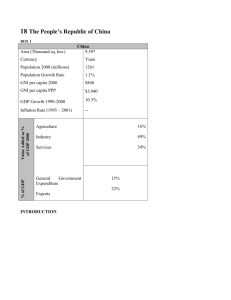

Socialism and the end of the perpetual reform state in China

advertisement