chapter one - basics of life insurance

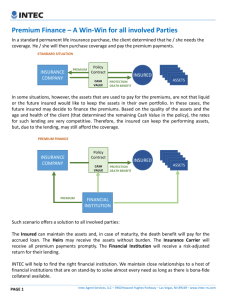

advertisement