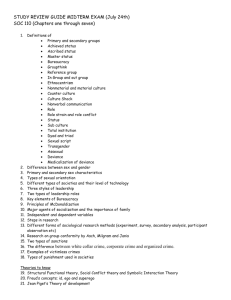

Key Elements of Problem Solving

advertisement