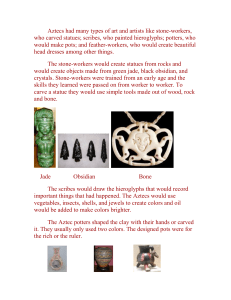

headdresses - Extras Springer

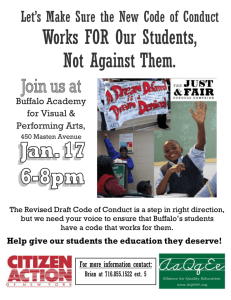

advertisement