Reading Assignments

advertisement

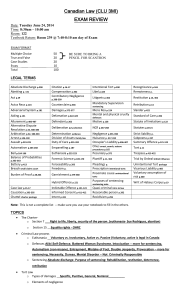

Torts II §132C Spring 2007 Susan Keller Reading Assignments The casebook for the course is Henderson, Pearson and Siliciano, The Torts Process (6th ed. 2003). All page references are to this text. Assignments labeled “handout” will be distributed ahead of time in class (handouts 1 and 2 are attached to this syllabus). Principle cases with starting page numbers in parentheses are noted for your reference. However, you should read all pages listed in the assignment. WEEK 1 (1/17) TOPICS ASSIGNMENT Review of Negligence Negligence Defenses: 353-364; Contributory Negligence 366-371 Assumption of Risk Comparative Negligence CASES See “First Assignment” sheet at WSU website Butterfield v. Forrester (353) Davies v. Mann (354) Meistrich v. Casino Arena (701) Knight v. Jewett (368) (1/24) Comparative Negligence and intentional torts; Trespass and Nuisance Handout 1; 379-386; Handout 2; 390-400 Merrill Crossings v. McDonald (handout 1) Ozaki v. Discovery Bay (handout 1) Friendship Farms v. Parson (handout 2) Adams v. Cleveland-Cliffs (390) Davis v. Georgia-Pacific (395) Waschak v. Moffat (397) 3 Trespass and Nuisance 403-412; Handout 3 Strict Liability 413-417 (top); 420-435 Boomer v. Atlantic Cement (403) Spur Industries v. Del E. Webb (408) Prah v. Maretti (handout 3) Turner v. Big Lake Oil Co. (420) Siegler v. Kuhlman (423) Foster v. Preston Mill Co. (431) Products Liability: Negligence theory Warranty theory 437-450; 2 (1/31) 4 (2/7) MacPherson v. Buick Motor Co. (439) Henningsen v. Bloomfield Motors (443) NO CLASS 2/14/06 5 (2/21) Products Liability: Strict Liability theory Warning defects 214-217; 451-468; 472; 481-500 (top) Escola v. Coca Cola (214) Vandermark v. Ford Motor Co. (451) Sheckells v. AGV Corp. (482) MacDonald v. Ortho Pharm. Corp. (489) Anderson v. Owens-Corning (495) WEEK 6 TOPICS ASSIGNMENT Products Liability: Design defects 500-502 (top) 508-534 Troja v. Black and Decker (508) Heaton v. Ford Motor Co. (516) Soule v. General Motors Corp. (520) Vautour v. Body Masters Sports (527) Products Liability: Comparative Negligence Practice Exams Midterm Review 473-500 Murray v. Fairbanks Morse (473) (2/28) 7/8 (3/6, 3/7) CASES SPRING BREAK 9 Midterm; Intro to Defamation 695-720 10 Defamation: First Amendment 720-732; Handout 4; 732-740 Gertz v. Robert Welch, Inc. (725) Dun & Bradstreet v.Greenmoss (handout) Wells v. Liddy (handout) Milkovich v. Lorain Journal Co. (732) 11 Invasion of Privacy: 1. Intrusion 741-754 Hamberger v. Eastman (744) Shulman v. Group W Productions (748) 12 Invasion of Privacy: 2. Public disclosure of private facts 754-773 Diaz v. Oakland Tribune (754) The Florida Star v. B.J.F. (764) 13 Invasion of Privacy: 3. False Light 4. Appropriation 773-784 Godbehere v. Phoenix Newspapers (773) Carson v. Here’s Johnny Portable Toilets (778) 14 Torts in Contract Settings 826-829; 833-839 (top) Wal-Mart v. Sturges (833) Review Exercises Handout #1 MERRILL CROSSINGS ASSOCIATES vs. LAWRENCE HOWARD MCDONALD SUPREME COURT OF FLORIDA 705 So. 2d 560; 1997 Fla. LEXIS 2033; 22 Fla. L. Weekly S 739 December 4, 1997, Decided OPINION: [*560] HARDING, J. McDonald was shot and injured by an unknown assailant on July 30, 1993, in the parking lot of a Jacksonville Wal-Mart store. He brought a personal injury suit against Wal-Mart and Merrill Crossings (the owner and developer of the shopping center) alleging failure to maintain reasonable security measures. The jury ruled in McDonald's favor, finding Wal-Mart seventy-five percent negligent and Merrill Crossings twenty-five percent negligent. Merrill Crossings recovered a judgment on its [**3] cross-claim for indemnity against WalMart plus attorney's fees and costs. Wal-Mart appealed. The First District Court of Appeal . . . ultimately concluded that excluding the assailant from the verdict form was not error. Section 768.81 codifies "Comparative Fault"; it provides in relevant part: *** (4) APPLICABILITY.-(a) This section applies to negligence cases. For purposes of this section, "negligence cases" includes, but is not limited to, civil actions for damages based upon theories of negligence, strict liability, products liability, professional malpractice whether couched in terms of contract or tort or breach of warranty and like theories. In determining whether a case falls within the term "negligence cases," the court shall look to the substance of the action and not the conclusory terms used by the parties. (b) This section does not apply . . . to any action based upon an intentional tort . . . . *** We . . . agree with the district court that the language excluding actions "based on an intentional tort" from the statute gives effect to a public policy that negligent tortfeasors such as in the instant [**8] case should not be permitted to reduce their liability by shifting it to another tortfeasor whose intentional criminal conduct was a foreseeable result of their negligence. See, e.g., Hall v. Billy Jack's, Inc, 458 So. 2d 760 (Fla. 1984) (lounge proprietor owes its patrons the duty to protect them from reasonably foreseeable harm); Holley v. Mt. Zion Terrace Apts., Inc., 382 So. 2d 98 (Fla. 3d DCA 1980) (the deliberate act of the rapist and murderer did not constitute an independent intervening cause which would insulate the landlord from liability for failing to provide reasonable security measures); see also Paterson v. Deeb, 472 So. 2d 1210 (Fla. 1st DCA 1985); Whelan v. Dacoma Enterprises, Inc., 394 So. 2d 506 (Fla. 5th DCA 1981); Rosier v. Gainsville Inns Associates, Ltd., 347 So. 2d 1100 (Fla. 1st DCA 1977) (a landlord's breach of an implied duty to provide locks and maintain common areas in safe condition may render landlord liable to the tenant for injuries resulting from unauthorized entry and criminal acts within the premises). The Restatement (Second) of Torts states, "If the likelihood that a third person may act in a particular manner is the [**9] hazard or one of the hazards which makes the actor negligent, such an act whether innocent, negligent, intentionally tortious, or criminal does not prevent the actor from being liable for harm caused thereby." Restatement (Second) of Torts, § 449 (1965). Thus, it would be irrational to allow a party who negligently fails to provide [*563] reasonable security measures to reduce its liability because there is an intervening intentional tort, where the intervening intentional tort is exactly what the security measures are supposed to protect against. Because we hold that section 768.81 is not applicable to the instant case, it was not error to exclude the intentional tortfeasor from the verdict form. BETTY J. OZAKI v. ASSOCIATION OF APARTMENT OWNERS OF DISCOVERY BAY; SUPREME COURT OF HAWAI'I 87 Haw. 265, 954 P.2d 644 April 14, 1998, Decided OPINION OF THE COURT BY LEVINSON, J. *** The issue presented is whether the intentional tort of a co-defendant deprives a defendant, against whom only negligence is alleged, of the protection of the modified comparative negligence rule set forth in Hawai'i Revised Statutes (HRS) § 663-31 (1993). *** I. BACKGROUND On July 4, 1990, Cynthia Dennis was murdered by Peter Sataraka, her estranged boyfriend, in her apartment in the Discovery Bay condominium complex (the condominium). On the night before the murder, Sataraka and Dennis had engaged in a confrontation at a nightclub. When Dennis left the nightclub without him, Sataraka proceeded to the condominium, where he and Dennis had lived together briefly prior to the incident. After Dennis failed to respond to Sataraka's attempt to contact her by "enterphone," Sataraka asked the security guard, Walker (who had frequently observed Sataraka entering the building with a key and/or in Dennis's company), to admit him into the building. After entering, Sataraka discovered that Dennis was not in her apartment; he therefore returned to the lobby and conversed with Walker. After Walker concluded his shift, Sataraka informed Walker's replacement that he was "waiting for his girlfriend." Dennis arrived home a short time later and encountered Sataraka, who followed her into her apartment. Dennis was found dead in her condominium the next day. Sataraka was thereafter tried and convicted of her second degree murder. Dennis's sister, Betty Ozaki, and mother, Teruko Dennis, (collectively, the plaintiffs) filed a complaint against Discovery Bay and Sataraka . . . . The complaint alleged that Discovery Bay had been negligent in providing security and that Walker had been negligent in "'allowing [Sataraka] through a security door and onto an elevator . . . which lead to [Dennis's] apartment.'" A jury found that the negligence of both Discovery Bay and Dennis had been causes of her death. In a special verdict, the jury apportioned ninety-two percent of the total fault to the intentional conduct of Sataraka, five percent to the negligent conduct of Dennis, and three percent to the negligent conduct of Discovery Bay. Discovery Bay moved for entry of final judgment in its favor pursuant to the special verdict, arguing that, because Dennis's negligence was greater than its own, recovery from Discovery Bay should be barred . . . . The plaintiffs countered that (1) because one of the tortfeasors had acted intentionally, Dennis's negligence could not be compared to the negligence of Discovery Bay pursuant to HRS § 663-31, (2) the jury should not have compared Dennis's negligence to Sataraka's intentional misconduct, and (3) notwithstanding the jury's determination of Dennis's greater negligence, Discovery Bay should be jointly and severally liable with Sataraka for all of Dennis's damages. Id. *** HRS § 663-31 provides in relevant part that "if the [proportion of negligence attributable to the person, for whose injury, damage, or death recovery is sought,] is greater than the negligence of the person or . . . the aggregate negligence of such persons against whom recovery is sought, the court will enter judgment for the defendant." Thus, by its plain language, the statute requires that judgment be entered in favor of Discovery Bay, inasmuch as the jury's special verdict apportioned greater fault to Dennis than to Discovery Bay. There is no discernible reason why Discovery Bay should lose the protection of HRS § 663-31 merely because its codefendant committed an intentional tort. The public policy underlying the decision to permit recovery in strict product liability actions subject only to reduction to the extent of the purely comparative degree of a plaintiff's contributory negligence--i.e., the "desire to create economic incentives for safer products," . . . simply has no bearing on the facts of this case. Thus, insofar as HRS § 663-31 governs the plaintiffs' negligence claim against Discovery Bay, the construct of pure comparative negligence is inapplicable thereto.