ath 255 - Miami University

advertisement

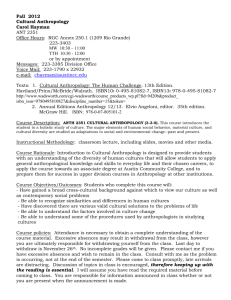

ATH 255 - FOUNDATIONS OF BIOLOGICAL ANTHROPOLOGY Course Syllabus Fall 2004 TR 2-3:15 p.m. 71 Upham 3 credit hours Office phone 9-1594 Dr. Linda F. Marchant Office 157 Upham Office hrs. T 9:30-11:30; TH 8-10 or by appointment Required Texts: Jurmain, R., Kilgore, L., Trevathan, W., Nelson, H. 2004. Essentials of Physical Anthropology, 5th ed. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Thomson Learning. Whitehead, P.F., Sacco, W.K., Hochgraf, S.B. 2005. A Photographic Atlas for Physical Anthropology, Brief Edition. Englewood, CO: Morton Publishing Company. A Reader, available at Oxford Copy Shop, 10 Poplar. [Your reader will be available after Aug. 30th at the latest] Course Description: [Please note - the prerequisite for this course is ATH 155] This course serves as an introduction to biological anthropology. We consider how an evolutionary perspective is essential to the life sciences. We review basic rules of inheritance, tackle the role of natural selection in the evolution of species, and address the relationship between populations and species. Our discussion of the palaeontological record begins with a review of vertebrate evolution. The focus then shifts to the order primates, including hominids. We examine the fossil record from the Paleocene through the Pleistocene, but link our examination to extant species’ morphology and behavior. In the last weeks of the course we return to the present and look at modern Homo sapiens sapiens as a biological organism. We consider issues like: population variation, population adaptation, and the human life course. Grading: Your grade is determined by: “Familiarization” Quiz 5% Exam 1 20% Exam 2 25% Final Exam 25% Book Review 20% Preparation & Participation 5% 100% Information about your Book Review is distributed on Aug. 24, 2004. Although Preparation & Participation (P&P) may look modest in that it accounts for 5% of your grade, it can make a difference, obviously. P&P will entail being called upon at random to respond to questions regarding the content of your textbook or other assigned readings. You may be asked to explain an evolutionary 1 mechanism, e.g. the role of mutation; clarify an issue in taxonomy, e.g., why is genus Pongo more distantly related to us than is genus Pan; and similar sorts of questions. The “Familiarization” Quiz is a chance for you to become familiar with how I structure objective questions on examinations. It too accounts for 5% of your grade; it will help you to prepare for the more extensive examinations. For the ”familiarization” quiz, you will have 25 minutes in which to complete 30 objective questions. Examinations are a combination of objective and written (short answer and short essay) sections. No make-up exams will be given, except by prior arrangement and documentation of serious illness or family death. Remember, please contact me either before the exam or on the day of the exam. Attendance policy: Attendance is taken every class meeting; if you have more than 5 un-excused absences during the semester, your final grade will be lowered one interval on the letter grade. For example, a B+ will be a B. COURSE OUTLINE WEEK OF: TOPIC TEXT -CHAPTER(S) Aug 24,26 The Evolutionary Perspective 1 Aug 31, Sept 2 History of Evolutionary Theory 2 Sept 7,9 Mon/Tues Switch, Mon classes meet Cell Biology 3 Sept 14,16 Cell Biology cont.; Heredity BOOK REVIEW SELECTION DUE, 9/14 “FAMILIARIZATION” QUIZ, 9/16 3,4 Sept 21,23 Heredity cont.; The Living Primates 4,5; W p.5-8 W p.10-12 Sept 28,30 The Living Primates cont. EXAMINATION 1 - SEPT. 30 5; W p.13-18 Oct 5,7 Primate Behavior 6 Oct 12,14 Macroevolution 7; W p.3132, p.43-53 2 Oct 19,21 Hominid Origins 8; W p.1922,29-30,5467 Oct 26,28 Homo erectus and contemporaries 9; W p. 6874 Nov 2,4 Guest Lecture: Dr. Clyde Snow, 11/2 Neandertals and other archaics Nov 9,11 Nov 16,18 EXAMINATION 2 – NOV. 9 Neandertals cont. Homo sapiens sapiens 10;W p.7889 10 11; W p.9095 Guest Lecture: Dr. William McGrew, 11/18 Nov 23 Human Variation BOOK REVIEW DUE IN CLASS 11/23 Thanksgiving Break 12 Nov 30, Dec 2 Human Variation cont. The Human Life Course 12,13 Dec 7,9 The Human Life Course cont. Prospects and Pitfalls 13,14 FINAL EXAMINATION - MONDAY, DEC. 13TH, 9:45 A.M. W indicates pages in Whitehead et al. See your Reader’s Table of Contents for related chapter material. 3 The Following Statement Appears in the Anthropology Majors Handbook Revised February 11, 2004 Academic Misconduct* The Department of Anthropology is committed to supporting the intellectual growth and academic potential of students through the development of new skills, the capacity for self-assessment, and advice from instructors. This learning process is undermined when students submit work that is not their own. Students who do so deny themselves the opportunity to practice skills essential to success at university and beyond. Students who engage in academic dishonesty cannot receive accurate assessments of their skills and they may also prevent other students from receiving accurate assessments of their knowledge or abilities. As a form of theft or deceit, such conduct is unethical and violates the relationships of trust and respect among students, their peers, and their instructor. Students who gain a grade dishonestly are only pretending to become educated, and defraud themselves and others (Whitley & Keith-Spiegel, 2002). Academic misconduct, as defined by the Miami University Student Handbook, covers a wide variety of activities, including copying or allowing others to copy one’s exams or assignments, turning in an assignment that the student has not written, and submitting the same material for more than one class. Instances of academic misconduct will be dealt with in accordance with the procedures outlined in the Student Handbook, which is available on-line at: http://www.miami.muohio.edu/documents_and_policies/handbook/ One form of academic dishonesty is plagiarism, which is presenting the work, words or ideas of another person as though they were one’s own, without giving the originator credit. For example, it is plagiarism to paraphrase material from another source without proper citation. Consider the following statement from Barbara Myerhoff’s 1980 ethnography Number Our Days: “Thus, in addition to being an intrinsic good, learning was a strategy for worldly gain.” It is plagiarism for the student to write the following in a paper: “Learning was not only inherently good, but a way to acquire worldly things.” Although a few words have been changed, the sentence is basically the same, and Myerhoff is not given credit. An acceptable sentence in a student paper would be, “Myerhoff (1980:92) notes that although learning was valued for its own sake, it was also “a strategy for worldly gain.” Here, Myerhoff is given credit for the idea, and her exact words are placed in quotation marks. The same rules apply to material from websites, and student work may be subject to online plagiarism searches. 4 Why do students cheat? Students sometimes cheat because they procrastinate on studying for a test or writing a paper. The Bernard B. Rinella, Jr. Learning Assistance Center in 23 CAB gives students help with time management and study skills. Students sometimes plagiarize because they are embarrassed to ask for help on writing assignments (Whitley, Jr. & Keith-Spiegel, 2002). The anthropology faculty encourage you to ask them for help, and the Center for Writing Excellence also provides a number of links on how to write a paper, including proper citation and how to avoid plagiarism: http://www.units.muohio.edu/cwe/Online_Resources.html. Students sometimes plagiarize because they believe instructors will think they are stupid or unoriginal if the paper is full of citations to other people’s work (Whitley, Jr. & Keith-Spiegel, 2002). This is a misconception: good scholarly work consists of organizing the ideas and evidence presented by other people as the foundation or support for argument. An extensive References Cited section is a strength in any paper. Students sometimes commit academic misconduct because they are unsure of the rules in a particular class, e.g., how much “working together” is acceptable. It is important to ASK your instructor for clarification of any questions you have about assignments. If you don’t ask, instructors will assume that your understanding of the assignment is the same as theirs. According to the Student Handbook, “Misunderstanding of the appropriate academic conduct will not be accepted as an excuse for academic misconduct.” Many students recognize that academic dishonesty hurts the student who does it. Students have noted the following: “You miss out on opportunities to master research and writing skills—two essential abilities in today’s marketplace” “You do not experience the gratification that comes from creating something that is distinctly your own,” and “If you commit plagiarism and it is discovered, your career is ruined before it starts” (Whitely, Jr. & Keith-Spiegel, 2002). Academic integrity is the foundation of self-respect and is the responsibility of every member of the Miami community. * This statement is copied, verbatim in some paragraphs, from Miami University’s Department of Psychology ad-hoc committee report on Academic Dishonesty, May 1, 2003. 5