The Original Affluent Society

advertisement

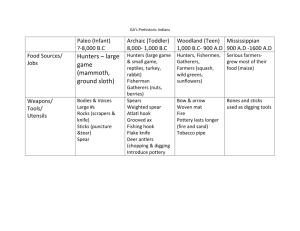

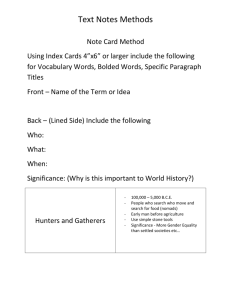

The Original Affluent Society -by Marshall Sahlins Hunter-gatherers Hunter-gatherers consume less energy per capita per year than any other group of human beings. Yet when you come to examine it the original affluent society was none other than the hunter's - in which all the people's material wants were easily satisfied. To accept that hunters are affluent is therefore to recognise that the present human condition of man slaving to bridge the gap between his unlimited wants and his insufficient means is a tragedy of modern times. There are two possible courses to affluence. Wants may be "easily satisfied" either by producing much or desiring little The familiar conception, the Galbraithean waybased on the concept of market economies- states that man's wants are great, not to say infinite, whereas his means are limited, although they can be improved. Thus, the gap between means and ends can be narrowed by industrial productivity, at least to the point that "urgent goods" become plentiful. But there is also a Zen road to affluence, which states that human material wants are finite and few, and technical means unchanging but on the whole adequate. Adopting the Zen strategy, a people can enjoy an unparalleled material plenty - with a low standard of living. That, I think, describes the hunters. And it helps explain some of their more curious economic behaviour: their "prodigality" for example- the inclination to consume at once all stocks on hand, as if they had it made. Free from market obsessions of scarcity, hunters' economic propensities may be more consistently predicated on abundance than our own. Destutt de Tracy, "fish-blooded bourgeois doctrinaire" though he might have been, at least forced Marx to agree that "in poor nations the people are comfortable", whereas in rich nations, "they are generally poor". Sources of the Misconception "Mere subsistence economy", "limited leisure save in exceptional circumstances", incessant quest for food", "meagre and relatively unreliable" natural resources, "absence of an economic surplus", "maximum energy from a maximum number of people" so runs the fair average anthropological opinion of hunting and gathering The traditional dismal view of the hunters' fix goes back to the time Adam Smith was writing, and probably to a time before anyone was writing. Probably it was one of the first distinctly neolithic prejudices, an ideological appreciation of the hunter's capacity to exploit the earth's resources most congenial to the historic task of depriving him of the same. We must have inherited it with the seed of Jacob, which "spread abroad to the west, and to the east, and to the north", to the disadvantage of Esau who was the elder son and cunning hunter, but in a famous scene deprived of his birthright. Current low opinions of the hunting-gathering economy need not be laid to neolithic ethnocentrism. Bourgeois ethnocentrism will do as well. The existing business economy Will promote the same dim conclusions about the hunting life. Is it so paradoxical to contend that hunters have affluent economies, their absolute poverty notwithstanding? Modern capitalist societies, however richly endowed, dedicate themselves to the proposition of scarcity. Inadequacy of economic means is the first principle of the world's wealthiest peoples. The market-industrial system institutes scarcity, in a manner completely without parallel. Where production and distribution are arranged through the behaviour of prices, and all livelihoods depend on getting and spending, insufficiency of material means becomes the explicit, calculable starting point of all economic activity. The entrepreneur is confronted with alternative investments of a finite capital, the worker (hopefully) with alternative choices of remunerative employ, and the consumer... Consumption is a double tragedy: what begins in inadequacy will end in deprivation. Bringing together an international division of labour, the market makes available a dazzling array of products: all these Good Things within a man's reach- but never all within his grasp. Worse, in this game of consumer free choice, every acquisition is simultaneously a deprivation for every purchase of something is a foregoing of something else, in general only marginally less desirable, and in some particulars more desirable, that could have been had instead. That sentence of "life at hard labour" was passed uniquely upon us. Scarcity is the judgment decreed by our economy. And it is precisely from this anxious vantage that we look back upon hunters. But if modern man, with all his technological advantages, still lacks the wherewithal, what chance has the naked savage with his puny bow and arrow? Having equipped the hunter with bourgeois impulses and palaeolithic tools, we judge his situation hopeless in advance. Yet scarcity is not an intrinsic property of technical means. It is a relation between means and ends. We should entertain the empirical possibility that hunters are in business for their health, a finite objective, and that bow and arrow are adequate to that end. The anthropological disposition to exaggerate the economic inefficiency of hunters appears notably by way of invidious comparison with neolithic economies. Hunters, as Lowie (1) put it blankly, "must work much harder in order to live than tillers and breeders" (p. 13). On this point evolutionary anthropology in particular found it congenial, even necessary theoretically, to adopt the usual tone of reproach. Ethnologists and archaeologists had become neolithic revolutionaries, and in their enthusiasm for the Revolution spared nothing in denouncing the Old (Stone Age) Regime. It was not the first time philosophers would relegate the earliest stage of humanity rather to nature than to culture. ("A man who spends his whole life following animals just to kill them to eat, or moving from one berry patch to another, is really living just like an animal himself"(2) (p.122). The hunters thus downgraded, anthropology was freer to extol the Neolithic Great Leap Forward: a main technological advance that brought about a "general availability of leisure through release from purely food-getting pursuits".(3) In an influential essay on "Energy and the Evolution of Culture", Leslie White (5, 6) explained that the neolithic generated a "great advance in cultural development... as a consequence of the great increase in the amount of energy harnessed and controlled per capita per year by means of the agricultural and pastoral arts". White further heightened the evolutionary contrast by specifying human effort as the principal energy source of palaeolithic culture, as opposed to the domesticated plant and animal resources of neolithic culture. This determination of the energy sources at once permitted a precise low estimate of hunters' thermodynamic potential- that developed by the human body: "average power resources" of one twentieth horse power per capita -even as, by eliminating human effort from the cultural enterprise of the neolithic, it appeared that people had been liberated by some labour-saving device (domesticated plants and animals). But White's problematic is obviously misconceived. The principal mechanical energy available to both palaeolithic and neolithic culture is that supplied by human beings, as transformed in both cases from plant and animal source, so that, with negligible exceptions (the occasional direct use of non-human power), the amount of energy harnessed per capita per year is the same in palaeolithic and neolithic economies- and fairly constant in human history until the advent of the industrial revolution.(5) Marvelously varied diet Marginal as the Australian or Kalahari desert is to agriculture, or to everyday European experience, it is a source of wonder to the untutored observer "how anybody could live in a place like this". The inference that the natives manage only to eke out a bare existence is apt to be reinforced by their marvelously varied diets. Ordinarily including objects deemed repulsive and inedible by Europeans, the local cuisine lends itself to the supposition that the people are starving to death. It is a mistake, Sir George Grey (7) wrote, to suppose that the native Australians "have small means of subsistence, or are at times greatly pressed for want of food". Many and "almost ludicrous" are the errors travellers have fallen into in this regard: "They lament in their journals that the unfortunate Aborigines should be reduced by famine to the miserable necessity of subsisting on certain sorts of food, which they have found near their huts; whereas, in many instances, the articles thus quoted by them are those which the natives most prize, and are really neither deficient in flavour nor nutritious qualities". To render palpable "the ignorance that has prevailed with regard to the habits and customs of this people when in their wild state", Grey provides one remarkable example, a citation from his fellow explorer, Captain Stuart, who, upon encountering a group of Aboriginals engaged in gathering large quantities of mimosa gum, deduced that the "unfortunate creatures were reduced to the last extremity, and, being unable to procure any other nourishment, had been obliged to collect this mucilaginous". But, Sir George observes, the gum in question is a favourite article of food in the area, and when in season it affords the opportunity for large numbers of people to assemble and camp together, which otherwise they are unable to do. He concludes: "Generally speaking, the natives live well; in some districts there may be at particular seasons of the year a deficiency of food, but if such is the case, these tracts are, at those times, deserted. It is, however, utterly impossible for a traveller or even for a strange native to judge. whether a district affords an abundance Of food, or the contrary... But in his own district a native is very differently situated; he knows exactly what it produces, the proper time at which the several articles are in season, and the readiest means of procuring them. According to these circumstances he regulates his visits to different portions of his hunting ground; and I can only say that l have always found the greatest abundance in their huts."(8) In making this happy assessment, Sir George took special care to exclude the lumpenproletariat aboriginals living in and about European towns -The exception instructive. It evokes a second source of ethnographic misconceptions: the anthropology of hunters is largely an anachronistic study of ex-savages an inquest into the corpse of one society, Grey once said, presided over by members of another. "A Kind of Material Plenty" Considering the poverty in which hunters and gatherers live in theory, it comes as a surprise that Bushmen who live in the Kalahari enjoy "a kind of material plenty", at least in the realm of everyday useful things, apart from food and water: "As the !Kung come into more contact with Europeans and this is already happening they will feel sharply the lack of our things and will need and want more. It makes them feel inferior to be without clothes when they stand among strangers who are clothed. But in their own life and with their own artifacts they were comparatively free from material pressures. Except for food and water (important exceptions!) of which the Nyae Nyae Kung have a sufficiency - but barely so, judging from the fact that all are thin though not emaciated - they all had what they needed or could make what they needed, for every man can and does make the things that men make and every woman the things that women make... They lived in a kind of material plenty because they adapted the tools of their living to materials which lay in abundance around them and which were free for anyone to take (wood, reeds, bone for weapons and implements, fibres for cordage, grass for shelters). or to materials which were at least sufficient for the needs of the population.... The !Kung could always use more ostrich egg shells for beads to wear or trade with, but, as it is, enough are found for every woman to have a dozen or more shells for water containers all she can carry and a goodly number of bead ornaments. In their nomadic hunting-gathering life, travelling from one source Of food to another through the seasons, always going back and forth between food and water, they carry their young children and their belongings. With plenty of most materials at hand to replace artifacts as required, the !Kung have not developed means of permanent storage and have not needed or wanted to encumber. themselves with surpluses or duplicates. They do not even want to carry one of everything. They borrow what they do not own. With this ease, they have not hoarded, and the accumulation of objects has not become associated with status.."(9) In the non subsistence sphere, the people's wants are generally easily satisfied. Such "material plenty" depends partly upon the simplicity of technology and democracy of pro perty. Products are homespun: of stone, bone, wood, skin-materials such as "lay in abundance around them". As a rule, neither extraction of the raw material nor its working up take strenuous effort. Access to natural resources is typically direct- "free for anyone to take"- even as possession of the necessary tools is general and knowledge of the required skills common. The division of labour is likewise simple, predominantly a division of labour by sex. Add in the liberal customs of sharing, for which hunters are properly famous, and all the people can usually participate in the going prosperity, such as it is. For most hunters, such affluence without abundance in the non-subsistence sphere need not be long debated. A more interesting question is why they are content with so few possessions for it is with them a policy, a "matter of principle" as Gusinde 10 says, and not a misfortune. But are hunters so undemanding of material goods because they are themselves enslaved by a food quest "demanding maximum energy from a maximum number of people", so that no time or effort remains for the provision of other comforts? Some ethnographers testify to the contrary that the food quest is so successful that half the time the people seem not to know what to do with themselves. On the other hand, movement is a condition of this success, more movement in some cases than others, but always enough to rapidly depreciate the satisfactions of property. Of the hunter it is truly said that his wealth is a burden. In his condition of life, goods can become "grievously oppressive", as Gusinde observes, and the more so the longer they are carried around. Certain food collectors do have canoes and a few have dog sleds, but most must carry themselves all the comforts they possess, and so only possess what they can comfortably carry themselves. Or perhaps only what the women can carry: the men are often left free to reach to the sudden opportunity of the chase or the sudden necessity of defence. As Owen Lattimore wrote in a not too different context, "the pure nomad is the poor nomad". Mobility and property are in contradiction. That wealth quickly becomes more of an encumbrance than a good thing is apparent even to the outsider. Laurens van der Post (11) was caught in the contradiction as he prepared to make farewells to his wild Bushmen friends: "This matter of presents gave us many an anxious moment. We were humiliated by the realisation of how little there was we could give to the Bushmen. Almost everything seemed likely to make life more difficult for them by adding to the litter and weight of their daily round. They themselves had practically no possessions: a loin strap, a skin blanket and a leather satchel. There was nothing that they could not assemble in one minute, wrap up in their blankets and carry on their shoulders for a journey of a thousand miles. They had no sense of possession." Here then is another economic "peculiarity"- some hunters at least, display a notable tendency to be sloppy about their possessions. They have the kind of nonchalance that would be appropriate to a people who have mastered the problems of production. "They do not know how to take care of their belongings. No one dreams of putting them in order, folding them, drying or cleaning them, hanging them up, or putting them in a neat pile. If they are looking for some particular thing, they rummage carelessly through the hodgepodge of trifles in the little baskets. Larger objects that are piled up in a heap in the hut are dragged hither and thither with no regard for the damage that might be done them. The European observer has the impression that these (Yahgan) Indians place no value whatever on their utensils and that they have completely forgotten the effort it took to make them. Actually, no one clings to his few goods and chattels which, as it is, are often and easily lost, but just as easily replaced... The Indian does not even exercise care when he could conveniently do so. A European is likely to shake his head at the boundless indifference of these people who drag brand-new objects, precious clothing, fresh provisions and valuable items through thick mud, or abandon them to their swift destruction by children and dogs.... Expensive things that are given them are treasured for a few hours, out of curiosity; after that they thoughtlessly let everything deteriorate in the mud and wet. The less they own, the more comfortable they can travel, and what is ruined they occasionally replace. Hence, they are completely indifferent to any material possessions."(10) The hunter, one is tempted to say, is "uneconomic man". At least as concerns non subsistence goods, he is the reverse of that standard caricature immortalised in any General Principles of Economics, page one. His wants are scarce and his means (in relation) plentiful. Consequently he is "comparatively free of material pressures", has "no sense of possession", shows "an undeveloped sense of property", is "completely indifferent to any material pressures", manifests a "lack of interest" in developing his technological equipment. In this relation of hunters to worldly goods there is a neat and important point. From the internal perspective of the economy, it seems wrong to say that wants are "restricted", desires "restrained", or even that the notion of wealth is "limited". Such phrasings imply in advance an Economic Man and a struggle of the hunter against his own worse nature, which is finally then subdued by a cultural vow of poverty. The words imply the renunciation of an acquisitiveness that in reality was never developed, a suppression of desires that were never broached. Economic Man is a bourgeois construction- as Marcel Mauss said, "not behind us, but before, like the moral man". It is not that hunters and gatherers have curbed their materialistic "impulses"; they simply never made an institution of them. "Moreover, if it is a great blessing to be free from a great evil, our (Montagnais) Savages are happy; for the two tyrants who provide hell and torture for many of our Europeans, do not reign in their great forests, I mean ambition and avarice... as they are contented with a mere living, not one of them gives himself to the Devil to acquire wealth."(12) Subsistence When Herskovits (13) was writing his Economic Anthropology (1958), it was common anthropological practice to take the Bushmen or the native Australians as "a classic illustration; of a people whose economic resources are of the scantiest", so precariously situated that "only the most intense application makes survival possible". Today the "classic" understanding can be fairly reversed- on evidence largely from these two groups. A good case can be made that hunters and gatherers work less than we do; and, rather than a continuous travail, the food quest is intermittent, leisure abundant, and there is a greater amount of sleep in the daytime per capita per year than in any other condition of society. The most obvious, immediate conclusion is that the people do not work hard. The average length of time per person per day put into the appropriation and preparation of food was four or five hours. Moreover, they do not work continuously. The subsistence quest was highly intermittent. It would stop for the time being when the people had procured enough for the time being. which left them plenty of time to spare. Clearly in subsistence as in other sectors of production, we have to do with an economy of specific, limited objectives. By hunting and gathering these objectives are apt to be irregularly accomplished, so the work pattern becomes correspondingly erratic. As for the Bushmen, economically likened to Australian hunters by Herskovits, two excellent recent reports by Richard Lee show their condition to be indeed the same 14 16 Lee's research merits a special hearing not only because it concerns Bushmen, but specifically the Dobe section of Kung Bushmen, adjacent to the Nyae about whose subsistence- in a context otherwise of "material plenty"- Mrs Marshall expressed important reservations. The Dobe occupy an area of Botswana where !Kung Bushmen have been living for at least a hundred years, but have only just begun to suffer dislocation pressures. Abundance Despite a low annual rainfall (6 to 10 inches), Lee found in the Dobe area a "surprising abundance of vegetation". Food resources were "both varied and abundant", particularly the energy rich mangetti nut- "so abundant that millions of the nuts rotted on the ground each year for want of picking".15 The Bushman figures imply that one man's labour in hunting and gathering will support four or five people. Taken at face value, Bushman food collecting is more efficient than French farming in the period up to World War II, when more than 20 per cent of the population were engaged in feeding the rest. Confessedly, the comparison is misleading, but not as misleading as it is astonishing. In the total population of free-ranging Bushmen contacted by Lee, 61.3 per cent (152 of 248) were effective food producers; the remainder were too young or too old to contribute importantly In the particular camp under scrutiny, 65 per cent were "effectives". Thus the ratio of food producers to the general population is actually 3 :5 or 2:3. But, these 65 per cent of the people "worked 36 per cent of the time, and 35 per cent of the people did not work at all"! (15) For each adult worker, this comes to about two and one - half days labour per week. (In other words, each productive individual supported herself or himself and dependents and still had 3 to 5 days available for other activities.) A "day's work" was about six hours; hence the Dobe work week is approximately 15 hours, or an average of 2 hours 9 minutes per day. All things considered, Bushmen subsistence labours are probably very close to those of native Australians. Also like the Australians, the time Bushmen do not work in subsistence they pass in leisure or leisurely activity. One detects again that characteristic palaeolithic rhythm of a day or two on, a day or two off- the latter passed desultorily in camp. Although food collecting is the primary productive activity, Lee writes, "the majority of the people's time (four to five days per week) is spent in other pursuits, such as resting in camp or visiting other camps" (15): "A woman gathers on one day enough food to feed her family for three days, and spends the rest of her time resting in camp, doing embroidery, visiting other camps, or entertaining;n; visitors from other camps. For each day at home, kitchen routines, such as cooking, nut cracking, collecting firewood, and fetching water, occupy one to three hours of her time. This rhythm of steady work and steady leisure maintained throughout the year. The hunters tend to work more frequently than the women, but their schedule uneven. It 'not unusual' for a man to hunt avidly for a week and then do no hunting at all for two or three weeks. Since hunting is an unpredictable business and su bject to magical control, hunters sometimes experience a run of bad luck and stop hunting for a month or longer. During these periods, visiting, entertaining, and especially dancing are the primary activities of men.(16)" The daily per-capita subsistence yield for the Dobe Bushmen was 2,140 calories. However, taking into account body weight, normal activities, and the age-sex composition of the Dobe population, Lee estimates the people require only 1,975 calories per capita. Some of the surplus food probably went to the dogs, who ate what the people left over. "The conclusion can be drawn that the Bushmen do not lead a substandard existence on the edge of starvation as has been commonly supposed."(15) Meanwhile, back in Africa the Hadza have been long enjoying a comparable ease, with a burden of subsistence occupations no more strenuous in hours per day than the Bushmen or the Australian Aboriginals.16 Living in an area of "exceptional abundance" of animals and regular supplies of vegetables (the vicinity of Lake Eyasi), Hadza men seem much more concerned with games of chance than with chances of game. During the long dry season especially, they pass the greater part of days on end in gambling, perhaps only to lose the metal-tipped arrows they need for big game hunting at other times. In any case, many men are "quite unprepared or unable to hunt big game even when they possess the necessary arrows". Only a small minority, Woodburn writes, are active hunters of large animals, and if women are generally more assiduous at their vegetable collecting, still it is at a leisurely pace and without prolonged labour.(17) Despite this nonchalance, and an only limited economic cooperation, Hadza "nonetheless obtain sufficient food without undue effort". Woodburn offers this "very rough approximation" of subsistence-labour requirements: "Over the year as a whole probably an average of less than two hours a day spent obtaining food" (Woodburn.16) Interesting that the Hazda, tutored by life and not by anthropology, reject the neolithic revolution in order to keep their leisure. Although surrounded by cultivators, they have until recently refused to take up agriculture themselves, "mainly on the grounds that this would involve too much hard work". In this they are like the Bushmen, who respond to the neolithic question with another: "Why should we plant, when there are so many mongomongo nuts m the world?" (14) Woodburn moreover did form the impression, although as yet unsubstantiated, that Hadza actually expend less energy, and probably less time, obtaining subsistence than do neighbouring cultivators of East Africa. (16) To change continents but not contents, the fitful economic commitment of the South American hunter, too, could seem to the European outsider an incurable "natural disposition": "... the Yamana are not capable of continuous, daily hard labour, much to the chagrin of European farmers and employers for whom they often work. Their work is more a matter of fits and starts, and in these occasional efforts they can develop considerable energy for a certain time. After that, however, they show a desire for an incalculably long rest period during which they lie about doing nothing, without showing great fatigue.... It is obvious that repeated irregularities of this kind make the European employer despair, but the Indian cannot help it. It is his natural disposition." (10) The hunter's attitude towards farming introduces us, lastly, to a few particulars of the way they relate to the food quest. Once again we venture here into the internal realm of the economy, a realm sometimes subjective and always difficult to understand; where, moreover, hunters seem deliberately inclined to overtax our comprehension by customs so odd as to invite the extreme interpretation that either these people are fools or they really have nothing to worry about. The former would be a true logical deduction from the hunter's nonchalance, on the premise that his economic condition is truly exigent. On the other hand, if a livelihood is usually easily procured, if one can usually expect to succeed, then the people's seeming imprudence can no longer appear as such. Speaking to unique developments of the market economy, to its institutionalisation of scarcity, Karl Polanyi (18) said that our "animal dependence upon food has been bared and the naked fear of starvation permitted to run loose. Our humiliating enslavement to the material, which all human culture is designed to mitigate, was deliberately made more rigorous" But our problems are not theirs. Rather, a pristine affluence colours their economic arrangements, a trust in the abundance of nature's resources rather than despair at the inadequacy of human means. My point is that otherwise curious heathen devices become understandable by the people's confidence, a confidence which is the reasonable human attribute of a generally successful economy. A more serious issue is presented by the frequent and exasperated observation of a certain "lack of foresight" among hunters and gatherers. Orientated forever in the present, without "the slightest thought of, or care for, what the morrow may bring", (19) the hunter seems unwilling to husband supplies, incapable of a planned response to the doom surely awaiting him. He adopts instead a studied unconcern, which expresses itself in two complementary economic inclinations. The first, prodigality: the propensity to eat right through all the food in the camp, even during objectively difficult times, "as if", Lillian said of the Montagnais, "the game they were to hunt was shut up in a stable". Basedow (20) wrote of native Australians, their motto "might be interpreted in words to the effect that while there is plenty for today never care about tomorrow. On this account an Aboriginal inclined to make one feast of his supplies, in preference to a modest meal now and another by and by." Le Jeune even saw his Montagnais carry such extravagance to the edge of disaster. "In the famine through which we passed, if my host took two, three, or four Beavers, immediately, whether it was day or night, they had a feast for all neighbouring Savages. And if those People had captured something, they had one also at the same time; so that, on emerging from one feast, you went to another, and sometimes even to a third and a fourth. I told them that they did not manage well, and that it would be better to reserve these feasts for future days, and in doing this they would not be so pressed with hunger. They laughed at me. 'Tomorrow' (they said) 'we shall make another feast with what we shall capture.' Yes, but more often they capture only cold and wind." (12) A second and complementary inclination is merely prodigality's negative side: the failure to put by food surpluses, to develop food storage. For many hunters and gatherers, it appears, food storage cannot be proved technically impossible, nor is it certain that the people are unaware of the possibility. (18) One must investigate instead what in the situation precludes the attempt. Gusinde asked this question, and for the Yahgan found the answer in the self same justifiable optimism. Storage would be "superfluous", "because through the entire year and with almost limitless generosity the she puts all kinds of animals at the disposal of the man who hunts and the woman who gathers. Storm or accident will deprive a family of these things for no more than a few days. Generally no one need reckon with the danger of hunger, and everyone almost any where finds an abundance of what he needs. Why then should anyone worry about food for the future... Basically our Fuegians know that they need not fear for the future, hence they do not pile up supplies. Year in and year out they can look forward to the next day, free of care...." (12) Gusinde's explanation is probably good as far as it goes, but probably incomplete. A more complex and subtle economic calculus seems in play. In fact one must consider the advantages of food storage against the diminishing returns to collection within a confined locale. An uncontrollable tendency to lower the local carrying capacity is for hunters au fond des choses: a basic condition of their production and main cause of their movement. The potential drawback of storage is exactly that it engages the contradiction between wealth and mobility. It would anchor the camp to an area soon depleted of natural food supplies. Thus immobilised by their accumulated stocks, the people may suffer by comparison with a little hunting and gathering elsewhere, where nature has, so to speak, done considerable storage of her own-of foods possibly more desirable in diversity as well as amount than men can put by. As it works out, an attempt to stock up food may only reduce the overall output of a hunting band, for the havenots will content themselves with stay- ing in camp and living off !he wherewithal amassed by the more prudent. Food storage, then, may be technically feasible, yet economically undesirable, and socially unachievable. What are the real handicaps of the hunting-gathering praxis? Not "low productivity of labour", if existing examples mean anything. But the economy is seriously" afflicted by the imminence of diminishing returns. Beginning in subsistence and spreading from there to every sector, an initial success seems only to develop the probability that further efforts will yield smaller benefits. This describes the typical curve of foodgetting within a particular locale. A modest number of people usually sooner than later reduce the food resources within convenient range of camp. Thereafter, they may stay on only by absorbing an increase in real costs or a decline in real returns: rise in costs if the people choose to search farther and farther afield, decline in returns if they are satisfied to live on the shorter supply or inferior foods in easier reach. The solution, of course, is to go somewhere else. Thus the first and decisive contingency of hunting-gathering: it requires movement to maintain production on advantageous terms. But this movement, more or less frequent in different circumstances, more or less distant. merely transposes to other spheres of production the same diminishing returns of which it is born. The manufacture of tools, clothing, utensils, or ornaments, how- ever easily done, becomes senseless when these begin to be more of a burden than a comfort Utility falls quickly at the margin of portability. The construction of substantial houses likewise becomes absurd if they must soon be abandoned. Hence the hunter's very ascetic conceptions of material welfare: an interest only in minimal equipment, "if that; a valuation of smaller things over bigger; a disinterest in acquiring two or more of most goods; and the like. Ecological pressure assumes a rare form of concreteness when it has to be shouldered. If the gross product is trimmed down in comparison with other economies, it is not the hunter's productivity that is at fault, but his mobility. Demographic constraints Almost the same thing can be said of the demographic constraints of huntinggathering. The same policy of debarassment is in play on the level of people, describable in similar terms and ascribable to similar causes. The terms are, coldbloodedly: diminishing returns at the margin of portability, minimum necessary equipment, elimination of duplicates, and so forth-that is to say, infanticide. senilicide, sexual continence for the duration of the nursing period, etc., practices for which many food-collecting peoples are well known. The presumption that such devices are due to an inability to support more people is probably true-if' "support" is understood in the sense of carrying them rather than feeding them. The people eliminated, as hunters sometimes sadly' tell, are precisely those who cannot effectively transport themselves, who would I hinder the movement of family and camp. Hunters may be obliged to handle people and goods in parallel ways, the draconic population policy an expression of the same ecology as the ascetic economy. Hunting and gathering has all the strengths of its weaknesses. Periodic movement and restraint in wealth and adaptations, the kinds of necessities of the economic practice and creative adaptations the kinds of necessities of which virtues are made. Precisely in such a framework, affluence becomes possible. Mobility and moderation put hunters' ends within range of their technical means. An undeveloped mode of production is thus rendered highly effective. The hunter's life is not as difficult as it looks from the outside. In some ways the economy reflects dire ecology, but it is also a complete inversion. Three to five hour working day Reports on hunters and gatherers of the ethnological present-specifically on those in marginal environments suggest a mean of three to five hours per adult worker per day in food production. Hunters keep banker's hours, notably less than modern industrial workers (unionised), who would surely settle for a 21-35 hour week. An interesting comparison is also posed by recent studies of labour costs among agriculturalists of neolithic type. For example, the average adult Hanunoo, man or woman, spends 1,200 hours per year in swidden cultivation;21 which is to say, a mean of three hours twenty minutes per day. Yet this figure does not include food gathering, animal raising, cooking and other direct subsistence efforts of these Philippine tribesmen. Comparable data are beginning to appear in reports on other primitive agriculturalists from many parts of the world. There is nothing either to the convention that hunters and gatherers can enjoy little leisure from tasks of sheer survival. By this, the evolutionary inadequacies of the palaeolithic are customarily explained, while for the provision of leisure the neolithic is roundly congratulated. But the traditional formulas might be truer if reversed: the amount of work (per capita) increases with the evolution of culture, and the amount of leisure decreases. Hunter's subsistence labours are characteristically intermittent, a day on and a day off, and modern hunters at least tend to employ their time off in such activities as daytime sleep. In the tropical habitats occupied by many of these existing hunters, plant collecting is more reliable than hunting itself. Therefore, the women, who do the collecting, work rather more regularly than the men, and provide the greater part of the food supply. In alleging this is an affluent economy, therefore, I do not deny that certain hunters have moments of difficulty. Some do find it "almost inconceivable" for a man to die of hunger, or even to fail to satisfy his hunger for more than a day or two.16 But others, especially certain very peripheral hunters spread out in small groups across an environment of extremes, are exposed periodically to the kind of inclemency that interdicts travel or access to game. They suffer although perhaps only fractionally, the shortage affecting particular immobilised families rather than the society as a whole. (10) Still, granting this vulnerability, and allowing the most poorly situated modern hunters into comparison. it would be difficult to prove that privation is distinctly characteristic of the hunter-gatherers. Food shortage is not the indicative property of this mode of production as opposed to others; it does not mark off hunters and gatherers as a class or a general evolutionary stage. Lowie (22) asks: "But what of the herders on a simple plane whose maintenance is periodically jeopardised by plagues-who, like some Lapp bands of the nineteenth century were obliged to fall back on fishing? What of the primitive peasants who clear and till without compensation of the soil, exhaust one plot and pass on to the next, and are threatened with famine at every drought? Are they any more in control of misfortune caused by natural conditions than the hunter-gatherer?" Above all. what about the world today? One-third to one-half of humanity are said to go to bed hungry every night. In the Old Stone Age the fraction must have been much smaller. This is the era of hunger unprecedented. Now, in the time of the greatest technical power, is starvation an in. situation. Reverse another venerable formula: the amount of hunger in. creases relatively and absolutely with the evolution of culture. This paradox is my whole point. Hunters and gatherers have by force of circumstances an objectively low standard of living. But taken as their objective, and given their adequate means of production. all the people's material wants usually can be easily satisfied. The world's most primitive people have few possessions. but they are not poor. Poverty is not a certain small amount of goods, nor is it just a relation between means and ends; above all it is a relation between people. Poverty is a social status. As such it is the invention of civilisation. It has grown with civilisation, at once as an invidious distinction between classes and more importantly as a tributary relation that can render agrarian peasants more susceptible to natural catastrophes than any winter camp of Alaskan Eskimo. References 1. Lowie, Robert H; 1946 An introduction to Cultural Anthropology (2nd ed.) New York. Rinehart. 2. Braidwood, Robert J. 1957. Prehistoric Men. 3rd ed. Chicago Natural History Museum Popular Series, Anthrpology, Number 37. 3. Braidwood; Robert J. 1952. The Near East and the Foundations for Civilisation. Eugene: Oregon State System of Higher Education. 4. Boas, Franz. 1884-85. "The Central Eskimo", Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology, Anthropological Reports 6: 399=699. 5. White, Leslie A. 1949. The Science of Culture. New York: Farrar, Strauss. 6. White, Leslie A. 1959. The Evolution of Culture. New York: McGraw-Hill. 7. Grey, Sir George. 1841. Journals of Two Expeditions of Discovery in North-West and Western Australia, During the Years 1837, 38, and 39... 2 vols. London: Boone. 8. Eyre, Edward John. 1845. Journals of Expeditions of Discovery into Central Australia, and Overland from Adelalde to King George's Sound, in the Years 184041.2 vols. London: Boone. 9. Marshall, Lorna. 1961. "Sharing, Talking, and Giving: Relief of Social Tensions Among "Kung Bushmen", Africa 31:23149. 10. Gusinde, Martin. 1961. The Yamana 5 vols. New Haven, Conn.: Human Relations Area Files. (German edition 1931). 11. Laurens van der Post: The Heart of the Hunter. 12. Le Jeune, le Pere Paul. 1897. "Relation of What Occured in New France in the Year 1634", in R. G. Thwaites (ed.), The Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents. Vol. 6. Cleveland: Burrows. (First French edition, 1635). 13. Herskovits, Melville J. 1952. Economic Anthropology. New York: Knopf. 14. Lee, Richard. 1968. "What Hunters Do for a Living, or, How to Make Out on Scarce Resources", in R. Lee and I. DeVore (eds.), Man the Hunter. Chicago: Aldine. 15. Lee, Richard. 1969. "Kung Bushmen Subsistence: An Input-Output Analysis", in A. Vayda (ed.), Environment and Cultural Behaviour. Garden City, N.Y.: Natural History Press. 16. Woodburn, James. 1968. "An introduction to Hadza Ecology", in Lee and I. DeVore (eds.), Man the Hunter. Chicago: Aldine. 17. Woodburn, James (director). 1966: "The Hadza" (film available from the anthropological director, department of Anthropology, London School of Economics). 18. Polanyi, Karl. 1974. "Our Obsolete Market Mentality", Commentary 3:109-17. 19. Spencer, Baldwin, and F. J. Gillen, 1899. The Native Tribes of Central Australia London: Macmillan. 20. Basedow, Herbert. 1925. The Australian Aboriginal. Adelaide, Australia: Preece. 21. Conklin, Harold C. 1957. Hanunoo Agriculture. Rome: Food and Agricultural Organisation of the United Nations. 22. Lowie, Robert H. 1938. "Subsistence", in F. Boas (ed.), General Anthropology. (2nd ed.) New York: Rinehart. Extract from stone-age Economics. By Marshall Sahlins