chapter 15 summary

advertisement

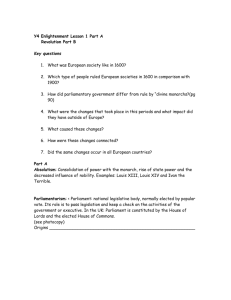

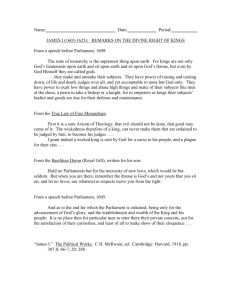

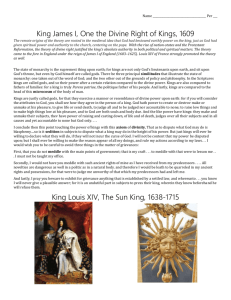

CHAPTER 15 SUMMARY The seventeenth century experienced economic recession and population decline as well as continued religious conflict between Catholics and Protestants. The breakdown of community and the growth of a more individualistic ethic resulted in a world of greater uncertainty. One reflection of anxieties was an epidemic of witchcraft accusations, usually against women. Protestant and Catholic animosities remained a prime cause for war, notably the Thirty Years War (1618-1648). There were also national and dynastic rivalries such as those between the Bourbon kings of France and the Habsburgs of Spain and the Holy Roman Empire. By the end, religious convictions had become secondary to secular political ambitions in public affairs. The Peace of Westphalia gave the German princes the right to determine the religion of their domains, France gained territory, Spanish power declined, and the Habsburg authority as German emperors was diminished. Conscript standing infantry armies became the norm. The century is known as the age of absolutism or the age of Louis XIV, although no seventeenth century ruler had the power of modern totalitarian dictators. Monarchs justified their absolutist claims by divine right–God had chosen kings to rule. Louis XIV (r.1643-1715), the Sun King, was the model for other rulers. His palace of Versailles symbolized his authority, where the aristocracy was entertained and controlled by ceremony and etiquette. Louis revoked his grandfather’s Edict of Nantes, and he fought four costly wars, mainly to acquire lands on France’s eastern borders. The Hohenzollern rulers of Brandenburg-Prussia became kings. Austrian power waned in the empire but it gained lands in the east and in Italy. Russia’s Peter the Great (r.1689-1725) attempted to westernize Russia, especially militarily, and built a new capital, St. Petersburg, to be his window on the west. The last major invasion by the Ottoman Empire into central of Europe resulted in its defeat in 1683. In Poland, the Sejm, or parliament, dominated by nobles and large landholders, controlled the state, but within the Sejm, a single negative vote vetoed the wishes of the majority, a prescription for continual chaos. Conversely, the oligarchic Dutch republic was a success. The States General was controlled by wealthy merchants, many from Amsterdam with its population of 200,000. During wars, the military leader, or stadholder, gained power. The Stuart kings of Scotland, advocates of divine right absolution, became the rulers of England in 1603. Religious disputes occurred within Protestantism, between the Church of England and Puritan reformers. Civil war between Charles I (r.1625-1649) and Parliament led to the creation of a republic, the Commonwealth. The monarchy was restored under Charles II (r.1660-1685). Parliament’s Test Act required worship in the Church of England to hold office. James II (r.1685-1688), a Catholic, suspended the law, and his Protestant daughter, Mary, and her husband, William of Orange, the Dutch stadholder, invaded. Before ascending the throne they accepted the Bill of Rights, limiting royal power. John Locke (d.1704) justified the Glorious Revolution, claiming that government is created by a social contract to protect the natural rights of life, liberty, and property, and if it fails to do so, there is a right of revolution. In art, Mannerism, with its emotional and religious content, was followed by the Baroque, which used dramatic effects to convey religious and royal power, which in turn gave way to French Classicism. Rembrandt (d.1669) made it the golden age of Dutch painting. It was also a golden age of theater with England’s Shakespeare (d.1616), Spain’s Lope de Vega (d.1635), and France’s Racine (d.1699) and Moliere (d.1673).