Property Law - LAWS2204 - ANU Law Students' Society

advertisement

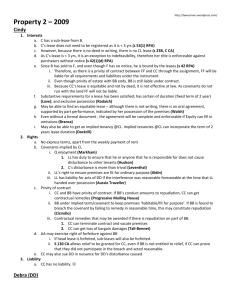

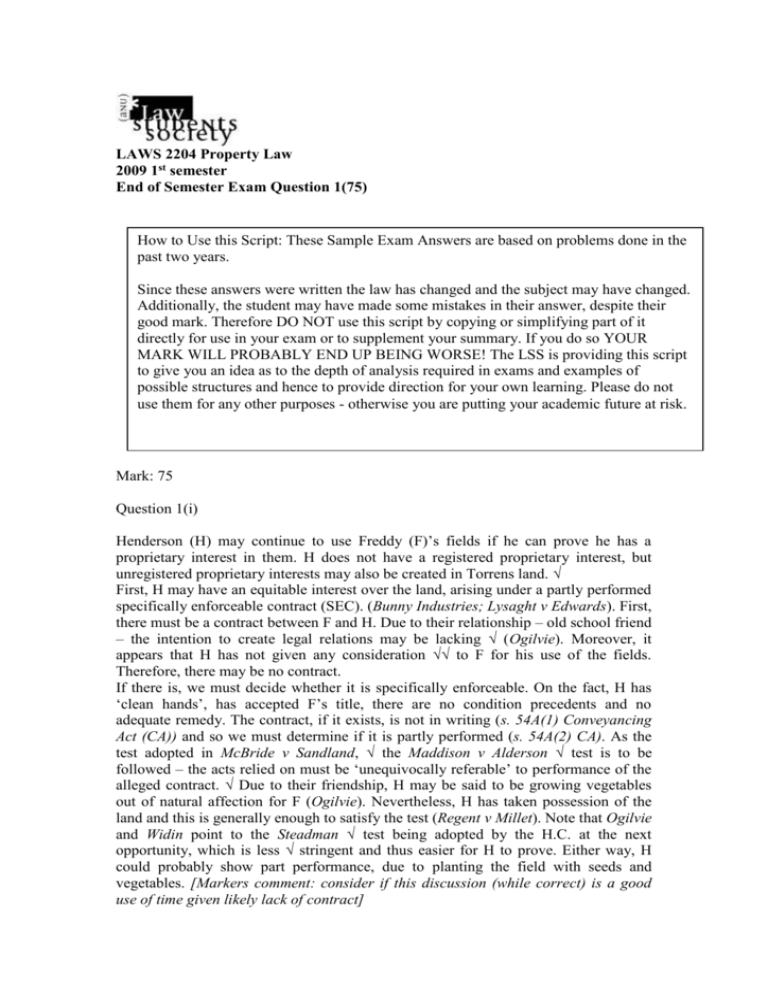

LAWS 2204 Property Law 2009 1st semester End of Semester Exam Question 1(75) How to Use this Script: These Sample Exam Answers are based on problems done in the past two years. Since these answers were written the law has changed and the subject may have changed. Additionally, the student may have made some mistakes in their answer, despite their good mark. Therefore DO NOT use this script by copying or simplifying part of it directly for use in your exam or to supplement your summary. If you do so YOUR MARK WILL PROBABLY END UP BEING WORSE! The LSS is providing this script to give you an idea as to the depth of analysis required in exams and examples of possible structures and hence to provide direction for your own learning. Please do not use them for any other purposes - otherwise you are putting your academic future at risk. Mark: 75 Question 1(i) Henderson (H) may continue to use Freddy (F)’s fields if he can prove he has a proprietary interest in them. H does not have a registered proprietary interest, but unregistered proprietary interests may also be created in Torrens land. √ First, H may have an equitable interest over the land, arising under a partly performed specifically enforceable contract (SEC). (Bunny Industries; Lysaght v Edwards). First, there must be a contract between F and H. Due to their relationship – old school friend – the intention to create legal relations may be lacking √ (Ogilvie). Moreover, it appears that H has not given any consideration √√ to F for his use of the fields. Therefore, there may be no contract. If there is, we must decide whether it is specifically enforceable. On the fact, H has ‘clean hands’, has accepted F’s title, there are no condition precedents and no adequate remedy. The contract, if it exists, is not in writing (s. 54A(1) Conveyancing Act (CA)) and so we must determine if it is partly performed (s. 54A(2) CA). As the test adopted in McBride v Sandland, √ the Maddison v Alderson √ test is to be followed – the acts relied on must be ‘unequivocally referable’ to performance of the alleged contract. √ Due to their friendship, H may be said to be growing vegetables out of natural affection for F (Ogilvie). Nevertheless, H has taken possession of the land and this is generally enough to satisfy the test (Regent v Millet). Note that Ogilvie and Widin point to the Steadman √ test being adopted by the H.C. at the next opportunity, which is less √ stringent and thus easier for H to prove. Either way, H could probably show part performance, due to planting the field with seeds and vegetables. [Markers comment: consider if this discussion (while correct) is a good use of time given likely lack of contract] If the apparent lack of a contract means that H cannot show he has a SEC with F, H may be able to prove he has an estoppel √√, created by F encouraging or generating an expectation of an interest in land in H, to H’s detriment (Inwards v Baker, modified by Crabbe). F’s statement: “H, we’re old friends, etc…” does create / encourage an expectation in H that he can plant on F’s land and this is to H’s detriment, due to the time and money H has spent showing and tending to the field. Therefore, H could probably argue he had an estoppel and as a remedy may well receive proprietary interest in the land. [Markers comment: consider if the detriment is enough, cf Crabbe and Inward facts] Question 1(ii) H would like to maintain his interest in the land, determined above. To do so, he must prove an exception to Maggie (M)’s indefeasible title. Under s. 42 of the RPA and following Frazer v Walker and Breskvar v Wall, the registered proprietor of land – M – has immediate title on registration √. H can only challenge this by proving a specified exception applies. H should be noted here that M is a volunteer. Does a volunteer take the same indefeasible title as a for-value purchaser? In NSW – where our problem takes place – volunteers do enjoy the same indefeasible title (Bogdanovic) √. In Victoria, the volunteer’s title is only as good as that which he inherited and therefore, M would be bound by all unregistered interests which affected F’s title (Rasmussen). Although the High Court has not decided this issue and could follow either decision. In Farah v Say-Dee, they indicated they would follow the NSW position. Therefore, I will continue as if M had indefeasible title. One exception open to M to defeat M’s title is fraud. Fraud is personal dishonesty or moral turpitude on the part of the RP (Butler v Fairclough) √ or collusion in personal dishonesty and moral turpitude with a third party (Efstratiou v Glantschnig). √ M being delighted at the thought of kicking H off the land and moreover, her deliberate misrepresentation to him that “everything will be OK” point to M being fraudulent (Loke Yew). Although mere notice √ is not fraud, (Wicks v Bennett) this case can be distinguished from Wicks since here M deliberately set out to cheat H out of his interest in the land [perhaps, can she argue otherwise at all?]. Therefore, H would most probably be able to prove M was fraudulent and her title would become defeasible, allowing H to continue farming the land, perhaps. [OK]. If not fraud, possibly an action in personam, arising out of a Bahr v Nicolay trust √. Potentially M saying she was sure everything would be OK is an acknowledgement of H’s interest such that M has undertaken to recognise H’s rights. However, M’s statement is very vague, “everything” does not relate specifically to M’s agreement with F √√ - unlike the specific reference in Bahr – and moreover, it is an oral representation, not written as in Bahr. Therefore, it is very unlikely to be a Bahr v Nicolay constructive trust. [Good]. Therefore, H could probably defeat M’s indefeasible title by proving she was fraudulent. In that case, H may be able to assert his equitable right or mere equity over the land over M. Question 1(iii) H here would like to continue leasing the land for the remainder of the 25 years and therefore must win a priority dispute with Gary (G). Both H and G have unregistered √ interests arising from a lack of registration. √ H – first in time – has an unregistered lease. Either the lease is an equitable lease √, arising out of part performance of a contract (Bunny Industries) or an implied legal lease. [Markers comment: but written document and no G suggests this is unnecessary]. To show his lease is a SEC, H must show there is a valid contract – appears OK – which is specifically enforceable. There is no adequate remedy at common law since damages are never adequate, we can assume H is √ ready, willing and able to perform his obligations – paying $25 a week – although we need more information, and H seems to have clean hands and to have accepted F’s title. The lease is in writing, so s. 54A(1) CA is met. Therefore, H probably has an equitable lease, arising out of a SEC. √ Otherwise, H may have an implied legal lease, if we assume he is in possession and paying rent, and F receiving it. In this case, however, F would merely need to give H 1 month’s notice before evicting him. [Yes]. The lease is longer than a year and so will be held to be an implied yearly lease (Moore v Dimond) √ and s. 127(1) CA states that 1 month’s notice need be given. √ Therefore, for H, it would be better √√ for him to show he has an equitable SEC, √ which equity would enforce in full. G has an unregistered (fee simple). To determine which interest takes priority, we must apply the first in time rule √ (Heid). However, if applicable s. 43A RPA may be able to protect G’s interest. s. 43A RPA is applicable because settlement occurred simultaneously [not necessarily] with H caveating. To gain the protection of s. 43A, G must meet three requirements. First, has there been a registrable dealing? Assuming √ the certificate of title is available to G and there are no errors in the registration documents, then yes √. Perhaps F is being difficult with the certificate of title, with G too, in which case, no registrable dealing. G is dealing with the RP √ - F. Finally, is there a legal estate, that is, was G a BFPVWN before settlement occurred (IAC Finance, Taylor J). G had no actual notice of H’s lease (s. 164(1)(a) CA), but may be fixed with constructive notice √ √ (s. 164(1)(a) CA) of H’s lease if G would have discovered the lease had he investigated the folio – no, not registered lease, so wouldn’t be on the folio – or if he had inspected the land. If G had inspected, he may well have noticed that H had planted things √, etc and if so, would have been required to inquire √ from H what his interest in the land was. [good!] Due to a lack of information, not sure if H has begun planting, so G may or may not be fixed with constructive notice. If so, he doesn’t get the protection of s. 43A RPA and we must go through the first in time rule to determine who has priority √ (Heid). The first in time will prevail, unless the equities are unequal. First, did G know of H’s interest? According to Moffet v Dillon, this knowledge definitely includes √ actual knowledge, but unclear if it also includes constructive. See above. Assuming no knowledge by G of H’s lease, is there a causal connection between H’s conduct and G getting his interest? H did not caveat his interest immediately on finding out about F’s delay (J&H Just and Butler v Fairclough). √ [Consider Person as well]. This may be postponing conduct if H was unable to protect himself in another way. As he did not have the C. o. T., this is not so and therefore H did cause G’s interest to be made, such that G’s interest should prevail. [Good discussion – maybe a little more analysis based on what misleading conduct and security of possession (if any).] There appear no mitigating circumstances in “justice and fairness” (Heid) and therefore G is probably either protected by s. 43A, unless he had constructive notice, or alternately, H’s interest will probably be delayed to G’s interest, due to his postponing conduct. √

![[Examiner comments] Property: LAWS2204 Semester 1 2003 Final](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/008580063_1-682c7ee710037d7b4e0580c389562e29-300x300.png)