Methodological Instructions to Practical Lesson

advertisement

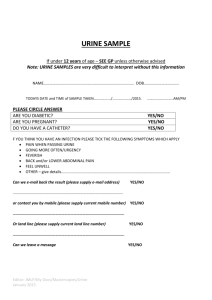

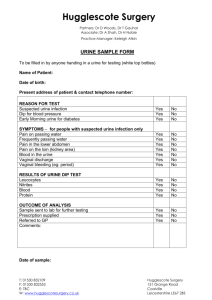

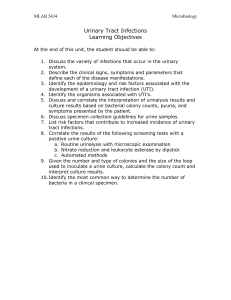

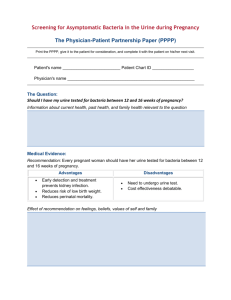

Methodological Instructions for Students Theme: Clinical and laboratory methods of Urological examination. Aim: To analyze the results of clinical and laboratory methods correctly. Professional Motivation: The urinalysis is a fundamental test that should be performed in all urologic patients. Although, in many instances, a simple dipstick urinalysis will provide the necessary information, a complete urinalysis includes both chemical and microscopic analyses. Basic Level: 1. You should know physical examination of the urine. 2. You should be able to determine pathology of urine sediment examination. 4. You should be able to make EPS and to know semen characteristics both in normal and pathology. Student's Independent Study Program I. Objectives for Students Independent Studies. You should prepare for the practical class using the existing textbooks and lectures. Special attention should be paid to the following: The physical examination of the urine includes an evaluation of color, turbidity, specific gravity and osmolality, and pH. The normal pale yellow color of urine is due to the presence of the pigment urochrome. Urine color varies most commonly because of concentration, but many foods, medications, metabolic products, and infection may produce abnormal urine color. This is important, because many patients will seek consultation primarily because of a change in their urine color. Thus, it is important for the urologist to be aware of the common causes of abnormal urine color. Freshly voided urine is clear. Cloudy urine is most commonly due to phosphaturia, a benign process in which excess phosphate crystals precipitate in an alkaline urine. Phosphaturia is intermittent and usually occurs after meals or ingestion of a large quantity of milk. Patients are otherwise asymptomatic. The diagnosis of phosphaturia can be accomplished either by acidifying the urine with acetic acid, which will result in immediate clearing, or by performing a microscopic analysis, which will reveal large amounts of amorphous phosphate crystals. Pyuria, usually associated with a UTI, is another common cause of cloudy urine. The large numbers of white blood cells cause the urine to become turbid. Pyuria is readily distinguished from phosphaturia either by smelling the urine (infected urine has a characteristic pungent odor) or by microscopic examination, which readily distinguishes amorphous phosphate crystals from leukocytes. Specific gravity of urine is easily determined from a urinary dipstick and usually varies from 1.001 to 1.035. Specific gravity usually reflects the patient's state of hydration, but may also be affected by abnormal renal function, the amount of material dissolved in the urine, and a variety of other causes mentioned later. A specific gravity less than 1.008 is regarded as dilute, and a specific gravity greater than 1.020 is considered concentrated. A fixed specific gravity of 1.010 is a sign of renal insufficiency, either acute or chronic. In general, specific gravity reflects the state of hydration, but also affords some idea of renal concentrating ability. Conditions that decrease specific gravity include (1) increased fluid intake, (2) diuretics, (3) decreased renal concentrating ability, and (4) diabetes insipidus. Conditions that increase specific gravity include (1) decreased fluid intake, (2) dehydration owing to fever, sweating, vomiting, and diarrhea, (3) diabetes mellitus (glucosuria), and (4) inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone. Specific gravity will also be increased above 1.035 after intravenous injection of iodinated contrast and in patients taking dextran. Urinary pH is measured with a dipstick test strip that incorporates two colorimetric indicators, methyl red and bromothymol blue, which yield clearly distinguishable colors over the pH range from 5 to 9. Urinary pH may vary from 4.5 to 8; the average pH varies between 5.5 and 6.5. A urinary pH between 4.5 and 5.5 is considered acidic, whereas a pH between 6.5 and 8 is considered alkaline. Chemical Examination of Urine Urine dipsticks provide a quick and inexpensive method for detecting abnormal substances within the urine. Dipsticks are short, plastic strips with small marker pads that are impregnated with different chemical reagents that react with abnormal substances in the urine to produce a colorimetric change. The abnormal substances commonly tested for with a dipstick include (1) blood, (2) protein, (3) glucose, (4) ketones, (5) urobilinogen and bilirubin, and (6) white blood cells. Normal urine should contain less than three red blood cells per HPF. A positive dipstick for blood in the urine indicates either hematuria, hemoglobinuria, or myoglobinuria. The chemical detection of blood in the urine is based on the peroxidase-like activity of hemoglobin. When in contact with an organic peroxidase substrate, hemoglobin catalyzes the reaction and causes subsequent oxidation of a chromogen indicator, which changes color according to the degree and amount of oxidation. Hematuria can be distinguished from hemoglobinuria and myoglobinuria by microscopic examination of the centrifuged urine; the presence of a large number of erythrocytes establishes the diagnosis of hematuria. If erythrocytes are absent, examination of the serum will distinguish hemoglobinuria and myoglobinuria. A sample of blood is obtained and centrifuged. In hemoglobinuria, the supernatant will be pink. This is because free hemoglobin in the serum binds to haptoglobin, which is water insoluble and has a high molecular weight. This complex remains in the serum, causing a pink color. Free hemoglobin will appear in the urine only when all of the haptoglobin-binding sites have been saturated. In myoglobinuria, the myoglobin released from muscle is of low molecular weight and water soluble. It does not bind to haptoglobin and is therefore excreted immediately into the urine. Therefore, in myoglobinuria the serum remains clear. Proteinuria Although healthy adults excrete 80 to 150 mg of protein in the urine daily, the qualitative detection of proteinuria in the urinalysis should raise the suspicion of underlying renal disease. Proteinuria may be the first indication of renovascular, glomerular, or tubulointerstitial renal disease, or it may represent the overflow of abnormal proteins into the urine in conditions such as multiple myeloma. Proteinuria also can occur secondary to nonrenal disorders and in response to various physiologic conditions such as strenuous exercise. The protein concentration in the urine obviously depends on the state of hydration, but it seldom exceeds 20 mg/dL. In patients with dilute urine, however, significant proteinuria may be present at concentrations less than 20 mg/dL. Normally, urine protein is about 30% albumin, 30% serum globulins, and 40% tissue proteins, of which the major component is Tamm-Horsfall protein. This profile may be altered by conditions that affect glomerular filtration, tubular reabsorption, or excretion of urine protein, and determination of the urine protein profile by such techniques as protein electrophoresis may help determine the etiology of proteinuria. Most causes of proteinuria can be categorized into one of three categories: glomerular, tubular, or overflow. Glomerular proteinuria is the most common type of proteinuria and results from increased glomerular capillary permeability to protein, especially albumin. Glomerular proteinuria occurs in any of the primary glomerular diseases such as IgA nephropathy or in glomerulopathy associated with systemic illness such as diabetes mellitus. Glomerular disease should be suspected when the 24-hour urine protein excretion exceeds 1 g and is almost certain to exist when the total protein excretion exceeds 3 g. Tubular proteinuria results from failure to reabsorb normally filtered proteins of low molecular weight such as immunoglobulins. In tubular proteinuria, the 24-hour urine protein loss seldom exceeds 2 to 3 g, and the excreted proteins are of low molecular weight rather than albumin. Disorders that lead to tubular proteinuria are commonly associated with other defects of proximal tubular function, such as glucosuria, aminoaciduria, phosphaturia, and uricosuria (Fanconi's syndrome). Overflow proteinuria occurs in the absence of any underlying renal disease and is due to an increased plasma concentration of abnormal immunoglobulins and other low-molecular-weight proteins. The increased serum levels of abnormal proteins result in excess glomerular filtration that exceeds tubular reabsorptive capacity. The most common cause of overflow proteinuria is multiple myeloma, in which large amounts of immunoglobulin light chains are produced and appear in the urine (Bence Jones protein). Leukocyte Esterase and Nitrite Tests Leukocyte esterase activity indicates the presence of white blood cells in the urine. The presence of nitrites in the urine is strongly suggestive of bacteriuria. Thus, both of these tests have been used to screen patients for UTIs. Although these tests may have application in nonurologic medical practice, the most accurate method to diagnose infection is by microscopic examination of the urinary sediment to identify pyuria and subsequent urine culture. All urologists should be capable of performing and interpreting the microscopic examination of the urinary sediment. Therefore, leukocyte esterase and nitrite testing are less important in a urologic practice. For purposes of completion, however, both techniques are described briefly herein. Urinary Sediment If possible, the first morning urine specimen is the specimen of choice and should be examined within 1 hour. A standard procedure for preparation of the urine for microscopic examination has been described (Cushner and Copley, 1989). About 10 to 15 mL of urine should be centrifuged for 5 minutes at 3000 rpm. The supernatant is then poured off, and the sediment resuspended in the centrifuge tube by gently tapping the bottom of the tube. Although the remaining small amount of fluid can be poured onto a microscope slide, this usually results in excess fluid on the slide. It is better to use a small pipette to withdraw the residual fluid from the centrifuge tube and to place it directly on the microscope slide. This usually results in an ideal volume of between 0.01 and 0.02 mL of fluid deposited on the slide. The slide is then covered with a cover slip. The edge of the cover slip should be placed on the slide first to allow the drop of fluid to ascend onto the cover slip by capillary action. The cover slip is then gently placed over the drop of fluid, and this technique allows for most of the air between the drop of fluid and the cover slip to be expelled. If one simply drops the cover slip over the urine, the urine will disperse over the slide, and there will be a considerable number of air bubbles that may distort the subsequent microscopic examination. Microscopic analysis of the urinary sediment should be performed with both low-power (×100 magnification) and high-power (×400 magnification) lenses. The use of an oil immersion lens for higher magnification is seldom, if ever, necessary. Under low power, the entire area under the cover slip should be scanned. Particular attention should be given to the edges of the cover slip, where casts and other elements tend to be concentrated. Low-power magnification is sufficient to identify erythrocytes, leukocytes, casts, cystine crystals, oval fat macrophages, and parasites such as Trichomonas vaginalis and Schistosoma hematobium. Erythrocyte morphology may be determined under high-power magnification. Although phase contrast microscopy has been used for this purpose, circular (nonglomerular) erythrocytes can generally be distinguished from dysmorphic (glomerular) erythrocytes under routine bright-field high-power magnification (Color Plates I–1 to I–5). This is facilitated by adjusting the microscope condenser to its lowest aperture, thus reducing the intensity of background light. This allows one to see fine detail not evident otherwise and also creates the effect of phase microscopy because cell membranes and other sedimentary components stand out against the darkened background. Normal urine should not contain bacteria, and, in a fresh uncontaminated specimen, the finding of bacteria is indicative of a UTI. Since each HPF views between 1/20,000 and 1/50,000 mL, each bacterium seen per HPF signifies a bacterial count of more than 20,000/mL. Therefore, 5 bacteria/HPF reflects colony counts of about 100,000/mL. This is the standard concentration used to establish the diagnosis of a UTI in a clean-catch specimen. This level should apply only to women, however, in whom a clean-catch specimen is frequently contaminated. The finding of any bacteria in a properly collected midstream specimen from a male should be further evaluated with a urine culture. Expressed Prostatic Secretions Although not strictly a component of the urinary sediment, the expressed prostatic secretions should be examined in any man suspected of having prostatitis. Normal prostatic fluid should contain few, if any, leukocytes, and the presence of a larger number or clumps of leukocytes is indicative of prostatitis. Oval fat macrophages are found in postinfection prostatic fluid (Color Plates I–18 and I–19). Normal prostatic fluid contains numerous secretory granules that resemble but can be distinguished from leukocytes under high power because they do not have nuclei. Key words and phrases: Color, turbidity, specific gravity and osmolality, pH, hematuria, proteinuria. II. Tests and Assignments for Self-assessment 1. Causes of renal anuria are: A. Incompatible blood transfusion. B. Shock, collapse. C. Gall-stones in ureters. D. Ureters'bandaging during gynaecologic operations. E. Nephrectomy of solitary kidney. 2. A frequent urination with normal diuresis is: A. Polyuria. B. Polydipsia. C. Pollakuria. D. Policetemia. E. Dysuria. 3. Which diurnal diuresis could be related to oliguria? A. from 250 to 500 ml. B. from 150 to 700ml. C. from 0 to 50 ml. D. from 100 to 500 ml. E. from 50 to 200 ml. 4. Which diurnal diuresis could be related to polyuria? A. over 2000 ml. B. over 3500 ml. C. 1500-2000 ml. D. 1000-1500 ml. E. over 1000ml. Multiple choice. Choose the correct answer/statement: Real life situations to be solved: 1. Patient S., at the age of 69; was admitted to the urology department, his complaints are urinary difficulty, increased urinary frequency, bloody urine. Examination: dullness of the percussion sound above the symphisis after urination. Pastematzkiy's symptom is negative. The urination is 4 times during the night. How the urinary difficulty and the urinary frequency called? How the bloody urine is called? Diseases that these symptoms are typical for. What does the dullness of the percussion sound mean? 2. Patient C., at the age of 52, was admitted at the urology department; his complained of left low back pains, absence of urine for 2 days. There is one fact from his case history: patient suffers from urolithiasis for 12 years. The operation of right side nephrectonomy 3 years ago. What is a preliminary diagnosis? How is it possible to differentiate acute urinary retention from anuria? III. Answers to the Self-assessment. The correct answers to the tests: 1. A. 2. C. 3. D. 4. A. The correct answers to the real life situations: 1. Stranguria. Hematuria. These symptoms are typical for nonmalignant hyperplasia of prostate. Chronic urinary retention. 2. Left side renal colic. Postrenal anuria. To provide catheterization of urinary bladder. Visual Aids and Material Tools: 1. Slides. 2. Results of analisis. 3. Tables. Students Practical Activities: Students must know: 1. Anatomy and physiology of ureters, kidneys, urinary bladder, urethra. 2. Aetiology of renal colic. 3. Main symptoms of urologic diseases. 4. Altered urination. 5. Abnormal urine specimen. 6. The constants of general urine specimen examination test of Zemnitski, biochemical indicators of blood. Students should be able to: 1. Provide catheterisation of urinary bladder with rubber catheter. 2. Measure residual urine volume. 3. Determine main symptoms of urologic diseases. 4. Analyze datas from the antecedent history that could be related to altered urination. 5. Analyze datas of diagnostic tests (general urine specimen examination, urine examination by Netchyporenko, Amburge, test of Zemnitski). 6. Provide palpation and percussion of the kidneys and urinary bladder. 7. Analyze semen test in urologic pathology.