparation Defining the topic Understanding and defining the topic or question asked is the first hurdle to overcome in assignment preparation. It is important that you correctly interpret the question, in order to present the required information. 25 Assignment Writing The actual essay question needs to be clearly understood. This involves identifying the verb, eg. compare or discuss, in order to determine the type of information that needs to be presented. To help you, some common assignment terminology has been included. Analyse Separate a complex idea or argument into its smaller parts. Comment Make critical observation, using your knowledge of the topic. Compare Requires examination of the subject and demonstration of the similarities and differences between two or more ideas, or interpretations. Criticise Express your judgement regarding the correctness or merit of the factors being considered. Discuss the strengths and weaknesses, giving results in your analysis. Define Provide concise, clear, authoritative meanings. Describe Provide an account of an event or process, emphasising the important points. Discuss Look at all aspects of the issue; debate the issue, giving your reasons for and against the argument being proposed. Your opinion must be supported by authoritative evidence. Evaluate Appraise, assess and make a judgement, stressing both strengths and weaknesses, advantages and disadvantages. Explain Make the meaning clear but do not be trapped into describing or summarising events. Focus on the “why” or “how” of the issue. Illustrate Using figures, diagrams or concrete examples, explain or clarify an idea or concept. Outline Write an organised description of the essential parts, omitting the minor details. Any technical terminology in the assignment question also needs to be identified and understood. If you have any problems at this stage of preparation, you may seek advice from your Unit Coordinator. 26 Assignment Writing Brainstorming Following clarification of the terminology, the technique of brainstorming the essay question can be used. Brainstorming is the process of writing down any spontaneous ideas regarding the essay topic, without pausing to consider whether the material is appropriate or useful. This approach takes little time and is a useful technique to focus your thoughts on the assignment topic. Information collection Collection of information is the next important component of the preparation stage. The search for reference material and reading should begin as early as possible, to introduce you to the topic. This may appear daunting at first. However, browsing through the literature and using the library’s computer database and CD ROM facilities to identify the relevant sections and articles will simplify the task. You may wish to refer back to the previous section on Finding and Using Literature. Outline When you have collected the required information the last part of the preparation stage is devoted to preparing a brief outline of your assignment. A flow chart may be used, ie. a point form summary of ideas linked together by arrows. The need to organise your ideas and information is an important step in the planning of your assignment. Organisation During the preparation stage, you determine the information and evidence that is relevant to your topic. The actual organisation of your material should flow on smoothly from this stage. Pausing between information collection and the actual writing of your assignment will help you to organise your ideas and the information that you have obtained from your reading. Ordering of information is a technique which some people find difficult; there are no set rules. Material may be ordered in a variety of styles. Refer back to the assignment topic as the order may be suggested by the question. In some situations it may be up to you to experiment and develop your own style. Use the flow chart or outline that you developed during the preparation stage to prepare a detailed plan of your essay. The key to planning lies in relating the various parts of your reading and thinking to the topic. Your argument is essentially the linking together of other peoples’ ideas with your own and relating them to the topic. Remember that your own ideas regarding the topic are an important part of your assignment, however they may need to be substantiated by the ideas of other authors. In some cases you may need to evaluate competing ideas. In this situation you are able to express your opinion of why one argument may be better than the other. However, your argument should be supported with reasons and evidence obtained from the literature. 27 Assignment Writing Draft writing At this point you begin to write your assignment, remembering to base it on the plan that you have prepared. A draft is written so that you are later able to revise your argument where necessary. It is often useful to leave a day or two before rereading or revising your draft. You do not need to write the introduction and conclusion at this stage. Concentrate instead on completing the drafts. Citing your references in an abbreviated form as you write will save time in the final presentation of your assignment. Presentation This stage involves the completion of your essay for submission. The draft is edited, paragraphs sorted, an introduction and conclusion written, grammar, spelling and punctuation checked and the final copy prepared for presentation. Paragraphs Paragraphs should be in a logical sequence, flowing from one to the next. They usually contain one idea and its explanation and should not be cluttered with other ideas and information. Length The prescribed length should be observed. Penalties may be incurred for work which is significantly under or over length. Table of contents When writing in a report format, that is, when headings are present, a table of contents should also be included. This occurs after the title page. Other tables, such as tables of figures, diagrams or plates should follow on directly from it. Introduction The introductory paragraph or paragraphs should refer to the question and provide a map of your intentions or how you will approach the topic. It is an opening into your essay, and therefore should be sharp, interesting and to the point. Conclusion The conclusion summarises your argument and should be a reminder to the reader of the main areas discussed. At this stage do not introduce any idea which you have not discussed previously in your essay. Revision Be sure to check your spelling, grammar and punctuation prior to submitting your assignment. If these areas are poor, then what may have been a high quality assignment, becomes mediocre. It is often helpful to read your assignment aloud, adding the punctuation in the appropriate places as you do so. Referencing Referencing is an important aspect of your assignment. The School of Nursing prefers the APA style of referencing. For a fuller description of this method, refer to the School of Nursing Referencing Guidelines booklet. 28 Assignment Writing A reference list containing publication details of all citations contained within your assignment must accompany your work. You may also need to include a bibliography which lists all resources accessed as background material but not actually referred to in your assignment. Appendices An Appendix is included after the bibliography/reference list and is usually not included in the word limit of an essay. The contents of an appendix is considered to be supplementary in nature to the subject material. All appendices should include full reference details where appropriate, should be labelled alphabetically and have a sub-title. This sub-title should appear in the table of contents. Final copy Your referencing should be rechecked to ensure its accuracy. Once the final copy has been presented, you are responsible for the content and presentation. Always keep a copy of your assignment in case of loss or damage to the original. Assignment presentation guidelines 1. Use A4 paper typed on one side only. 2. Leave a 4 cm margin on the left side of the page with double spacing between lines. 3. Pages should be numbered and stapled together (it is preferable that you do not use plastic pockets, folders, etc). 4. Attach an assignment title page (see example). 5. Attach an assignment cover sheet (as described in the following section). 29 Assignment Writing Assignment title page (example) Lecturer: Unit Code and Name: (For example: NUR2446: Management of Nursing Care) Assignment Number And Title In Full: Student Name: Students No: Due Date: 30 Assignment Writing Academic style As you develop as a tertiary student, you will begin to appreciate the differences between the kind of writing you need to employ for different subjects. You will learn this from the books you read, from the way the lecturers express themselves and from practising writing yourself. An increasing awareness of the characteristics of academic discourse will give your writing greater formality and conciseness. While it is understandable that your writing will, to some extent, reflect your personality, you should bear in mind that a colloquial, informal style is out of place in the tertiary context. Two conventions of academic writing are of particular importance – use of an impersonal style, and non-discriminatory language. Use of an impersonal style In general terms, an impersonal style is preferred. The use of personal pronouns in the presentation of your assignment is therefore inappropriate. For instance; “I will focus on...” becomes “This paper will address....”. Any exceptions to this rule are outlined in individual unit guides. Check with the Unit Coordinator if you require clarification of individual assignment requirements. Non-discriminatory language It is University policy that non-sexist and non-racist language should be used at all times. Non-sexist language refers to language that includes women and treats women and men equally. In avoiding sexist language students should not use language that makes women invisible or dependent, or relies upon trivialisation or stereotyping of women’s lives. Equally, care must be taken to avoid language that trivialises, marginalises, stereotypes or denigrates any race. Grading of assignments Assignments will be graded as follows: High Distinction (HD) Distinction (D) Credit (C) Pass (P) Fail (NN) – – – – – 80% or above 70-79% 60-69% 50-59% Below 50% The following page has been left blank Assignment Writing 31 32 Submission Requirements SUBMISSION REQUIREMENTS On-campus students Submission procedure Due dates for submission of assignments are set to facilitate administration of your course. Assignment submission dates will be posted at the beginning of each semester. You should refer also to the Unit Book for each unit. Assignments must be accompanied by an assignment cover sheet. Individually bar-coded cover sheets for each unit must be obtained from the Monash portal at http://my.monash.edu.au. Please ensure that the type of submission, as described in the Unit materials, is accurately completed to facilitate processing and recording of your assignment. Assignments must be submitted via the assignment boxes at the School of Nursing Office before close of business on the due date. Assignments submitted by mail should be posted to arrive on or before the due date. You are reminded to keep a copy of your assignment in case of loss or damage to the original. The staff in the School of Nursing acknowledge students’ input in their written work. Every effort will be made to return students’ work within four weeks. Students will be notified by the lecturer when circumstances prevent the return of assignment within that time. Extensions Students seeking an extension of time for submitting an assignment are expected to make a written application via email using the Monash University student email service. Students are required to confirm delivery of the email message by requesting a return receipt when sending the email to the relevant staff member. Applications for extension of time must be made to the Unit Coordinator. The Unit Coordinator will then respond to the student via email, granting or denying the extension. Application for extension must be made prior to the due date for lodgement of the assignment. The grounds for granting an extension are similar to those for special consideration. They include health problems, compassionate reasons and other extenuating circumstances. When an extension is granted for an assessment item, the approval email sent by the Unit Coordinator must be attached to the assigned work when it is submitted. Failure to submit an assessment item on time without an approved extension will incur a penalty, as discussed below. Note that an extension may not be given beyond the return date for marked assignments. 33 Submission Requirements Penalties for late submission Penalties for late submission of assignments will be applied in cases where submission of an assignment is not accompanied by an approval of extension email or the granting of special consideration. The penalty will be deducted from the mark for the assignment as follows: Up to one week late More than 1 week but less than two weeks More than two weeks 15% 30% 45% Off-campus (distributed learning) students Submission procedure Australia Due dates for submission of assignments for off-campus units are contained within Unit Guides. The due date requirement is satisfied if the assignment is received by the Centre for Learning & Teaching Support (CeLTS), Monash University (Gippsland Campus) on or before the due date. Every effort will be made to return assignments to students within four weeks after the due date. With your study material you will receive individual bar-coded cover sheets for each assignment to be submitted. Be sure to include your assignment cover sheet with each assignment. The bar-code simplifies its entry into the assignment tracking system. Some students like to photocopy extra cover sheets for use in emergencies. Do not alter the bar-codes in any way. Assignments can be submitted by any of the following means: 1. By post, addressed to: Student Support Unit (SSU) Centre for Learning & Teaching Support (CeLTS) Monash University Gippsland Campus Northways Road CHURCHILL Vic 3842 OR 2. By placing them in the special locker inside the CeLTS office during business hours. OR 3. By placing them in the Monash Gippsland mailbox outside the main entrance after hours. OR 4. By facsimile by dialling (03) 5122 6578 (if you send the original of the fax by mail, please note this clearly on the front of both documents). 34 Submission Requirements The staff of CeLTS will record receipt of your assignments and send them to the Unit Coordinator for marking. If you wish to have receipt of your assignments acknowledged, you can complete the acknowledgement card supplied with your study materials, affix a stamp and submit it with your assignment. This card will be stamped and returned to you by CeLTS on receipt of your assignment. Malaysia Due dates for submission of assignments for off-campus units are contained within Unit Guides. The due date requirement is satisfied if the assignment is submitted on or before the due date. Assignments should be submitted via the MUSO (WebCT) site for the respective Unit. Guidelines for submission of assignments on-line are contained within the Unit materials and/or on the MUSO site for each Unit. Students experiencing difficultly submitting assignments on-line should contact their Unit Coordinator as soon as possible. Every effort will be made to return graded assignments to students within four weeks after the due date. Hong Kong and Singapore Students are required to submit their assignments by the due date indicated in the Unit Guides directly to the organisation through which they are enrolled. Procedure for submission is described in your Student Handbook. Papua New Guinea Students are required to submit their assignments by the due date indicated in the Unit Guides directly to the local facilitator appointed by their host institution. Important: Students are reminded that it is their responsibility to retain a copy of all work submitted. Resubmission may be required in case of loss, or of damage to an original assignment. 35 Submission Requirements Extensions Students seeking an extension of time for submitting an assignment are expected to make a written application via email, letter or fax. Applications for extension of time must be made to the Unit Coordinator via the local Course Administrator. Application for extension must be made prior to the due date for lodgement of the assignment. The grounds for granting an extension are similar to those for special consideration. They include health problems, compassionate reasons and other extenuating circumstances. When an extension is granted for an assignment, evidence of approval (e.g. printed email/fax response) must be attached to the assigned work when it is submitted. Failure to submit an assignment on time without an approved extension will incur a penalty, as discussed below. Note that an extension may not be given beyond the return date for marked assignments. Penalties for late submission Assignments received after the due date may be marked as a ‘fail’, returned without being marked, or receive a penalty unless an extension has been granted. The policy of the School of Nursing regarding penalties for late submission of work submitted in units studied off-campus is as follows: 1. Arrival on or before due date – no penalty. 2. One week (seven days) – non-penalty grace period (To cover postal time particularly in remote areas). Students found to be abusing the grace period may be penalised. 3. 8-10 days late – 10% of assignment value to be deducted. 4. 11-15 days late – 20% of assignment value to be deducted. 5. 16-20 days late – 30% of assignment value to be deducted. 6. 21 days and over – 50% of assignment value to be deducted. For example, if a student submits an assignment which is nine days late and receives a mark of 25/40, a 10% late assignment penalty will mean the student loses four marks off the mark allocated and received a final mark of 21/40 (i.e. 25-4 = 21). 36 Cheating and Plagiarism CHEATING AND PLAGIARISM Students must be aware that cheating and plagiarism are regarded as very serious offences. Where such offences are identified the student is likely to fail the unit concerned and be subject to additional penalties which may include expulsion. The full University policy on cheating and plagiarism is available at: http://www.monash.edu.au/unisec/academicpolicies/policy/plagarism.html In this University, cheating means seeking to obtain an unfair advantage in any examination or in any other written or practical work to be submitted or completed by a student for assessment. Cheating includes the use, or attempted use by or for a student, of any means to gain such unfair advantage in any examination, or for any work, where the means is contrary to the instructions for such examination work. Cheating also includes the taking into an examination of any material other than material approved by the chief examiner of the unit concerned. For the purpose of this section, the expression “any material” shall include any bilingual dictionary. Plagiarism means to take and use another person’s ideas and/or manner of expressing them and to pass them off as one’s own by failing to give appropriate acknowledgement. Hence if the passing off was: • done intentionally, the student has cheated; • not intentional, the only offence the student has committed is the academic misdemeanour of failing to reference a source correctly. There are two main forms of plagiarism: • Copying out passages of another author’s work word-for-word without acknowledging the source. This includes copying another student’s work. • Paraphrasing without citing the source. Paraphrasing is translating the author’s terms or ideas into your own words. This practice is acceptable if enough information is given in the text to identify the work from which the paraphrase originated. The particular book or journal article is then identified in your reference list. Plagiarism may take the form of similar work submitted by students who may have worked together. It is essential that Lecturers provide students with clear instructions as to whether they have been permitted to work on the assignment 37 Cheating and Plagiarism jointly, or individually. The incidence of collaborative work should be made absolutely clear. If there are no substantial factors to indicate that plagiarism was accidental or unintentional, plagiarism – non examination – will be treated as cheating. A member of the teaching staff who has reasonable grounds to believe that nonexamination cheating has occurred, must report the matter to the chief examiner. Where the chief examiner has reasonable grounds to believe that nonexamination cheating has occurred, the chief examiner must: • disallow the work concerned by prohibiting assessment; or • report the matter to the relevant faculty manager. Where a student’s work has been disallowed: • the chief examiner must give written notice of the disallowance to the student and to the associate dean (teaching) of the faculty concerned, including advice that the student may appeal within 28 days of the date of the written notice; and • the student may appeal to the relevant faculty discipline committee. 38 Oral Presentations ORAL PRESENTATIONS One of the most overwhelming experiences for some students can be having to give oral presentations in a tutorial or seminar situation. It is, however, essential that you develop skills in presenting information in this way as it will continue to be an important aspect of your professional development. Becoming skilled in oral presentations will provide you with good grounding for future in-service lectures in your work environment, and for presenting information at conferences and seminars throughout your career. You will find that with practice your skill and confidence level will increase. A little anxiety is quite common, however, and can be beneficial in keeping you on your toes! The following guidelines will help to ensure the success of your presentation: 1. Choose a topic that will be of interest to your audience. 2. If you have a set topic, find an interesting way of focusing your presentation. 3. Try to introduce your talk so that interest is immediately aroused. 4. Establish eye contact with audience. 5. Be responsive to your audience. 6. Avoid reading. Use cue cards. 7. Don’t speak too fast. Speak clearly. 8. Always aim to supplement verbal information with some visual information. 9. Practise beforehand with a classmate or visit the staff at the Language and Learning Services Unit. 10. Start your talk calmly. 11. Introduce the topic and tell the audience what they can expect to hear. 12. Use linking words and phrases to keep your audience informed as to where the talk is heading and how ideas relate to each other. 13. Get your intonation right when emphasising major points, making asides, asking questions and making statements. 14. Control your hands. Do not fiddle with clothing, hair, pencils or papers. 39 Oral Presentations 15. Make sure you do not turn your body or face away from the audience when you are using visual aids. 16. Look pleasant. Stand or sit in a relaxed way. 17. Do not hand out materials while you are actually talking. Wait for materials to be distributed around the room and then resume your talk. 40 Oral Presentations JOURNALING The School of Nursing uses journal keeping as an activity of learning in selected courses and units. Keeping a reflective journal can be a valuable exercise both personally and professionally. Where journaling is a requirement in a course or unit, guidelines for the use and submission of journals will be provided within the relevant Course or Unit Guide. In view of the personal nature of keeping journals, the School of Nursing has developed a code of ethics for personal/professional journals: • The reader will normally be the lecturer coordinating the particular subject or topic. • The reader acknowledges, and is sensitive to, the personally intrusive and insightful nature of reflective journaling. • By submitting a journal, the student has completed a course requirement. The journal itself is not assessed or graded, although reflections from a journal may be integral to a subsequent student assignment. • The assessor shall not knowingly cause psychological distress to the writer nor cause professional disadvantage on the basis of journal content. • The reader is responsible for maintaining security of student material and confidentiality of journal content during the review process. • The reader shall not photocopy or reproduce any journal. • Students submitting personal/professional journals should ensure that individuals and organisations are not identifiable. • The journal remains the personal property of the author. The following page has been left blank Journaling 41 42 Conclusion CONCLUSION Studying at tertiary level can be a rewarding and enjoyable experience. This does not mean to suggest that it won’t be demanding and challenging at times! The key to successful studying is planning, preparation and a positive attitude. You should also remember that when difficulties do arise you are not alone. Talking problems over with friends often helps you to see things in context. Don’t hesitate to contact lecturers within the School of Nursing, and the staff of the Language and Learning Services Unit if you find you need help, or just need to talk things over. Study skills references Barass, R. (2002). Study!: A guide to effective learning, revision, and examination techniques (2nd ed.). London; New York: Routledge. Bernard, G.W. (2003). Studying at university: How to adapt successfully to college life. London; New York: Routledge. Cottrell, S. (2003). The study skills handbook (2nd ed.). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. De Fazio, T. (2002). Studying part time without stress. Crows Nest, NSW: Allen & Unwin. Hamilton, D. (2003). Passing exams: A guide for maximum success and minimum stress. London: Continuum. Hay, I., Dungey, C., & Bochner, D. (2002). Making the grade: A guide to successful communication and study (2nd ed.). Melbourne: Oxford University Press. Lashley, C., & Best, W. (2003). 12 steps to study success. London: Continuum. McIlroy, D. (2003). Studying @ university: How to be a successful student. London: Sage. Pérez, A., & University of Melbourne. Learning Skills Unit. (2002). Studying in Australia: The study abroad student’s guide to success. Melbourne: Learning Skill Unit University of Melbourne. Writing skills references American Psychological Association. (2001). Publication manual of the American Psychological Association (5th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Anderson, J., & Poole, M. E. (2001). Assignment and thesis writing (4th ed.). Milton, Qld.: John Wiley & Sons. Beazley, M. R., & Marr, G. E. (2001). The writers’ handbook (2nd ed.). Albert Park, Vic.: Phoenix Education. Clare, J., & Hamilton, H. (2003). Writing research: Transforming data into text. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone. Coffin, C. (2003). Teaching academic writing: A toolkit for higher education. London: Routledge. Conclusion 43 Cooper, S., & Patton, R. (2003). Writing logically, thinking critically (4th ed.). New York: Longman. Gelfand, H., & Walker, C. J. (2002a). Mastering APA style: Instructor’s resource guide (5th ed.). Washington, D.C.: American Psychological Association. Johnstone, M.-J. (2003). Effective writing for health professionals: A practical guide to getting published. Crows Nest, NSW: Allen & Unwin. Mayfield, M. (2003). Thinking for yourself: Developing critical thinking skills through reading and writing (6th ed.). York, PA: Heinle & Heinle. McLaren, S. (2003). Writing essays and reports. Glebe, NSW: Pascal Press. Smith, P. (2002). Writing an assignment: Effective ways to improve your research and presentation skills (5th, rev. and updated.). Oxford: How To Books. Zilm, G., & Entwistle, C. (2002). The smart way: An introduction to writing for nurses (2nd ed.). Toronto: Elsevier Science.