Middle Ages - Lesson # 3 Religion & Politics

advertisement

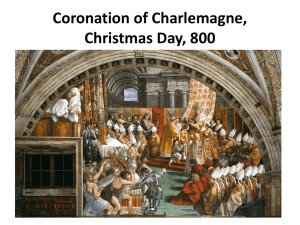

The Power of the Church Religion in the Middle Ages bishops actually made most important religious decisions. As a result, the papacy was not held in high regard. Adding to this lack of esteem was the fact that few popes during this time were noted for their religious devotion. Most of them were nobles who were more concerned with increasing their own power than overseeing spiritual matters. The pope is the head of the Roman Catholic Church. Early popes were seen as spiritual leaders, but during the Middle Ages they became powerful political figures as well. How did this change come about? In 1049 the first of series of clever and capable popes dedicated to reforming the papacy came to power. His name was Leo IX. A man of high ideals, Leo believed that Europe’s clergy had become corrupt and set out on a mission to reform it. Among Leo’s top concerns was simony, the buying and selling of church offices. He traveled throughout Europe, seeking out and replacing bishops suspected of such offenses. While manorialism and feudalism encouraged local loyalties, Christian beliefs brought people across Europe together in the spiritual community of Christendom. The majority of people in Europe were, at least in name, Christian, and religion touched almost every aspect of their lives. Major events – baptism, marriage, death – were marked by religious ceremonies. Monks acted as peacemakers in disputes and prayed for the safety of rulers and armies. Church officials also served as teachers and record keepers. As the people’s main connection to the church, members of the clergy had great influence. Bishops guilty of particularly bad offenses were excommunicated, or cast out of the church. For Christians in the Middle Ages, there was no greater punishment. A person who had been excommunicated could not take part in the Eucharist, and the believe was that one who died while excommunicated would not be saved. Through his reforms, Leo became more active in governing the church than any other pope had been for centuries. Sometime around 1000 AD the influence of the church increased dramatically. At that time, there was a great upwelling of piety in Europe. Piety is a person’s level of devotion to his or her religion. For centuries Europeans had been members of the Christian church, but at this time many believers became more devout. Across Europe, people’s participation in religious services increased, and thousands flocked to monasteries to join religious orders. Task: Write a two-sentence summary of Religion in the Middle Ages. Growth of Papal Power The common people of Europe were not the only ones inspired by a new sense of piety in the Middle Ages. Within the Christian Church itself, many clergy members sought ways to improve conditions and end corrupt practices. Church Reforms In the 900s and 1000s, popes had little authority. Although the pope was considered the head of the entire church, local Leo’s reforms brought him into conflict with both political and religious leaders. Kings resented what they saw an interference with the bishops in their kingdoms. Many bishops, too, believed the pope had no authority to tell them how to act. Among those who rejected Leo’s authority was the patriarch, or bishop, of Constantinople. Leo excommunicated the patriarch in 1054, an action that split the Christian Church in two. Those who agreed with Leo were Roman Catholic, and those who sided with the patriarch were called Orthodox. Popes and Politics Popes gained influence not only over people’s religious lives but also over politics in Europe. The pope became the head of a huge network of ecclesiastical, or church, courts that heard cases on religious or moral matters. Popes also ruled territories, such as the Papal States in Italy. To defend their territories, popes had the ability to raise armies. For example, several popes hired the Normans to fight wars on their behalf. The Crusades, a series of wars launched against the Muslims of Southwest Asia, were launched by popes. Conflict over Bishops Although popes had increased their power, they still came into conflict with political leaders. Popes of the late 1000s were firmly resolved to change the way members of the clergy were chosen. For years, kings and other leaders had played an active role in choosing clergy. Kings chose most of the bishops who served in their lands, and the Holy Roman Emperor had named several popes. The reform popes did not think that anyone except the clergy should choose religious officials. The issue of clergy selection became critical during the pontificate, or papal term in office, of Pope Gregory VII in the late 1000s. At that time, the Holy Roman Emperor was Henry IV. In 1075, Henry chose a new bishop for the city of Milan in northern Italy. Gregory did not approve of his choice and removed the bishop. In response, Henry wrote a scathing letter to the pope, stating that Gregory had no authority over him or any other ruler. Gregory’s response was to excommunicated Henry. He also called on the clergy and nobility of Germany to replace the emperor with a more suitable candidate. This response frightened Henry. Fearing that he would lose his throne, he traveled to Canossa, Italy, where Gregory was staying to beg forgiveness. Though reluctant, Gregory lifted the excommunication. Gregory and Henry continued to fight over bishops for years. In fact, the conflict over this issue outlived both men. Later popes and emperors finally reached a compromise: local clergy would choose bishops, but their choices could be vetoed by secular rulers. More important than the details of the conflict, though, was the fact that Gregory had been able to stand up to the emperor. The pope had become one of the strongest figures in Europe. Task: Draw a diagram of your choice to explain the role of the pope and his influence of people and politics in Europe. Changes in Monasticism In the early Middle Ages, monasteries had been founded all across Europe by men seeking lives of contemplation and prayer. These monasteries were often paid for by local rulers, who then helped to choose the abbots who led the monasteries. By about 900, however, rulers had stopped choosing qualified abbots. Far from beign religious, many abbots held their positions just for the prestige it brought to them or their families. In monasteries led by these abbots, the strict Benedictine Rule was largely abandoned. In the early 900s, a small group of monks sought to return monasticism to its strict roots. They established a new monastery at Cluny, France, where they would live strictly according to the Benedictine Rule. To prevent the onset of corruption, the monks of Cluny reserved the right to choose their own abbot, rather than having one appointed to them. Over time, Cluny became the most influential monastery in Europe. Monks from Cluny established daughter houses, whose leaders had to answer to the abbot of Cluny. In addition, other monasteries in France, Spain and Italy adopted Cluny’s customs and agreed to follow the direction of its abbots. Eventually, Cluny became the core of a network of monasteries that stretched across western Europe. For some monks, however, even the Benedictine life was not strict enough. These monks wanted lives free from any worldly distractions. Not finding what they wanted in Benedictine houses, they created new orders. The most popular of these new monastic orders was the Cistercian order. Cistercian monasteries were usually broad estates built outside of towns to ensure isolation. These monasteries were undecorated and unheated, even in winter. The monks who lived their divided their time between prayer and labor, such as farm work or copying texts (bibles). Some other new orders were even stricter than the Cistercians. Members of these orders lived like hermits in tiny cells, having no contact with other people. Those who joined such orders were widely admired for their piety and dedication to their faith. Task: write as many questions as possible about the reading (as if you were writing the questions Criteria: Questions must have provable answer Must write questions and answer on their own sheet Minimum: 15 questions CHARLEMAGNGE Instructions: Answer all italicized questions at the end of each paragraph. The Frankish Mayors of the Palace represented a new aristocracy -- the class of warriors. This class attained its wealth solely from land. Frankish culture was not urban and as a result in the early Middle Ages we see a general decline of urban life not to be revived into well after the 12th century. In your notebook, identify how wealth was accumulated during this time period. It has been said that it was during the reign of CHARLEMAGNE (742-814) that the transition from classical to early medieval civilization was completed. He came to the throne of the Frankish kingdom in 771 and ruled until 814. His reign spans more than 40 years and it was during this time that a new civilization -- a European civilization -came into existence. If anything characterizes Charlemagne's rule it was stability. His reign was based on harmony which developed between three elements: the Roman past, the Germanic way of life, and Christianity. Charlemagne devoted his entire reign to blending these three elements into one kingdom and by doing this, he secured a foundation upon which European society would develop. What impact would a 40-year rule have on an Emperor’s ability to create an empire and make changes? Frankish society was entirely rural and was composed of three classes or orders: (1) the peasants - those who work, (2) the nobility - those who fight, and, (3) the clergy those who pray. In general, life was brutal and harsh for the early medieval peasant. Even in the wealthiest parts of Europe, the story is one of poverty and hardship. Their diet was poor and many peasants died undernourished. Most were illiterate although a few were devout Christians. The majority could not understand Latin, the language of the Church. The nobility were better off. Their diet, although they had more food, was still not very nutritional. They lived in larger houses than the peasants but their castles were often just as cold as the peasant's small hut. Furthermore, most of nobility were illiterate and crude. They spent most of their time fighting. Their religious beliefs were, for the most part, similar to those of the peasants. At the upper level were the clergy. They were the most educated and perhaps the only people to truly understand Christianity since they were the only people who had access to the Bible. It was the clergy who held a monopoly on knowledge, religious beliefs and religious practice. Why was life difficult for peasants? Think specifically to how it differs from life today in terms of quality of life. When Charlemagne took the throne in 771, he immediately implemented two policies. The first policy was one of expansion. Charlemagne's goal was to unite all Germanic people into one kingdom. The second policy was religious in that Charlemagne wanted to convert all of the Frankish kingdom, and those lands he conquered, to Christianity. As a result, Charlemagne's reign was marked by almost continual warfare. Why was it important to unite and convert? Because Charlemagne's armies were always fighting, he began to give his warriors land so they could support and equip themselves. With this in mind, Charlemagne was able to secure an army of warriors who were deeply devoted and loyal to him. By the year 800, the Frankish kingdom included all of modern France, Belgium, Holland, Switzerland, almost all of Germany and large areas of Italy and Spain. It seemed clear that Charlemagne was yet another Constantine, perhaps even another Augustus Caesar. What was the significance of giving his warriors land? Toward the end of the year 800, Pope Leo III asked Charlemagne to come to Rome. On Christmas Day Charlemagne attended mass at St. Peters. When he finished his prayers, Pope Leo prostrated himself before Charlemagne and then placed a crown upon his head. Pope Leo then said "life and victory to Charles Augustus, crowned by God, the great and peaceful emperor of the Romans." This was an extremely important act. Charlemagne became the first emperor in the west since the last Roman emperor was deposed in 476. Charlemagne's biographer, Einhard (c.770-840), has recorded that Charlemagne was not very much interested in Pope Leo's offering. Had Charlemagne known what was to happen on that Christmas day, he never would have attended the mass. The bottom line is this -- Charlemagne had no intention of being absorbed into the Roman Church. From the point of view of Pope Leo, the CORONATION OF CHARLEMAGNE signified the Pope's claim to dispense the imperial crown. It was Leo's desire to assert papal supremacy over a unified Christendom and he did this by coronating Charlemagne. Why did the Pope crown Charlemagne? What was the significance of how Charlemagne was crowned? Who has more power: the church or the crown? By gaining the imperial title, Charlemagne received no new lands. He never intended to make Rome the center of his empire. In fact, from Christmas Day 800 to his death in 814, Charlemagne never returned to Rome. Instead, Charlemagne returned to France as emperor and began a most effective system of rule. He divided his kingdom into several hundred counties or administrative units. Along the borders of the kingdom, Charlemagne appointed military governors. To insure that this system worked effectively, Charlemagne sent out messengers (missi domini), one from the church and one lay person, to check on local affairs and report directly to him. Charlemagne also traveled freely throughout his kingdom in order to make direct contact with his people. This was in accordance with the German tradition of maintaining loyalty. He could also supervise his always troublesome nobility and maintain the loyalty of his subjects. There was no fixed capital but Charlemagne spent most of his time at Aachen. Based on this passage, what qualities did Charlemagne possess that made him a strong leader? In terms of commerce, Charlemagne standardized the minting of coins based on the silver standard. This also actively encouraged trade, especially in the North Sea. The Franks manufactured swords, pottery and glassware in northern France which they exported to England, Scandinavia and the Lowlands. He also initiated trade between the Franks and the Muslims and made commercial pacts with the merchants of Venice who traded with both Byzantium and Islam. Why is it important to trade with different cultures? The most durable and significant of all Charlemagne's efforts was the revival of learning in his kingdom. This was especially so among the clergy, many of whom were barely literate. On the whole, the monks were not much better educated. Even those monks who spent their days copying manuscripts could barely read or understand them. The manuscripts from the 7th and 8th centuries were confusing. They were all written in uppercase letters and without punctuation. There were many errors made in copying and handwriting was poor. There were, however, a few educated monks as well as the beginnings of a few great libraries. But Charlemagne could not find one good copy of the Bible, nor a complete text of the Benedictine Rule. He had to send to Rome for them. Above all, Charlemagne wanted unity in the Frankish Church, a Church wholly under his supervision. Charlemagne, although illiterate as a youth, was devoted to new ideas and to learning. He studied Latin, Greek, rhetoric, logic and astronomy. He wanted to meet an educated man -- he was very lucky. He was in northern Italy when he met the Anglo-Saxon scholar, Alcuin. “The most durable and significant of all Charlemagne’s efforts was the revival of learning in his kingdom” – why was literacy important? Why was this his number one goal? By the 9th century, most monasteries had writing rooms or scriptoria. It was here that manuscripts were copied. The texts were studied with care. It was no longer merely a matter of copying texts. It was now first necessary to correct any mistakes which had been made over years of copying. Copying was indeed difficult: lighting was poor, the monk's hands were cramped by cold weather and there was no standard scholarly language. What Charlemagne did was institute a standard writing style. Remember, previous texts were all uppercase, without punctuation and there was no separation between words. The letters of the new script, called the Carolingian minuscule, were written in upper and lower case, with punctuation and words were separated. It should be obvious that this new script was much easier to read, in fact, it is the script we use today. Charlemagne also standardized medieval Latin. After all, much had changed in the Latin language over the past 1000 years. New words, phrases, and idioms had appeared over the centuries in these now had to be incorporated into the language. So what Charlemagne did was take account of all these changes and include them in a new scholarly language which we know as medieval Latin. Why is it important to make writing, reading and speaking more uniform? One of the most important consequences of the Carolingian Renaissance was that Charlemagne encouraged the spread of uniform religious practices as well as a uniform culture. Charlemagne set out to construct a respublica Christiana, a Christian republic. Despite the fact that Charlemagne unified his empire, elevated education, standardized coins, handwriting and even scholarly Latin, his Empire declined in strength within a generation or two following his death in the year 814. His was a hard act to follow. His rule was so brilliant, so superior, that those emperors who came after him seemed inferior. We've seen this before with Alexander the Great, Augustus Caesar, Constantine, Justinian and Mohammed. Why was Charlemagne a hard act to follow? Although the Frankish kingdom went into decline, the death of Charlemagne was only one cause of the decline. We must consider the renewed invasions from barbarian tribes. The Muslims invaded Sicily in 827 and 895, invasions which disrupted trade between the Franks and Italy. The Vikings came from Denmark, Sweden and Norway and invaded the Empire in the 8th and 9th centuries. The Danes attacked England, and northern Gaul. The Swedes attacked areas in central and eastern Europe and Norwegians attacked England, Scotland and Ireland and by the 10th century, had found their way to Greenland. The third group of invaders were the Magyars who came from modern-day Hungary. Their raids were so terrible that European peasants would burn their fields and destroy their villages rather than give them over. All these invasions came to an end by the 10th and 11th centuries for the simple reason that these tribes were converted to Christianity. And it would be the complex institution known as feudalism which would offer Europeans protection from these invasions, based as it was on security, protection and mutual obligations. What were the contributing factors leading to the demise of Charlemagne’s empire? The Christian Religion The Christian religion, or Christianity, is the name given to the system of religious beliefs and practices which incorporates the teachings of Jesus of Nazareth from the region of Palestine during the reign of the Roman Emperor Tiberius (42 BC - AD 37). Christianity took its rise in Judaism. Jesus of Nazareth, its founder, and his disciples were all orthodox Jews. The new Christian religion emerged based on the testimony found in the New Testament of the Bible, as interpreted by the life of Jesus and the teachings of his apostles. Christianity began among a small number of Jews. Christianity was seen as a threat to the Roman Empire as Christians refused to worship the Roman gods or the Emperor. This resulted in the persecution of the early Christians, many of whom were killed and thus became martyrs of the Christian religion. The persecution of adherents to the Christian religion ended during the reign of the Roman Emperor Constantine. Emperor Constantine I (AD ca. 285 - AD 337) of the Roman Empire legalized Christianity and proclaimed himself as an 'Emperor of the Christian people'. Most of the Roman Emperors that came after Constantine were Christians. Christianity then became the official religion of the Roman Empire, instead of the old Roman religion that had worshipped many Gods. In the 5th century, the Western Roman Empire began to crumble. Germanic tribes (barbarians) conquered the city of Rome. This event started the period in medieval history commonly referred to as the Dark Ages. The period of the Dark Ages saw the growth in the power of the Church. The only accepted interpretation of Christianity in western Europe was the Catholic tradition. The word Catholic derives from the Latin word 'catholicus,' meaning universal or whole. Any other sects were viewed as heretical, whereas the Catholic tradition was seen as the true Christian Church. With its own laws and lands, the Catholic Church was a very powerful institution. The Catholic Church also imposed taxes in the form of tithing. In addition to, the Church also accepted gifts of all kinds from individuals who wanted special favors or wanted to be certain of a place in heaven. The power of the Catholic Church grew with its wealth. Within time, the institution was able to influence the kings and rulers of Europe. Opposition to the Catholic Church would result in excommunication. This meant that the person who was excommunicated could not attend any church services, receive the sacraments, and, according to beliefs, would go straight to Hell when he/she died. The fear of excommunication was a strong motivator. Many proclamations were made with the understanding that excommunication was a distinct possibility if individuals disobeyed the Church’s wishes. One proclamation was the “Peace of God” or Pax Dei (poks DAY-ee). This decree was issued by local clergy and granted immunity from violence to noncombatants who could not defend themselves, beginning with the peasants and the clergy. Excommunication was the punishment for attacking or robbing a church, for robbing peasants, and for robbing, striking, or seizing a priest or any man of the clergy who was not bearing arms. Children and women were added to the early protections. The “Peace of God” prohibited nobles from invading churches, beating the defenseless, burning houses, and so on. Another proclamation, ehe “Truce of God” or Treuga Dei (trayOOH-gah DAY-ee), extended the Pax Dei by setting aside certain days of the year when violence was not allowed. Where the “Peace of God” prohibited violence against the church and the poor, the “Truce of God” focused on preventing violence between Christians, specifically between knights. An initial ban on fighting on Sundays and holy days, e.g. Christmas & All Hallows Eve, was extended to include all of Lent and even the Friday of every week. The power of the Church was also seen in its ability to exclude whole towns or even kingdoms from sacraments and religious services. “Interdicts” were frequently proclaimed, either actually or as a threat, against disobedient monarchs throughout the Middle Ages. These interdicts involved the withholding of certain sacraments and clerical offices from certain persons and even whole territories.