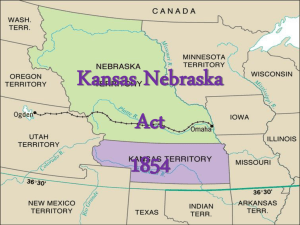

Kansas v. Hendricks

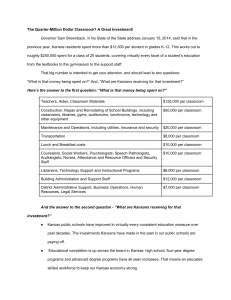

advertisement