history2

advertisement

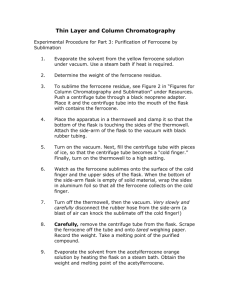

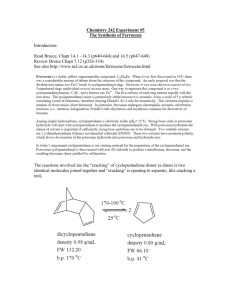

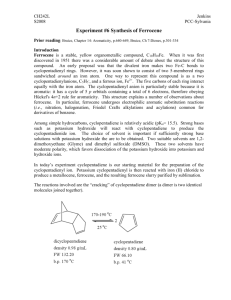

Simple chance, coupled with astute observations, has been responsible for the discovery of many new compounds. Often, in the course of what is thought to be a straight forward synthesis or investigation. Something completely unexpected happens. Perhaps a precipitate forms, a gas is evolved, a reaction mixture turns an unusual color, or a yield of expected product is very low. Some curious chemist tries to find out what “went wrong” and in that process usually makes a significant, sometimes a spectacular discovery. The discovery and characterisation of the structure of ferrocene, Fe(C5H5)2 in the early 1950's, led to an explosion of interest in d-block metal carbon bonds and brought about development and the now flourishing study of organometallic chemistry. Prior to the 1950's few d-block organometallics were synthesized and characterized. The first one, an ethylene complex of platinum(II), was prepared by W.C. Zeise in 1827. In 1890's Ludwig Mond and co-workers synthesized the first metal carbonyl, tetracarbonylnickel. However, the structures of such complexes were difficult to deduce using chemical methods, and thus it wasn't until the 1950's when NMR and single crystalX-ray diffraction could be used to solve the structures of these complexes in solution and solid state respectively. The serendipitous discovery in 1951 of ferrocene, the first recognized sandwich compound, opened an entire new era of research, and since that time numerous cyclopentadienyl derivatives of various metals and metalloids have been reported. Today such compounds have not only contributed to our theoretical knowledge of chemical bonding but also have found industrial applications ranging from antiknock additive to polymerization catalysts. The development of the chemistry of sandwich compounds of transition metals, which revolutionized organometallic chemistry and had a significant impact on the broader fields of inorganic, organic and theoretical chemistry. The rapid growth in the study of organometallic compounds by research groups around the world led to the Nobel Prize awarded in 1974 to Ernst Fisher and Geoffrey Wilkinson for their contribution to the field. In 1950, R. D. Brown of the university of Melbourne had predicted that hypothetical hydrocarbon fulvalene should be a non-benzenoid molecule. The molecule is shown below. In order to test Brown’s prediction, Pauson assigned the synthesis of this compound to his new research student Thomas J. Kealy. But in 1939 Gilman and his worker had described the synthesis of biphenyl in almost quantitative yield by treating the Grignard reagent phenylmagnesium bromide with iron, cobalt, and nickel chlorides. C6H5MgX + MX2 ------- C6H5C6 H5 + MgX2 + MX[or M] The first reported experiment for the coupling of phenyl was done with phenylmagnesium bromide and chromic chloride. The results for the Gilman experiment are shown below. Metallic halide FeCl2 CoBr2 NiBr2 RuCl3 RhCl3 PdCl2 Mole 0.01 .01 .03 .0036 .0036 .00566 Mole(C6H6MgI) .03 .03 .095 .0108 .013 .0163 % Yield 98 98 100 99 97 98 Considering the results obtained above by different chemists, Pauson attempted to synthesize dihydrofulvalene by refluxing cycopenatadienylmagnesium bromide with anhydrous iron(III) chloride in an anhydrous ether and decomposing the reaction mixture with iced ammonium chloride solution. The normal reaction leads to reduction of the ferric salt and with excess reagent results in the formation of metallic iron according to the equation shown below. Similar reaction showed biphenyl as product in the an earlier experiment in god yield. Although CoCl2 is more effectively used for such coupling reactions, Pauson chose FeCl3 because it was available in anhydrous form and because it might oxidize dihydrofulvalene directly to fulvalene. Instead he discovered the most famous and a new type of compound known as ferrocene, it was also the first sandwich compound ever discovered. The synthesis method is as follows. Procedure1. To a solution of a Grignard reagent ( from 18 gm ethyl bromide and 4 gm magnesium bromide with 11 gm. Cyclopentadiene) was added a 9.05 gm of ferric chloride dissolved in anhydrous ether. The mixture was allowed to stand at room temperature for 12 hours and then refluxed for 1 hour, cooled and decompsed with ice cold ammonium chloride solution, evaporation of the dried organic layer yielded an orange solid ( 3.5 gm). it was readily soluble in ether and benzene. The above orange solid that Pauson and Kealy received from their experiment was crystallized from methanol in large needles and had melting point 173 - 174 C. they also found molecular weight by cryoscopic determination in benzene, 186.5 ( C, 64.6 %, H, 5.4 %, Fe, 30.1 % ). They also found Iron gravimetrically as Fe2O3 after heating it with nitric acid under a reflux condenser. The other properties that the compound have were sublimation above 100C, insoluble and unattacked by water, 10 % caustic soda, concentrated hydrochloric acid. It was dissolved in dilute nitric acid and conc. Sulfuric acid with strong deep red solution with blue fluorescence. Pauson concluded from the analytical data that the compound was dicyclopentadienyl iron formed according to the equation. 2RMgBr + FeCl3 ---------- RFeR + MgBr2 + MgCl2 OR 2[C5H5MgBr] + FeCl3 ------ (C5H5)2Fe + MgBr2 + MgCl2 They also showed the structure of the compound as shown below. The research team of Samuel A. Miller and co-workers of the British Oxygen Company had already antedated Kealy and Pauson’s discovery by reacting reduced iron with cyclopentadiene vapor n a nitrogen atmosphere at 300C.(3). Their internal report was written in 1948, but they did not submit their article until 1951 and it was not published until the following year. Their structure was the same but their procedure was completely different than the Pauson and his co-workers. Another interesting thing was that, Geoffrey Wilkinson believed that workers at Union Carbide were probably the first to prepare the compound in the 1930’s while cracking cyclopentadiene through hot iron tubes. His suggestion was probably came after seeing the procedure used by Samuel anf co-workers. The second group used reduced iron in the form of the well known doubly promoted synthetic ammonia catalyst which can be made to react with cyclopentadiene in nitrogen at 300 C and at atmospheric pressure, to give a ellow crystalline compound, of composition C10H10Fe. They found that the iron was in its bivalent form, because the treatment of carbon tetrachloride soluion of the material with bromine in the same solvent gave a dark green precipitate, which dissolved in water togive a blue solution containing ferrous and bromide ions. The compound was charred by and reduces sulfuric acid and decolorises acid potassium permanganate. In the reaction the iron was proceeding only 10-15 minutes and after that the residual reduced iron was unchanged in regard to its activity as a catalyst with respect to synthesis of ammonia at 550 C. The initial rate of production of iron and the total periond of reaction before inhibation sets in both were increased by about 3 fold by the addition of molybdenum oxide to the doubly promoted catalyst. Procedure2 Ferric nitrate (3 kg) and a aluminum nitrate (300 g) were dissolved in distilled water, and treated with KOH as a 40 % solution. The ppt was separated on the centrifuge and washed with water. It was dried at 100 C for four hours and then at 600 C in the muffle furnace for 10 hours. It was washed and dried again and then converted into pellets. The pellets were charged into the 1”- diameter silica reactor tube as in the diagram and then reduced during 10 hours at 450 C in a 50 liter per hour stream of dry hydrogen. A short test was carried out with a mixture of nitrogen and hydrogen through the reactor to confirm the activity of the reduced iron as a catalyst for synthesis of ammonia. The cyclopentadiene was prepared by boiling with a little iron filling and astream nitrogen was passed through it and the issuing mixture of monomer and dimer passed up through the fractionating column surrounded by a reflux codenser. The nitrogen issuing at the top of the container was regarded as being satured with cyclopentadiene at the temperature of the coling water. After the first reaction the reactor was purged with nitrogen and then mixtures of nitrogen and air were passed through it. In order to avoid high temp on the surface of the catalyst, th eair content of the mixture was increased slowly in 5 hour steps as 5, 10, 20, 40, and 100 % of air and the temperature was gradually raised. Oxidation was considered complete when the temperatur kept quite steady wit 100 % air passing. The product in each was washed out of the receiver withether, and the ether evaporate off under reduced pressure. Some of the cyclopentadiene was recovered in the cold trap, conversion of its iron compound could only be estimated approximatey but during 15- minutes periods of activity, the conversion amounted to 40-50 %. Experiments in the presence of Molybdenum.-A solution was prepared from ferric nitrate (650 g), aluminum nitrate 29 g, ammonium molybdate (13 g) and 500 ml of water and then KOH in a small amount of water was added. The solution was stirred and conc. Ammonia was added until mixture was alkaline. Ammonia and water were evaporated to leave a pasty mess which was heated on sand bath and the resulting residue was ignited in the muffle furnace at 600 C for 6 hours. It was then formed into pellets and then passed into silica tune reactor. On the passage of nitrogen saturated with cyclopentadiene over the iron at 300C. Considerable formation of the yellow crystals were obtained but after 15 minutes the rate of production dropped rapidly. The total solid obtained in 25 minutes was 3.0 g, compared with average 1g in the absence of molybdenum. The procedure was also carried on with elevated pressure but there was no case that the product could be isolated. In the above experiments both chemists got the same product but there was only one problem, the structure they proposed was wrong. This started a debate and a new structure was proposed shortly after their paper got published. The new structure was published in April of 1952, and supported by the results, and they was proposed by R. B. Woodward, G. Wilkinson and Co-workers. They said because of the equal unsaturation of each of the carbon atoms of the cyclopentadienyl anions suggested the two such unots might form covalent bonds to ferrous ion symmetrically(4). They proposed two structures shown below as (II) and (III). Woodward and his Co-workers gave following sets of data in the support of their conclusion about their structure. Iron biscyclopentadienyl is diamagnetic. It has 25mole = -125 x 10-6 IR absorption between 3 -4 . Sharp band at 3.25, indicates only one type of C-H bonds. Ultraviolet shows maxima at 326 m ( = 50 ) and 440 m ( = 87 ). The dipole moment is effectively zero ( 0.05 D ). It has detectable vapor pressure at 0. It resists pyrolysis at 470. It readily oxidises to blue cation [ Fe( C6H5)2]+. Polarographic studies show an oxidation potential of -0.05 The perchlorate in 1N perchloric acid showed max. 253 m ( = 13,300). The cation isolated as the crystalline tetrachlorogallate and picrate. The cation isolated as the crystalline tetrachlorogallate and picrate. Analytical calculations Carbon 30.25 30.47 46.35 45.99 Gallate Found Picrate Found Hydrogen 2.54 2.77 2.92 3.27 Iron 14.02 13.97 13.48 13.43 Galium 17.52 17.52 N =10.13 N= 10.05 Chlorine 35.76 35.70 --- In July 5, 1952 a new article appeared in the journal of American chemical society in which Woodward, Rosenblum and whitting gave the name ferrocene to iron biscyclopentadienyl and also discussed more properties of this new compound. They proposed the name ferrocene because in experiments, it demonstrated the aromatic properties and also it had two rings each of five equivalent C-H groupings. The new experiments showed that it did not react with maleic anhydride and was not hydrogenated under normal conditions over reduced platinum oxide. It gave red diacetyl derivative in the presence of aluminum chloride, m.p. 130 - 131C. Derivatives and their melting points Derivative Dioxime bis--chloropropionylferrocene bisacrylolferrocene dibenzyl ester dimethyl ester m. p. ( C ). decomposes > 200 117 - 121 71 - 71.5 144 - 144.5 114 - 115 Ferrocene dicarboxylic acid pK1 3.1x10-7 pK2 2.7x10-8 pK 2.4x10-7 Benzoic acid The acidity constants are great interest and they are usually measured in ethanol or water. The very small difference between the two dissociation constants of ferrocene dicarboxylic acids indicate that the carboxyl group interact very little, and must be very far apart, while the near identity of the first constant with that benzoic acid demonstrates that the ring carbon atoms of ferrocene and necessarily the central atom as well are substantially neutral. This observation is very important in respect to the detailed electronic structure of ferrocene. Infrared spectrum H-R R = ferrocene, 3.26 CH3 C = O R CH3O C = O R CH3O O CC6H4C = O R 5.97 5.82 6.02 Other bands, 3.28 3.31 5.93 5.81 5.97 The next step in proving the structure comes from the article written by Dunitz and Orgel from Nature journal which was published in January 17, 1953. In that journal the author showed X-ray evidence for the correctness of structure ( II ), which was suggested by Woodward and co-workers. Dunitz and Orgel showed that the structure of ferrocene was monoclinic with cell dimensions as shown. a = 10.50 A c = 5.95 A b = 7.63 A = 121 space-group P2/a The measured density of 1.516 g/cc showed 2 molecules per cell, and thus required the two iron atoms to be at the cell corner and body center. The cell symmetry requires that the molecule is centro-symmetric, with the iron atom at its center. Each molecule possessed a center of symmetry occupied by the iron atom which contributes either +2Fe or zero to the structure factors according as h + k is odd or even. They showed the main features of the structure from the initial projections of the electron density on the ( 010) and (001) crystals planes. The function (xz) computed with all positive signs and was shown and it will be seen on the next page as fig1. In that figure they resolved four of the five atoms in each cyclopentadienyl and the fifth was obscured by the heavy iron peak at the origin. Similarly (xy) in which all terms with h + k = 2n were taken as positive and the functions (xy) will be shown as fig2. The plane of the cyclopentadienyl ring was normal to the projection plane and the individual atoms were not resolved but they showed the general shape of the molecule which was obvious. Fig. 1. Plot of function (xz) shown by Dunitz. Contour lines were drawn at equal arbitrary intervals except for the iron atom, where the intervals had been increased by a factor of four for the sake of clarity. Fig. 2. Plot of function (xy) shown by Dunitz and Orgel. Contour lines were drawn at equal arbitrary intervals except for the iron atom, where the intervals had been increased by a factor of four for the sake of clarity. Fig. 3. The three dimensional Fourier analysis completed by Dunitz and Orgel and an electron density map of the complete molecule obtained from their work is shown here. The above three projections considered together leave no doubt that the sandwich structure proposed was correct. They also suggested that the set of d-orbitals transforms in the group D5d = C5v , according to the following scheme : dz2 A 1g dxz , dyz E 1g dx2-y2,dxy E2g. The - orbital of the cyclopentadieny radical, according to simple molecular orbital theory, are A1, E1, and E2 in order of decreasing stability. For two cyclopentadienyl radicals oriented as in this molecule, each pair of orbital can combine to give two orbital transforming as even ( gerade) or odd ( ungerade) representations. The viberational spectra of ferrocene was obtained. IR spectra in CCl 4, CS2 and Nujol solutions were obtained in the region from 2-25 and also Raman spctras were shown. The excitation was accomplished with the Hg 5770 - 5790A doublet as well as Hg 5461A line using the appropriate filters. It was found that intensity of the Raman scattering for ferrocene was rather sharply dependent on the concentration and that for a given wavelength there existed an optimum concentration for maximum intensity. Evidence for equivalent multiple bonds resulting from delocalization of electron of the cyclopentadienyl rings is the appearance of multiple bond frequencies near 1410 cm-1. Table. The Raman and Infrared spectra of ferrocene ( cm-1). Raman Infrared 303 m 388 w 478 s 492 s 782 w 811 s 864 w 1002 s 1051 w 1108 s 1188 w 1010 w 1050 w 1105 s 1178 m 1356 w 1408 m 1411 s 1620 m 1650 m 1684 m 1720 m 1758 m 3085 m 3099 s 3085 s A polarogram of the ferricinium salt solution resulting from the electrolysis, showed a well defined cathodic wave with a half-wave potential of + 0.30 v. versus the S. C. E. agreeing, within the limits of experimental error, with the half - wave potential for the oxidation of ferrocine. The ferrocene-ferricinium ion couple is hence a thermodynamically reversible system in the alcoholic supporting electrolyte. (C5H5)2Fe = [(C5H5)2Fe]+ + e- ; Eo = -0.56v. In Nov, 1952 some other properties of ferrocene were published, in which they measured vapor pressure and vapor densities of the compound. They used two samples such that one was completely vaporized at 190C, and the other at 290 C. The vapor was found to obey the perfect gas law up to 400C. A molecular weight of 186 was calculated for the vapor, proving it to be monomeric and un-dissociated over the temperature range studied. The vapor pressures of the solid were represented by the equation. log P mm = 7.615 - ( 2470 / T ) For the liquid. log P mm = 10.27 - ( 3680 / T ) From the equations they calculated the following constants. Kcal / mole heat of sublimation of solid 16.81 heat of vaporization of liquid 11.30 heat of fusion 5.50 triple point 183 normal boiling point 249 Trouton’s constant 21.2 Fig1-Vapor pressure of ferrocene shown below. They also showed the ultraviolet absorption spectrum in hexane and it shows maxima at 325 and 440 m in agreement with the old values. The spcctra in ethanol and methanol were practically the same with that hexane, indicating little if any solvation by alcohols. In carbon tetrachloride the 440 m peak was little changed but there was very marked increase in absorption below 400 m, as compare with solutions in the other solvents. The spectra obeyed Beer’s law over a 50- fold concentration range and was unchnaged after standing several week in dark. Fig 2. shows the absorption spectra. In January, 1953 the electronic structure of ferrocene was considered by constructing the molecular orbitals from the atomic orbitals of the iron atom and the molecular orbitals of the cyclopentadienyl radicals. The structure proposed for ferrocene belonged to the symmetry group C5v. The AO’s of iron and the MO’s of the cyclopenadienyl can be divided in groups according to their symmetry with respect to z-axis of iron. Since the molecular orbitals cyclopenadienyl with one or more nodes occur in degenerate pairs, linear combinations of such molecular orbital pairs can always be constructed. The available orbitals with their symmetry classifications are listed in table (III). The orbitals of separate cyclopenadienyl by radicals were replaced linear combinations coresponding orbitals from both radicals. From these orbitals the following MO’s for ferrocene were constructed: 1 = ( s Cosa + dz Sina) Cos1 + 2-1/2 ( 1+ 1 ) Sin1 2 = pz Cos2 + 2-1/2 ( 1- 1 ) Sin2 3 = px Cos3 + 2-1/2 ( 2+ 2 ) Sin3 4 = d x+z Cos4 + 2-1/2 ( 2- 2 ) Sin4 5 = py Cos5 + 2-1/2 ( 3+ 3 ) Sin5 6 = dy+z Cos6 + 2-1/2 ( 3- 3 ) Sin6 7 = dx+y Cos7 + 2-1/2 ( 4+ 4 ) Sin7 8 = dxy Cos8 + 2-1/2 ( 5+ 5 ) Sin8 9 = s Sina - dz Cosa 10 = 2-1/2 ( 4- 4 ) 11 = 2-1/2 ( 5- 5 ) 12 = dxy Sin8 + 2-1/2 ( 5+ 5 ) Cos8. The orbitals 13 to 19 followed as negative combinations corresponding to 1 to 7. 1 to 7 are bonding orbitals, and all are doubly occupied, 9 to 11 are nonbonding, and 12 to 19 are antibonding orbitals. The value of the i may be determined by solution of the secular equations and will depend on the energies of the component orbitals and the overlap and resonance integrals between them. Since 4 and 5 are normally unoccupied high energy orbitals of cyclopntadienyl, and s and d z are noramally occupied low energy orbitals of iron, it is reasonable to assume that the two electrons which remain after orbitals 1 to 8 are filled will occupy 9. Consequently these electrons were paired and the compound was diamagnetic. If ferrocene would be paramagnetic then these electrons were to occupy the degenerate orbitals 10 and 11. The great stability of ferrocene is the result of two factors. The rare gas electron configuration of the iron atom and the existence of eight bonding molecular orbitlas. Table (iii) is shown below with their symmetry classifications. Iron s, pz, dz Cyclopentadienyl 2-1/2 ( 1 1 ) Symmetry a1 pz , dx+z 2-1/2 ( 2 2 ) b1 py , dy+z 2-1/2 ( 3 3 ) b2 dx+y , dxy 2-1/2 ( 4 4 ) ; a2 2-1/2 ( 5 5 ) The interpretation of the ultraviolet absorption spectrum of ferrocene was also discussed. The longest wavelength absorption band ( = 440 m ) can be attributed to a charge transfer transition, 9 10. This transition is forbidden by symmetry and can occur only since symmetry is distorted by vibrational motion. The second absorption band ( = 326 m, max = 50 ) must be also a forbidden transition. In this case the upper level arising from a splitting of the degenerate orbitals 10 and 11, or it may be a transition to the to lowest antibonding orbital (9 12). The intense far ultraviolet absorption (( = 225 m, = 50 ) must arise from excitation of one of the bonding electrons to a nonbonding or anti bonding molecular orbitals (12 or 8 10,11 ). Since the orbitals 8 and 10 to 12 all belong to class a2, either transition is allowed and therefore the observed high intensity is consistent with the proposed structure. The structure of ferrocene was also confirmed by electron diffraction in the 1955. The results obtained were in excellent agreement with the highly symmetrical “ sandwich” structure proposed by wilkinson. The experimental results were best satisfied by a molecular scattering intensity curve which is the average of intensity curves calculated for staggered and eclipsed configurations of the cyclopentadienyl rings. The Scalc / Sobs ratio for the best staggered, eclipsed, and average configurations are (1.0000.003, 1.0000.004, and 1.0000.001) respectively. This may be deemed to indicate that at the vapor temperature ( 400C ) the rings rotate freely about the common orthogonal axis. This result may be compared with the earlier observation of a staggered configuration in the crystal state, of a restricted rotation for ferrocene in solution (both presumably at room temperature). All the studies so far had stated that no major barrier exists against free rotation of the cyclopentadienyl rings around the orthogonal axis. According to Moffit, the electron densities of the bonding iron orbitals are axially directional but rotationally non directional. A small barrier to rotation may arise from the H-H, H-C, and C-C interactions between the cyclopentadienyl rings which are not considered in these theoretical descriptions. However, it is noteworthy that the separation of the rings ( 3.25A ) is also very similar to that in graphite ( 3.35A ). Therefore, there is little direct binding between the rings. Table for Bond length results for ferrocene. Bond Fe - C C-C C-H Length and error in A 2.030.02 1.430.03 1.090.01 The NMR spectra of ferrocene showed a single, sharp resonance peak and the variation with temperature of the width of the single resonance line has been interpreted in terms of the orientation of the cyclopentadienyl rings about their five fold symmetry axes. The resonance shows a progressive narrowing when the temperature is decreased from -48C to -158C. This has been attributed to the conversion of molecules in the eclipsed to the staggered configuration stable at low temperatures. The interaction between protons is larger in the eclipsed form than in the staggered configuration. The most striking feature of the IR spectra is its simplicity arising from the high symmetry of molecules. In addition to C-H stretching frequency at 3075 cm-1, in the region typical for aromatic C-H bonds, there are four other strong bands. Two of these, at 811and 1002 cm-1 arise from C-H bending vibration and one at 1108cm-1 is an antisymmetrical ring breathing and one at 1411cm-1 an antisymmetrical C-C stretching vibration. The IR spectra of ferrocene is shown bwlow. It has been observed that the four strong bands are retained at the same positions in all monosubstituted ferrocene derivatives, but all four strong bands disappear when buth rings are substituted. The IR spectra of ferrocene and acetylferrocene are shown. note that the carbonyl vibration is observed at 1650 cm-1. This band is much lower than the carbonyl vibration of acetylbenzene at 1686 cm-1, which reflects the difference in electron releasing ability of the phenyl and ferrocenyl groups. Two of the most detailed accounts of bonding in ferrocene have been given by Shustorovich and Dahl. Both treatments SCF-LCAO-MO method for calculating the energy levels but differ in that one uses Slater function and the other uses Hatree-Fock orbitals instead. This difference leads to some differences in the ordering of bonding and anti-boning orbitals. In both cases, however, the three bonding orbitals of the lowest energy are A 1g, A2u, E1u. These are formed from empty metal and filled ring orbitals and contain 8 electrons. The E1g level, formed by overlap of the half filled metal and ring E1g orbitals, contain 4 electrons and the remaining 6 electrons occupy the weakly bonding E2g levels and the nonbonding A1g level. The bonding between iron and the ring as described previously is now regarded as correct. Fig. Energy level diagram for ferrocene according to Dahl and Ballhausen is shown below. Fig2. Energy level diagram for ferrocene according to Shustorovich and Dyatkina is shown below. Some of the uses of ferrocene are given below. Ferrocene, or his (Cyclopentadieny) iron, is an organometallic compound. Formula: Fe (C5H6)2. It is orange-yellow flake crystals with the smell of camphor at room temperature. Melting point: 172 ~ 174 °C. Insoluble in water. Soluble in benzene, ether, gasoline, diesel and other organic solvents. It is chemically stable and does not react with acid, base and ultraviolet. It does not decompose below 400°C and is harmless to man. 2. Applications (1) Fuel additive for burning-promoting, smoke-abatement and energysaving: It can be used in various fuels, such as diesel gasoline, heavy oil and coal, Addition of 0.1% ferrocene into engine diesel leads to fuel saving by 10~14 %, increase of vehicle speed by 10%, power output by 10 ~13 % and reduction of smoke in tail gas by 30~80 %. Furthermore, addition of 0.03% in heavy oil and 0.02% in coal can also cause reduction of fuel requirement and smoke (by over 30%). (2) Additive in synthetic gasoline and synthetic LNG: Addition of 0.01 ~0.50% ferrocene and related additives in synthetic gasoline results in 80#, 85# and 90# synthetic gasoline reformulations; Addition of 0.03% in methanol can reformulate synthetic LNG with fuel value of 33472~ 38656 KJ/Kg; Addition of 0.005~0.080% in methanol- ethanol mixture can reformulate a new highly-efficient civil fuel. Addition of ferrocene in various fuel considerable benefits energy-saving, smoke abatement, pollution control, inhibiting mechanical abrasion and prolonging life of the machines. (3) Antidetonator: Ferrocene can be used as gasoline antidetonator instead of tetraethyl lead to get rid of the contamination and poisoning to man by the lead in tail gas and form high-grade lead-free gasoline. For example, addition of 0.0166~0.0332 g/L ferrocene and 0.05~0.10 g/L tert-butyl acetate can increase octane number by 4.6~6.0. (4) Polymerization and Ammonia synthesis catalysts and silicone resin and rubber curing agent: Some derivatives of ferrocene can inhibit the degradation of polyethylene by light. When used in agricultural film, they can promote its auto-degradation and self -destruction within certain period so that farming and fertiliser application are not influenced. More over, ferrocene can also be used as the protecting agent of polyethylene, polypropylene and polyester fibres to improve the thermal stability of plastics, rubber and fibres. (5) Ferrocene can be used as burning rate catalyst of rocket propellant in cosmonantic industry. (6) Ferrocene can be used as the raw material of antibiotic and bloodnourishing agents. 3. Principle of Action When ferrocene is burned together with various fuels mentioned above over 400°C, active iron ions are released which fiercely react with the oxygen in air to form active a - FezOs molecules, a - FezOs, as a burning-promoting catalyst for various fuels, can speed up the burning and make the combustion complete. More over, Addition of ferrocens in various fuel oils can increase the fraction of lower molecules, lower their fire point, complete the combustion, enhance combustion efficiency, elevate burst pressure of engines and improve dynamic performance of the vehicles. Ferrocene is also a lubricant at higher temperature and thus inhibits mechanical abrasion. Ferrocene is both a chemical catalyst and a high-temperature lubricant. With combustion takes place in engine, combination of all these actions results in fuel oil saving, smoke abatement, power increase and speed enhancement. 4. How to use The amount of ferrocene used depends on specific fuel oil. Ferrocene is added to the fuel oil and stirred until it is completely dissolved and then the oil can be filled into fuel tank and is ready for used. Alternatively, ferrocene and a certain amount of oil are mixed to form a highly-concentrated mixture, which is diluted to required concentration before use. When used in solid fuel, it can be mixed with the fuel mechanically or dissolved in some solvent ( i, g, diesel, ethanel) and sprayed onto the solid fuel, which is then thoroughly mixed and ready for use. The chief interest in the chemistry of ferrocene after its discovery lies in the substitution reactions which the cyclopentadienyl rings can undergo, among these is the Friedal-crafts reaction in which hydrogen is replaced by an acyl or alkyl group. The electrophilic substitution of ferrocene appears to proceed by the initial formation of a charge complex between the electrophile, E. and the orbital electrons of the metal. Support for this mechanism comes from the discovery that ferrocene can be protonated. The protination occurs at the metal and it is observed by the very field proton magnetic resonance. This provides clear evidence for the accessibility of electrons for bonding, the electrons concerned occupying the highest filled E2g levels. The intermediate charge transfer complex rearranges, resulting in partial transfer of charge to the ring undergoing substitution. Finally, loss of proton gives the substituted ferrocene. The mechanism for electrophilic substitution is shown below. The structure of ferrocene was proposed by Wilkinson and coworkers and then independently E. O. Fischer by X-ray diffraction studies, arrived at the antiprismatic structure. The X-ray diffraction studies of Eiland and Dunitz were also important in determining the structure of ferrocene. References Kealy and Pauson, Nature, 1951, 168, 1039. Miller, Tebboth, and Tremaine, J. Chem. Soc. 1952, 632. Woodward, Rosenblum, and Whitting, J. Amer. Chem. Soc., 1952, 74, 3458. Wilkinson, Woodward, Rosenblum, and Whitting, J. Amer. Chem. Soc., 1952, 74, 2125. 5. G. Wilkinson. J. Amer. Chem. Soc., 1952, 74, 6146, 6148 6. P. F. Eiland and R. Pepinsky, J. Amer. Chem. Soc., 1952, 74, 4971. 7. J. D. Dunitz and L. E. Orgel, , Nature, 1953, 171, 121. 8. E. O. Fischer and W. Pfab, Z. Natutrforsch, 1952,7b, 377. 9. Giman, H., and Lichtenwalter, M. J. Amer. Chem. Soc., 1939, 61, 957. 10. Brown. R. D., Nature, 1950, 165, 566. 11. Pauson, P. L., Quart. Rev. (London), 1955, 9, 391-414. 12. G. Wilkinson., J. Organomet. Chem. 1975, 100, 273-278. 13. Mulay and Attala., J. Amer. Chem. Soc., 1963, 85, 702. 14. Moffit, W., J. Amer. Chem. Soc., 1954, 76, 3386. 15. Dunitz, J. D., and Orgel, L. E., J. Chem. Phys., 1955, 23, 954. 16. Lippncott, E. R., and Nelson, R. D., J. Chem. Phys., 1953, 21, 1307. 17. F. A. Cotto and G. Wilkinson. Amer. Chem. Soc., 1952, 74, 5764. 18. J. A. Page and G. Wilkinson. Amer. Chem. Soc., 1952, 74, 7149. 19. J. L. Field and H. Field. Amer. Chem. Soc., 1953, 75, 2819. 1. 2. 3. 4.