Aristotle's Persuasive Appeals

advertisement

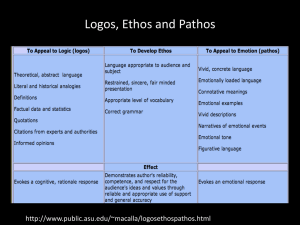

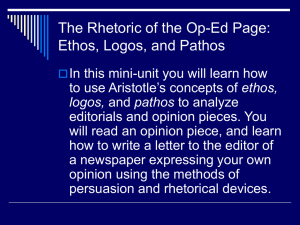

Aristotle’s Persuasive Appeals Over 2000 years ago, the Greek philosopher, Aristotle, student of Plato and teacher of Alexander the Great, identified four clusters of emotion and experience that “click” in the human brain to influence decisions—in other words, to persuade. Aristotle believed that good people needed to know these four appeals--not only because it was their ethical responsibility to persuade undecided people to The Good, but to defend themselves when these same appeals were wielded by unethical (i.e., bad) people. Ethos Ethos is appealing to the authority or credibility of the speaker or writer in order to persuade the listener. For example, Jack Nicholsen's character in “A Few Good Men,” has ethos to spare-medals, a reputation as a many-starred colonel, and the bearing to match. He describes himself as "an educated man," and he has many important connections that add to his credibility. Ethos is created through these 4 ways: 1. Known experience 2. Expertise 3. Credentials, certifications, professional standing 4. Polished presentation of the speaker's "self" or of the author's material (This is why teachers always tell you to spell check and proofread. How well you write is part of a first impression that builds or detracts from your ethos on paper.) Two examples of people using ethos: Pathos Pathos is using emotions--the full range of them--to persuade. When you see a commercial asking you to contribute money to starving children, that's pathos. Pathos persuades by inducing any of the following: 1. Guilt 2. Love 3. Security 4. Greed 5. Pity 6. Humor Two examples of people using pathos: Adapted from www.owatonna.k12.mn.us/classroom/ohs/language%20arts/eeitrheim/aristotle's%20persuasive% 20appeals.htm Nomos Best described as the use of shared cultural beliefs to persuade, nomos works like this: If I can find some common ground between us, I can use it to persuade you to do . . . whatever. Scholar and rhetorician Kenneth Burke calls this "identification" and says it was the most powerful persuasive tool at our disposal. (And my name-dropping there was a little ethos-building on my part.) Nomos, then, is invoked by looking for the following: 1. What do we have in common? 2. How can this be exploited or used to enlarge upon our similarities? 3. How can I use it to persuade you that, since I've come to this conclusion, so should you? Two examples of people using nomos: Logos For all of us critical thinkers, logos is the most essential part of the appeals team. While we need to be acutely aware of the emotional, social, and psychological forces at work, we need to be most attuned to logic, facts, evidence, or what most of us will agree is "real." For example, in courtroom scenes, evidence like sworn testimony, phone records, and legal documents make the logos pile bigger. Logos is invoked through the use of the following: 1. Details in writing (like photographs in evidence) 2. Statistics, if gathered with reliable methods 3. Expert testimony (and it's ethos that establishes the expert's expertise) 4. Facts (often subject to definition) 5. Definitions as used in the discipline being discussed 6. Witness statements under oath Two examples of people using logos: Adapted from www.owatonna.k12.mn.us/classroom/ohs/language%20arts/eeitrheim/aristotle's%20persuasive% 20appeals.htm