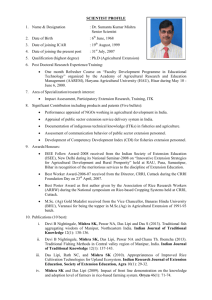

- Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade

advertisement