Customer Value Measurement Methods: Measurement Model

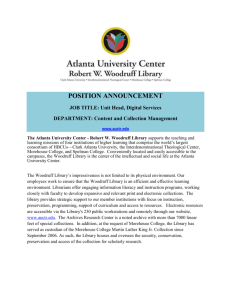

advertisement