B. Duns Scoti: Ordinatio, I, prolog., pars prima

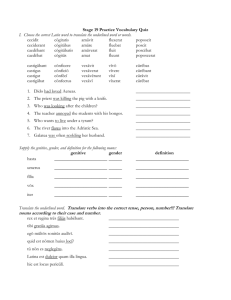

advertisement