Oracle V. Peoplesoft: A Case Study

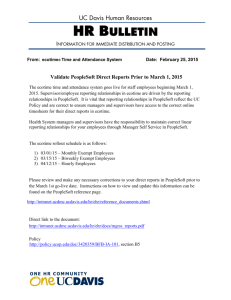

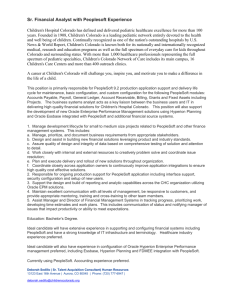

advertisement