Microsoft Word version

advertisement

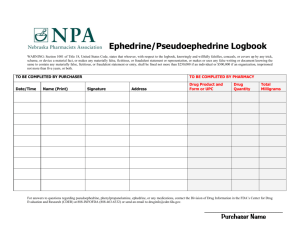

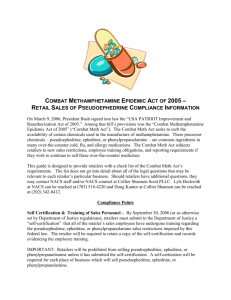

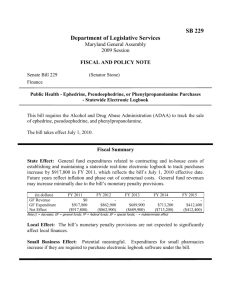

SENATE JUDICIARY COMMITTEE Senator Noreen Evans, Chair 2011-2012 Regular Session AB 1280 (Hill) As Amended May 26, 2011 Hearing Date: July 5, 2011 Fiscal: Yes Urgency: No BCP SUBJECT Ephedrine: Retail Sale DESCRIPTION This bill would require retailers to immediately transmit information regarding pseudoephedrine purchases to the National Precursor Log Exchange (NPLEx), a privately funded out-of-state database. That system would be required to provide retail distributors with an immediate real-time alert if a person attempts to purchase pseudoephedrine in violation of the sales limits. This bill would require the retail distributor to transmit information regarding the consumer to the database, including the consumer’s name, date of birth, and address and the product sold, the quantity of packages, and the total gram amount of pseudoephedrine involved in the sale. This bill would also repeal existing statutory provisions for over-the-counter sales of pseudoephedrine and related products and replace them with new sales limits consistent with federal law. This bill would impose additional restrictions on the sale of pseudoephedrine products in accordance with federal law, including that retail distributors must store those products in a locked cabinet or behind the counter. BACKGROUND Despite limits on purchases of pseudoephedrine, laboratory incidents in California rose in 2008 to 346. Many law enforcement agencies, including the Drug Enforcement Administration, have concluded that the rise in laboratories in 2008 resulted from an increase in “smurfing” of pseudoephedrine. Smurfing involves purchases of small amounts of pseudoephedrine from numerous drug stores. While smurfers may violate federal law in purchasing more than 9 grams in a month – although each purchase would not be over the 3.6 gram limit – the lack of adequate law enforcement personnel and resources to manually review purchase logs allows smurfing to continue. (more) AB 1280 (Hill) Page 2 of 16 In 2006, the federal Combat Methamphetamine Epidemic Act (CMEA) was enacted to restrict the retail sale of ephedrine, pseudoephedrine, norpseudoephedrine, or phenylpropanolamine. States have enacted limits on purchases of pseudoephedrine, imposed point-of-sale restrictions, or enacted pseudoephedrine tracking laws. Oregon has required a prescription for pseudoephedrine purchases since 2006. Mississippi has required a prescription since July 2010. Of the states that require electronic tracking (an arguable alternative to requiring a prescription), 14 out of the 16 use the National Precursor Log Exchange (NPLEx), funded by the manufacturers of pseudoephedrine products to track pseudoephedrine sales. Those purchase logs are then freely accessible by law enforcement with no requirement for a warrant. This bill would add California to that list of states by requiring retail distributors to send purchase information to NPLEx for purposes of determining whether a proposed sale would violate limit requirements. A substantially similar bill, AB 1455 (Hill, 2010) was held in this Committee last year due to privacy concerns. This bill was approved by the Senate Committee on Public Safety on June 21, 2011. CHANGES TO EXISTING LAW Existing law, the California Constitution, provides that all people have inalienable rights, including the right to pursue and obtain privacy. (Cal. Const. Art. I, Sec. 1.) Existing law, with specified and detailed exceptions, prohibits disclosure of medical information without the authorization of the patient. Medical information shall be disclosed pursuant to a court order or a warrant issued to a law enforcement agency. Other specific exceptions are enumerated. (Civ. Code Sec. 56.10.) Existing law provides that medical information can be disclosed “when otherwise specifically required by law.” (Civ. Code Sec. 56.10, subd. (b)(9).) Existing federal law includes the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) which, subject to specified exceptions and procedures, provides that medical information shall be confidential. (Pub. Law 104-191; 45 CFR 160, 164.) Existing law classifies controlled substances in five schedules according to their dangerousness and potential for abuse. (Health & Saf. Code Secs. 11054-11058.) Existing law includes the CURES (Controlled Substance Utilization Review and Evaluation System) system to provide for the electronic monitoring of the prescribing and dispensing of Schedule II, III and IV controlled substances. CURES provides for the electronic transmission of Schedule II, III and IV prescription data to the Department of Justice (DOJ) at the time prescriptions are dispensed. (Health & Saf. Code Sec. 11165.) AB 1280 (Hill) Page 3 of 16 Existing law provides that pharmacists, in filling a controlled substance prescription, shall provide to DOJ the patient’s name, date of birth, the name, form, strength, and quantity of the drug, and the pharmacy name, pharmacy number, and the prescribing physician information. (Health & Saf. Code Sec. 11165 (d).) Existing law provides that the DOJ may initiate the referral of the history of controlled substances dispensed to an individual, based on the CURES data, to licensed health care practitioners and pharmacists, as specified. (Health & Saf. Code Sec. 11165.1(b).) Existing law provides that the history of controlled substances dispensed to a patient based on CURES data that is received by a practitioner or pharmacist shall be considered medical information, as specified. (Health & Saf. Code Sec. 11165.1(c).) Existing law includes a detailed regulatory scheme for the production and distribution of specified chemicals that may be precursors to controlled substances, and provides that producers and users of precursor chemicals must obtain a permit from DOJ. Applications for permits must include documentation of legitimate uses for regulated chemicals. (Health & Saf. Code Sec. 11106.) Existing law requires any person or entity that sells, transfers, or otherwise furnishes a specified chemical precursor to another person or entity to submit a report to the DOJ, generally within 21 days, of each transaction. The report must include the identification information about the purchaser. (Health & Saf. Code Sec. 11100(d).) Existing law provides that it is unlawful for a retailer to sell in a single transaction more than three packages, or 9 grams, of a product that he or she knows to contain ephedrine, pseudoephedrine, norpseudoephedrine, or phenylpropanolamine. With specified exceptions, the three package-9 grams per transaction limitation applies to any product lawfully furnished over the counter without a prescription pursuant to applicable federal law. This offense is a misdemeanor, punishable by a county jail term of up to 6 months, a fine of up to $1,000, or both. (Health & Saf. Code Sec. 11100 (g)(3).) Existing federal law, the Combat Methamphetamine Epidemic Act (CMEA), includes detailed restrictions and requirements for the retail sale of ephedrine, pseudoephedrine, norpseudoephedrine, or phenylpropanolamine. These restrictions include, in part: no more than 3.6 grams may be sold in a single transaction; no more than 9 grams per customer may be sold in a one-month period; if the drug is obtained through postal or similar delivery, no more than 7.5 grams can be so obtained; the seller must maintain a written or electronic logbook of each sale, including the date of the transaction, the name and address of the purchaser, and the quantity sold; the purchaser must present valid identification, as specified, and the seller must verify the identification; the purchaser must sign a paper or electronic logbook, as specified; AB 1280 (Hill) Page 4 of 16 the seller must maintain these documents, as specified; and law enforcement shall have access to the information pursuant to regulations adopted by the DOJ. (21 U.S.C. Secs. 830(e), 844 (a).) Existing federal law includes an exception to the log book recording of transactions in the case of a transaction that involves a single package that contains not more than 60 milligrams of pseudoephedrine. (21 U.S.C. Sec. 841 (e)(1)(A)(iii).) Existing federal law requires retailers to retain purchase information for not less than two years. (21 U.S.C. Sec. 841(v)(6).) Existing federal regulations protect the privacy of individuals who purchase scheduled listed chemical products by restricting disclosure of information in logbooks as follows: the information shall be disclosed as appropriate to the Administration and to State and local law enforcement agencies; the logbook information shall not be accessed, used, or shared for any purpose other than compliance with CMEA or to facilitate a product recall; and a regulated seller who in good faith releases information in a logbook to Federal, State, or local law enforcement authorities is immune from civil liability for the release unless the release constitutes gross negligence or intentional, wanton, or willful misconduct. (21 C.F.R. Sec. 1314.45.) This bill would repeal existing statutory provisions for over-the-counter sales of pseudoephedrine and replace them with new purchase limits and electronic tracking of purchases. This bill would provide that a violation of either the sales limits or required procedures for a pseudoephedrine transaction is a misdemeanor, punishable on a first conviction by a fine of up to $1,000, a jail term of up to six months, or both. Upon a subsequent conviction, the maximum jail term is one year and the maximum fine is $10,000. This bill would include the following procedures and sales limits: a retailer must store pseudoephedrine products in a locked cabinet or behind the counter; a retailer may sell no more than 3.6 grams of pseudoephedrine within 24 hours and no more than 9 grams in a 30-day period; data recording shall not apply to sale of a single package containing no more than 60 milligrams of a product containing pseudoephedrine; the user must present valid photo identification; the retailer must record the following at the time of making a transaction: o the date of the transaction; o the type and number of the buyer’s identification, and the issuing agency; o the name, date of birth and address of the purchaser; o the name and quantity product sold, including gram weight; o the name or initials of the person making the sale; AB 1280 (Hill) Page 5 of 16 the retailer shall immediately transmit the information about the sale and the purchaser to the National Precursor Log Exchange (NPLEx) electronic monitoring system administered by the National Association of Drug Diversion Investigators (NADDI) for the purpose of determining whether or not the sale would exceed statutory limits; the retailer’s duty arises when the NPLEx system is available to retailers without cost; the purchaser must provide valid identification, as specified; and the purchaser must sign a written or electronic log. This bill would, provided that the DOJ executes a memorandum of understanding (MOU) governing access, require NADDI to forward California transaction records in NPLEx to the Department of Justice weekly and provide real-time access to NPLEx information to law enforcement in the state, as specified. This bill would additionally require the MOU to: state that no party to the MOU, nor any entity under contract to provide the electronic authorization and monitoring system, shall be authorized to use the information contained in the system or any purpose other than set forth in this bill, the federal Combat Methamphetamine Epidemic Act of 2005, or applicable regulation. The system operation would be authorized to analyze the information for the sole purpose of assessing and improving performance and efficacy of the system; and require that any retail distributor’s access to the database is limited solely to records of sales transactions made by that distributor, which shall be solely for the purposes of complying with federal law or this bill, or to respond to a duly authorized law enforcement request or court order. This bill would additionally: require the system to be capable of providing a retail distributor with an immediate real-time alert if a sale violates the legal limits; require the system’s security program to comply with security standards for the Criminal Justice Information System of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and may be audited once a year by the DOJ; provide that a retail distributor’s use of the system shall be subject to Section 56.101 of the Civil Code (imposes various requirements to preserve the confidentiality of the medical information); prohibit those distributors from maintaining any records collected under the system for longer than two years, or as otherwise required by federal law; require the system to record law enforcement access to the system by means of a unique access code for each individual accessing the system; each user’s history shall be maintained and maybe audited by the department; and allow the DOJ to submit recommendations to NADDI regarding system changes to assist in identifying false identification cards. AB 1280 (Hill) Page 6 of 16 This bill would require the State Board of Equalization to notify all retailers about the requirement to submit transactions to NPLEx no later than April 1, 2012. This bill would not apply to a health care practitioner with prescriptive authority who is currently licensed in the state. This bill would state the intent of the Legislature to preempt all local ordinances or regulations governing the sale by a retail distributor of over-the-counter products containing ephedrine, pseudoephedrine, norpseudoephedrine, or phenylpropanolamine. This bill would sunset on January 1, 2018. COMMENT 1. Stated need for the bill According to the author: AB 1280 provides teeth to existing federal law limiting the sales of pseudoephedrine (PSE) products. Federal law in place since 2006 has imposed both daily and monthly limits on quantities of products containing PSE that can be purchased. Consumers must specifically ask for the products (only available behind the counter), provide identification and sign a log book prior to completing a sale. Limits on PSE quantities were imposed as it is a primary ingredient in the manufacture of methamphetamine. However, the paper logs maintained by each store or pharmacy are independent. As such, there is no way for a retailer to know if an individual has already met or exceeded the federal limit. A criminal could easily go from one store to another and hence accumulate large quantities of PSE. AB 1280 requires California retailers selling PSE products over the counter to enter the purchase into an electronic log prior to completing the sale. The networked, unified, electronic log will immediately alert retailers if the consumer has exceeded the federal limits. If so, retailers would be required to stop the sale. The electronic log in AB 1280 will be both consumer and retailer friendly. The interaction for the consumer would be the same as under current law. The retailer would simply enter the information into an electronic log (i.e. a web based interface) as opposed to the existing paper log. Retailers will know in realtime whether or not the purchase will exceed the federal limits. The electronic log in AB 1280 would be both anti-criminal and pro-consumer. Criminals will have a much harder time violating federal law if each store he or AB 1280 (Hill) Page 7 of 16 she approaches knows immediately whether or not the purchase is legal. Simultaneously, AB 1280 will protect access to effective medication for the millions of California allergy sufferers. The Consumer Healthcare Products Association (CHPA), the trade association representing U.S. manufacturers of nonprescription medicines, further asserts: With NPLEx in place, retailers will obtain pre-approval from the system to make a sale, and over-limit sales are denied, stopping illegal sales before they happen. The sales data are maintained in a highly secure environment and, under federal law and the provisions of AB 1280, are legally available to law enforcement. Manufacturers fully fund NPLEx, so there is no charge to retailers, states, or law enforcement. In the states with the most critical meth lab problems, electronic tracking has been overwhelmingly the policy solution of choice for addressing the critical issue of PSE diversion. In addition, AB 1280 represents an alternative to proposals which would make these FDA approved products available only with a prescription. Such proposals are in extreme reaction and have serious negative health care access and fiscal impacts. As you know, over the counter medications are taxed at the point of sale while prescription medications are not. This measure, AB 1280, preserves the sales tax on these safe and effective products estimated at over $4M in 2010, while helping to safeguard the community from illicit meth production. 2. Background on the National Precursor Log Exchange (NPLEx) This bill seeks to require all retail distributors to use a database (NPLEx) that will store information regarding every person who purchases pseudoephedrine-based products within the state of California without a prescription – that tracking system would alert stores when a particular purchaser has exceeded the specified purchase limit. For background, the National Association of Drug Diversion Investigators (NADDI) 1 provides NPLEx at no cost to states. Funding for the NPLEx database comes from the manufacturers of pseudoephedrine products, and Appriss (a private company headquartered in Louisville, Kentucky) provides the software and houses the service in its data center. The bill would also allow the Department of Justice to execute a memorandum of understanding (MOU) with NADDI governing access to the database, which would also include language seeking to address the privacy of the information. NADDI (est. 1989) is a national non-profit organization that, according to its Web site, “facilitates cooperation between law enforcement, healthcare professionals, state regulatory agencies and pharmaceutical manufacturers in the investigation and prevention of prescription drug abuse and diversion. NADDI also sponsors and conducts specialized educational seminars and conferences.” NADDI is based in Maryland. The association has 21 state chapters, including California. 1 AB 1280 (Hill) Page 8 of 16 That unusual relationship between the State of California and NADDI raises not only questions about how California may enforce the provisions of a third party contract (NADDI with Appriss), but also the appropriateness of authorizing a database containing customers’ names, addresses, dates of birth, identification numbers, and names and quantities of pseudoephedrine to be maintained by that third-party outside of California. a. NADDI and Appriss The proposed requirement for retailers to submit transaction data to NPLEx appears to be consistent with a multi-state initiative by industry to implement an electronic tracking of over-the-counter sales of pseudoephedrine. That initiative is described as follows by the Consumer Healthcare Products Association (CHPA), a supporter, in their January 11, 2010 letter to the President of the Kansas Board of Pharmacy: On behalf of our member companies that make nonprescription PSE medicines, CHPA has offered to fully fund a PSE sales electronic tracking system in Kansas. CHPA’s proposal is the only one that meets the statutory funding requirement, allowing the Board of Pharmacy to meet its legislative directive. CHPA’s member companies have entered into exclusive contracts with the nation’s leading vendor of PSE e-tracking systems, and therefore are able only to provide funding for the system that has been offered to the Board. We are offering to provide this system, named the National Precursor Log Exchange (NPLEx), across multiple states as an integrated solution. . . . NADDI is a non-profit association that provides education and training for law enforcement agents on the diversion of pharmaceutical products. Its role in the NPLEx initiative is to enter into a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with the appropriate state agency, act as the administrator of NPLEx, and to liaise with law enforcement to ensure that NPLEx is understood and fully utilized. CHPA’s participating member companies are supporting NPLEx by paying a transactional fee based on sales of their PSE products. This funding stream fully supports NPLEx, meaning that the system can be deployed and maintained at no charge to retailers or to states. Access to NPLEx is available free of charge to any law enforcement agent who is properly authorized by the state. . . . Reflecting the priority that our member companies have put on delivering a single vendor platform for NPLEx, their contracts with Appriss and NADDI are exclusive, and therefore prohibit our companies from sponsoring systems operated by any other vendor. AB 1280 (Hill) Page 9 of 16 This bill represents the policy choice of joining other states in selecting a single outof-state private company to operate a database that would track purchases of pseudoephedrine products by requiring retailers to enter the purchaser’s personal information. That database, funded by the manufacturers of pseudoephedrine products, would log not only the individual’s personal information, but also the product they purchased. b. Lack of a direct contract with Appriss, a non-California company Although similar to the process in other states, this bill would take the unusual approach of requiring retailers to send sensitive information to NPLEx (an outof-state database run by a private company). This bill would allow the Department of Justice (DOJ) to enter into a Memorandum of Understanding with NADDI governing access, and require that MOU to state that no party to the MOU, nor any entity under contract to provide the database (Appriss), shall be authorized to use the information contained in the system for any purpose other than those set forth in the bill, federal law, or implementing regulations. The relationship between those parties raises legal issues of enforcement should Appriss use (or release) the information in NPLEx for unauthorized purposes. For example, if Appriss were to release information to manufacturers regarding customers who were purchasing pseudoephedrine based products, including name, address, type of product, and frequency of purchase, the question arises as to how that violation could be enforced. The action would arguably violate the intent of the MOU between the DOJ and NADDI, but Appriss is arguably not a party to that agreement. Additionally, since Appriss is located outside of California, some of California’s consumer protections may not apply to that release of information. As a result, while any MOU between the DOJ and NADDI would be required to include information restricting access to the database, it is unclear what legal restrictions (and California laws) would be enforceable on the actual vendor of the database who is arguably not a party to the agreement. DOES THIS BILL RAISE ENFORCEABILITY ISSUES? It is also unclear whether that Memorandum of Understanding would be a binding contract, or whether it would just represent a mutual agreement between parties (MOUs can be either, the key issue is whether the agreement itself meets the requirement of a contract, and in the absence of any funds changing hands (which would create the legal requirement of consideration) it is unclear whether the MOU would be a binding contract). Even if the MOU is a binding contract, the actual entity providing the service is another party, Appriss, who would not have a direct contractual relationship with DOJ. AB 1280 (Hill) Page 10 of 16 Given the contractual distance between the DOJ and Appriss, the Committee should consider whether the State of California has sufficient control and recourse to enforce the requirements imposed by this bill. DOES CALIFORNIA HAVE SUFFICENT CONTROL OVER APPRISS TO ADEQUATELY ENSURE THE PRIVACY OF CONSUMERS’ INFORMATION? c. Comparison to CURES Committee staff notes that there are alternatives to the proposed privately held, third-party database. Specifically, the CURES program provides for real-time electronic transmission of specified prescription data to DOJ. Under CURES, pharmacists, in filling a controlled substance prescription, must provide to DOJ the patient’s name, date of birth, the name, form, strength, and quantity of the drug, and the pharmacy name, pharmacy number, and the prescribing physician information. Essentially the data is analyzed for indications that controlled substances are being improperly prescribed, or that drug abusers are obtaining prescriptions for controlled substances from many different doctors (“doctor shopping”). Physicians and pharmacists, in addition to law enforcement, have access to CURES data through PAR – patient activity reports. Currently, a private contractor – Infinite Solutions Inc. (ISI) – collects CURES data for DOJ. Unlike the system proposed by this bill, that existing system serves as an example of the DOJ directly contracting with a third party for a similar system. That direct contracting allows DOJ to use a competitive bid process and select the company that is best suited for providing the service to the State of California – that process also provides DOJ with clear recourse should the system not meet the stated need or goals. SHOULD DOJ HAVE THE ABILITY TO CHOOSE THE VENDOR OF THE DATABASE? 3. Opposition’s concerns The opposition, consisting of consumer groups, narcotics officers, public defenders, and the California Attorney General’s Office raise numerous concerns about the mandated use of a privately run database. a. Database may not achieve stated goal of reducing methamphetamine labs Methamphetamine is a highly addictive, destructive drug that is unique in that it generally cannot be formulated without relying on a commercially produced compound (pseudoephedrine). To the extent that the distribution of pseudoephedrine to individuals who manufacture methamphetamine can be reduced, that reduction has a direct result in limiting the amount of produced AB 1280 (Hill) Page 11 of 16 product (although it can be argued that other meth producers out of the area may step in). Given the fundamental privacy issues that are raised by the requirement for retailers to submit customer information to an out-of-state privately run database, this bill raises a fundamental policy question about whether those privacy issues are outweighed by the benefits of the proposed system. Those potential benefits are difficult to quantify and must be examined in conjunction with a competing pending proposal to require prescriptions for pseudoephedrine products (which has not triggered privacy concerns). DO THE PRIVACY RISKS OUTWEIGH THE POTENTIAL BENEFITS? The California Attorney General’s Office, sponsor of pending prescription-only legislation, asserts that tracking systems in place in other states have failed to curtail the increase in methamphetamine labs and that implementation of the proposed tracking system would not address California’s methamphetamine problem, and, would simply act to delay implementation of a prescription only system. The Los Angeles County District Attorney’s Office contends that: . . . experience has shown this system is ineffective at keeping methamphetamine producers from obtaining the pseudoephedrine they need to cook meth. Our office notes, that the State of Kentucky is billed as the role model for the type of program that AB 1280 would establish. However the results of the electronic authorization and monitoring program in Kentucky have been disheartening at best and a complete failure at reducing the amount of methamphetamine labs at worst. Last year the State of Kentucky, utilizing it’s electronic authorization and monitoring law designed to keep pseudoephedrine out of the hands of methamphetamine producers, achieved the unsettling distinction of having more methamphetamine labs than at any other time in the state’s history. Alternatively, supporters point to the numerous sales that are blocked each month by retailers in participating states using the NPLEx database. It is unclear, however, whether the majority of those blocked sales are average individuals who are seeking allergy medicine who accidentally exceeded the legal limit, or, reflect a concerted effort by certain individuals to purchase those products for purposes of making methamphetamine. b. Law enforcement access This bill would allow law enforcement to access the information submitted by retailers, require that access to be recorded by means of a unique access code, and require each user’s history to be maintained and provide that the DOJ may audit that history. While the bill would allow DOJ to enter into an MOU with NADDI governing access, NADDI would be required to “provide real-time access to NPLEx information through the NPLEx online portal to law enforcement in the state as AB 1280 (Hill) Page 12 of 16 authorized by the department.” The ability to access that information would also apply to law enforcement in other states, thus, allowing a vast number of law enforcement to look through voluminous data regarding sales, and attempted sales, of pseudoephedrine. The Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) opposes the creation of a database of consumers “with easy access by law enforcement agencies without justification. Law enforcement access to prescription medication requires a search warrant under the California Confidentiality of Medical Information Act (CMIA). Furthermore, stores faced with law enforcement requests for information about people purchasing non-prescription medications require search warrants . . . AB 1280 treats ordinary Sudafed consumers as criminal suspects and raises serious concerns about consumer privacy and protections against unlawful search and seizure, as protected by the Fourth Amendment and our state constitution.” The American Civil Liberties Union, in an oppose unless amended position, further contends that: Law enforcement officials could follow up with individuals after their purchase of a packet of the common congestion remedy, “Sudafed,” and then grill them about why they purchased it, what their medical condition is, and other private information. These absurd results should be avoided.” Given the numerous stopped sales that arguably occur each day, it is unclear whether law enforcement (even if they were watching each transaction) would have the time or resources to investigate each stopped sale. Alternatively, given the voluminous data contained in the system, it is unclear how exactly law enforcement would identify a smurfer, as opposed to a mom that has kids with allergies who need more product than the law allows; additionally, it is unclear what steps smurfers are taking to circumvent the database in other states (such as fake IDs). Regarding single denials (which arguably are more likely to happen to an innocent person than an individual well acquainted with pseudoephedrine restrictions), the bill states that the “Legislature finds that it is necessary for probable cause to be demonstrated to trigger an investigation in connection with an individual whose requested purchase is denied by the system a single time.” That provision codifies an important point – just because an individual is denied a single purchase does not mean that the single denial, absent probable cause, should be sufficient to trigger an investigation. If that were the circumstance, many individuals who accidentally attempt to purchase an amount over the statutory limit could find themselves the subject of an investigation. Additionally, while law enforcement arguably has the authority under existing law to examine the paper log books of the individual stores, the act of placing that information in an electronic real-time easy to read format raises additional issues regarding privacy. The real-time data provides law enforcement (and the database provider) with detailed information about purchases of pseudoephedrine – the AB 1280 (Hill) Page 13 of 16 privacy implications of reviewing that information online are significantly greater than if law enforcement had to go to an individual store and examine the log book. Regarding that access, the California State Sheriffs’ Association (CSSA), in support, notes that the “electronic system contemplated allows law enforcement to monitor all sales in real-time and on a statewide basis which will greatly enhance suppression and investigative efforts.” In light of the above concerns, the Committee should consider whether, in fact, it is appropriate to require retailers to use a system to track purchases of pseudoephedrine products where law enforcement can monitor sales in real-time, without a warrant. SHOULD LAW ENFORCEMENT BE ABLE TO MONITOR SALES IN REAL-TIME WITHOUT A WARRANT? c. Limitations on retailers represent only half of the potential problem This bill would specifically provide that a retail distributor’s use of NPLEx shall be subject to Section 56.101 of the Civil Code. That Section, part of the Confidentiality of Medical Information Act (CMIA), generally requires health care providers that create, maintain, preserve, store, abandon, destroy, or dispose of medical records to do so in a manner that preserves the confidentiality of information; negligent actions are subject to specific remedies and penalties. This bill would also require the DOJ’s MOU to limit access by retailers to records of sales transactions made by that retailer, and provide that access is solely for purposes of complying with this bill, federal law, or to respond to law enforcement or court order. Retailers would also be prohibited from maintaining separate copies of transaction information, as specified. While those protections are appropriate for the individual stores that are accessing NPLEx and entering customer data, they would appear to cover only half of the transaction – namely, while the retailer is subject to various requirements, the provider of the database would not be subject to those same laws. For example, while this bill applies a provision of CMIA to a California retail store, it would not apply that same provision to Appriss (provider of the NPLEx database). By not applying that provision, or any other provisions of California law, it is unclear what control California actually could exert over NPLEx, the third-party out-of-state database run by Appriss. The Committee should consider whether the above fundamental privacy concerns, the lack of a direct contractual relationship between DOJ and Appriss, and the inability to apply California protections to NPLEx outweigh the arguable benefits of requiring this database. DO THE FUNDAMENTAL PRIVACY CONCERNS OUTWEIGH BENEFITS? It should be noted that Section 56.101 already applies to pharmacies and, as a result, the impact of this bill’s provision is to extend it to other “retail distributors” who are AB 1280 (Hill) Page 14 of 16 not already subject to its provisions. Yet, those additional entities are already required to safeguard their customers’ personal information under provisions of existing law that require businesses to protect customers’ personal information from unauthorized access, destruction, use, modification, or disclosure. d. Notification to consumers that their information will be entered into the database This bill would require the retail distributor to give notice to customers explaining that their identification and purchase data will be provided to law enforcement pursuant to this bill and federal law for purposes of determining the legality of a proposed sale. Notice may be given electronically, in writing, or through signs. This bill applies only to the sale of pseudoephedrine products for personal use to walk-in customers or in a face-to-face transaction. As a result, it is not clear how notice would be given electronically. For example, would notice on the retail distributor’s Web site meet this requirement? Or, would emailed notice suffice? In either case, the customer does not receive this important notification at the time of the transaction, which arguably lessens its impact. In fact, nothing in the bill requires that any of the notifications be provided at the time of the transaction. SHOULD NOTIFICATION BE GIVEN AT THE TIME OF THE TRANSACTION? Existing law currently exempts prescription sales of pseudoephedrine from overthe-counter sales limits. This bill would likewise exempt those sales from being included in the database. Because it could be argued that customers should know that they can purchase pseudoephedrine with a prescription and their personal information will not be included in the database, the Committee may wish to consider whether consumers should be notified of that fact. SHOULD CONSUMERS ALSO BE TOLD THAT THEY CAN AVOID THE COLLECTION OF THEIR INFORMATION IN A DATABASE BY OBTAINING A PRESCRIPTION FOR THEIR PSEUDOEPHEDRINE PURCHASE? 4. Other opposition concerns In addition to the above issues, the opposition asserts the following: Retailers should be prohibited from obtaining any information from the database other than a “stop sale” response; the database should be held by DOJ rather than a private company; security breach laws should apply (Civ. Code Sec. 1798.29); private right of action should be available if data is used, disclosed, or shared in violation of the law; an annual independent audit and public report of the use of the system by DOJ; an audit every three years of the effectiveness of the system; AB 1280 (Hill) Page 15 of 16 destruction of personal information at the time of expiration of the statute of limitations for prosecution of a purchaser; clear and conspicuous notice should be provided to each consumer before the individual purchases the ephedrine explaining that the information will be added to a database; and database must be encrypted and subject to stringent accessibility restrictions. 5. AB 1455 (Hill, 2010) and arguable privacy improvements As discussed above, this bill is similar to AB 1455 (Hill, 2010), which was held in this Committee. This committee’s analysis raised similar privacy issues as those raised above, and, additionally suggested that the bill should be amended to authorize DOJ to create and run the proposed database. Although the author elected not to accept that suggested amendment last year, a similar amendment would appear to address many of the concerns expressed above. Furthermore, in response to the privacy issues raised by this committee regarding AB 1455, supporters have provided committee staff with a list of specific privacy protections that are included in the bill. That list of “privacy protections” is as follows: prohibit retail distributors from using collected information for any purposes other than to comply with federal law; prohibit retail distributors from maintaining any separate copies of the transaction information except as may be required by federal law; require all retailers to provide a notice in writing or by signage that the information collected is pursuant to federal law; makes legislative finding that demonstration of probable cause is necessary for investigation of denial on a single occasion; should the DOJ sign the MOU with NADDI governing law enforcement access to NPLEx data, the MOU must provide that the information contained therein cannot be used for any purpose other than to enforce the federal law; the Confidentiality of Medical Information Act provisions and sanctions have been extended to the retailer’s use of the system. Despite those provisions, the Committee should consider whether the benefits of the bill, in its entirety, outweigh the fundamental privacy issues raised by mandating the use of a third-party out-of-state database funded by the manufacturers of pseudoephedrine based products. Support: Alameda County Sheriff’s Office; Alliance for Patient Access, California Chapter; Alameda Health Consortium; Bayer Health Care; BIOCOM; Calaveras County Sheriffs’ Department; California Alliance for Retired Americans; California Black Health Network; California Chamber of Commerce; California District Attorneys Association; California Healthcare Institute; California Hispanic Chamber of Commerce; California Manufacturers and Technology Association; California Medical Association; California AB 1280 (Hill) Page 16 of 16 Pharmacists Association; California Primary Care Association; California Retailers Association; California State Sheriffs’ Association; Community Clinic Association of LA County; Consumer Healthcare Products Association; Johnson and Johnson; Healthy African American Families II; Kern County Sheriff; Lassen County Sheriff’s Office; Los Angeles County Medical Association; Los Angeles Society of Allergy, Asthma & Clinical Immunology, Inc.; Marin Medical Society; Napa County Medical Society; National Association of Chain Drug Stores; National Federation of Independent Business; Orange County Business Council; Orange County Sheriff-Coroner Department; Peace Officers Research Association of California; Pfizer, Inc.; Reckitt Benckiser; Rite Aid; Sacramento County Sheriff's Department; San Francisco Chamber of Commerce; San Joaquin County Sheriff; Sanofi-Aventis; Santa Clara County Medical Association; Santa Cruz County Sheriff-Coroner; Shasta County Sheriff; Siskiyou County Sheriff’s Department; Solano County Medical Society; Sonoma County Medical Association; Valley Industry & Commerce Association (VICA); Walgreens; Yolo County Sheriff’s Department Opposition: American Civil Liberties Union; California Department of Justice; California Narcotics Officers’ Association; California Public Defenders Association; Electronic Frontier Foundation; Los Angeles County District Attorney; National Narcotics Officers Association Coalition; Privacy Rights Clearinghouse HISTORY Source: Author Related Pending Legislation: SB 315 (Wright), would require a prescription for pseudoephedrine products. This bill is in the Senate Health Committee. Prior Legislation: AB 1455 (Hill, 2010), would have enacted an electronic database substantially similar to that proposed by this bill. This bill was held in this Committee due to privacy concerns. SB 484 (Wright, 2009), would have required a prescription for pseudoephedrine products. This bill failed passage in the Assembly Public Safety Committee. Prior Vote: Senate Public Safety Committee (Ayes 6, Noes 0) Assembly Floor (Ayes 79, Noes 0) Assembly Appropriations Committee (Ayes 16, Noes 0) Assembly Public Safety Committee (Ayes 7, Noes 0) **************