the landmarks plot

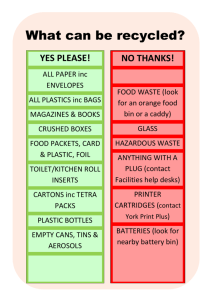

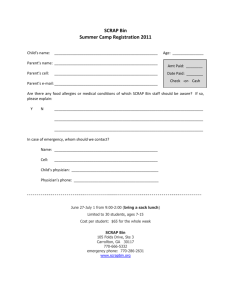

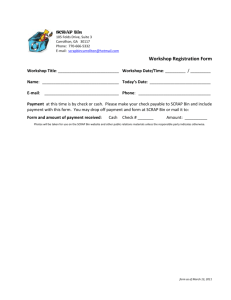

advertisement