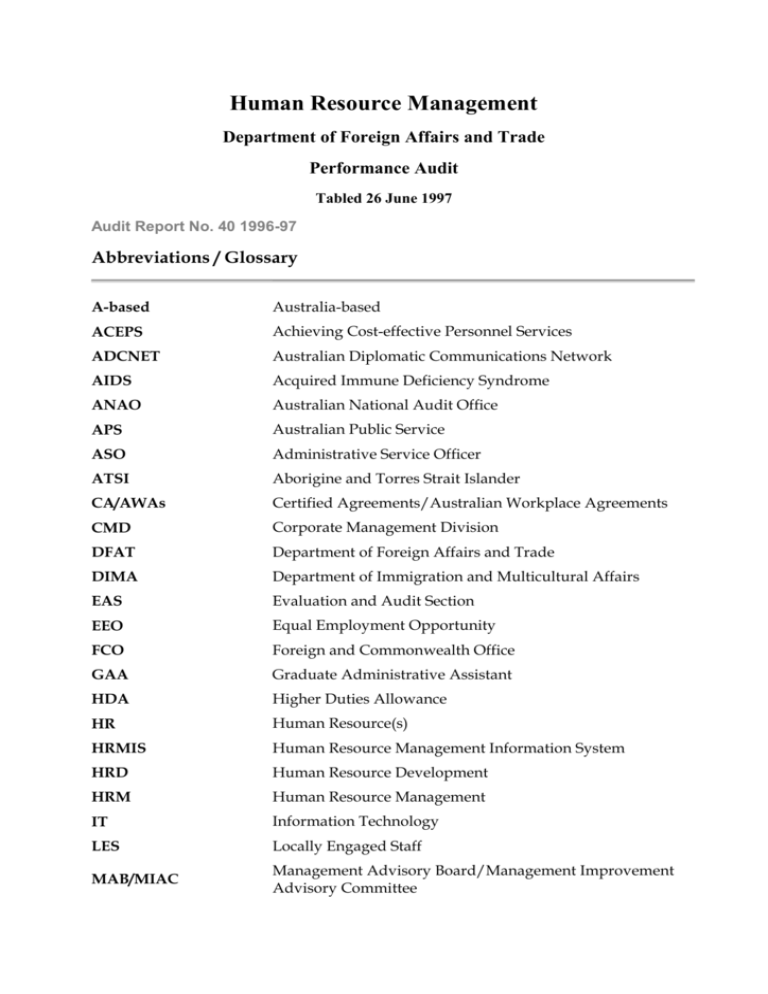

mis reporting proposal - The Australian National Audit Office

advertisement