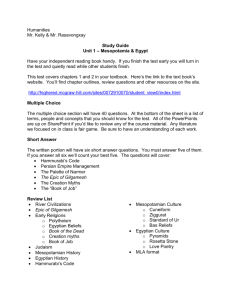

Law's Box: - UMKC School of Law

advertisement