ABSTRACT

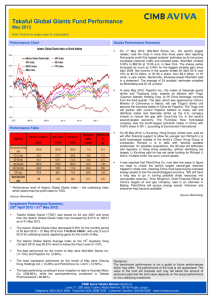

advertisement