section two: the essentiality of recognition

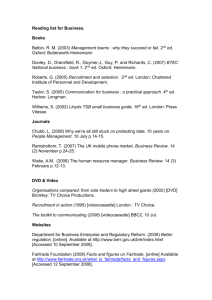

advertisement