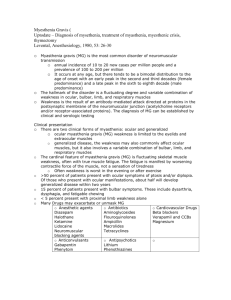

MyastheniaGravis

advertisement

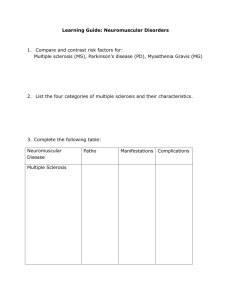

Myasthenia Gravis (MG) and Myasthenic Crisis (NEUROLOGIC EMERGENCY) Carson T. Lawall, MD Associated topics 1. Respiratory Failure in Neurologic Disease 2. Acute Inflammatory Demyelinating Polyneuropathy 3. Lambert Eaton Myasthenic Syndrome 4. Neurologic Disorders in Pregnancy Epidemiology 5-15 cases per 100,000 people. 15-20% of patients with Myasthenia Gravis have a Myasthenic Crisis in their lifetime. If one considers thymoma a neoplasm, it could be considered the most common Paraneoplastic disease. There is a bimodal distribution of disease with onset at age 20’s-30’s affecting mostly women, as well as a second group with onset age 60-70 mostly affecting men. In total 80-90% of patients will be acetylcholine receptor antibody positive, however patients who present later (in the second age group) are less likely to be antibody positive. Patients with ocular myasthenia are acetylcholine receptor antibody positive 50% of the time. There may be an association with HLA antigens B8, DRw3, and DQw2. Clinical Presentation Myasthenia Gravis (MG) Presents as fluctuating weakness of voluntary muscles, sometimes preceded by, or concomitant with, medical illness, URI, or UTI. Patients often have diplopia, ptosis, limitation of facial movement, and bulbar findings (nasal speech, difficulty swallowing) at presentation with progression to involve additional voluntary muscles of the body, although this pattern is not always seen and voluntary muscle weakness may be the first presenting sign. Dysarthria and dysphagia may also be present, especially with prolonged chewing or talking. Bulbar weakness may interfere with airway or clearing secretions. Weakness tends to worsen with repetitive use and while it may be symmetric it is often asymmetric. Myasthenic Crisis can be precipitated by infection, change in medications, and surgery. Key History: Consider Asking about, diplopia, difficulty chewing, shortness of breath, exercise tolerance, rate of deterioration, recent illness, sick exposures, surgery, travel, change in medications, herbal medications, history of fluctuating weakness/previous spells, history of intubation, difficulty walking/rising from bed/raising head, previous treatment for Myasthenia, change in diet, drug use (especially black tar heroin given risk for botulism). Myasthenic Crisis Acute respiratory failure due to worsening Myasthenia Gravis requiring admission to the intensive care unit. Presents often with generalized weakness, with or without subjective shortness of breath. Respiratory Compromise MIF >-30 is worrisome for need to intubate (MIF should be less than -30 [-40 being less than -30]) FVC <15 mL/kg or less than 1L total (some papers suggest 20mL/kg) is worrisome for need of intubation A drop of MIF or FVC 50% or greater than the first recorded value is also concerning for the need to intubate. Patients can deteriorate rapidly. Normal MIF is <-60, Normal FVC is > 60 mL/kg Respiratory failure is a frequent cause of death and may present insidiously. If a patient has bulbar weakness that precludes them from protecting their airway they may require intubation. Ocular Myasthenia Myasthenia limited to the extra-ocular movments of the eye as well as the eyelid (ptosis). Often improves with the “ice pack test” and often (50%) are Ach-R Ab negative. May not need immune suprresion in some cases (although there is limited evidence that steroid treatment may decrease the risk of developing generalized myasthenia), and can be treated with Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors. Exam ABC’s, Vitals, Mean Inspiratory Flow (MIF [or NIF in some institutions]), Forced Vital Capacity (FVC) General Medical Exam – for evidence of infection, aspiration, rash, abdominal pain/UTI. Neurologic Exam – Special attention to Cranial Nerves, papillary response (should be normal), eye movements, ptosis, weakness with sustained muscle action (fatigue with upgaze over 90 seconds, fatigue of a proximal muscle group [deltoid] and distal muscle group [finger extensors, wrist extensors), proximal muscle weakness, neck flexion/extension. Reflexes should be normal. Sensation should be preserved. Coordination deficits should be proportional to patient’s weakness. Differential Diagnosis 1. Myasthenia Gravis 2. Lambert Eaton Myasthenic Syndrome 3. Acute Inflammatory Demyelinating Polyneuropathy (AIDP/GBS) 4. Botulism 5. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) 6. Myopathy 7. Muscular Dystrophy 8. Multiple Sclerosis 9. Periodic Paralysis 10. Hypercalcemia 11. Hyponatremia 12. Hypo/Hyperkalemia 13. Hypothyroidsim (can also exacerbate MG) 14. Tick Paralysis Differential Diagnosis for Myasthenic Crisis 1. Myasthenic Crisis 2. Acetylconlinesterase overdose (AKA: Cholinergic Crisis) – Very Rare 3. Botulism 4. AIDP/GBS 5. Organic Phosphate Poisoning (pesticide poisoning) Causes/Pathophysiology Antibodies to Acetylcholine Receptors on skeletal muscle (cardiac and smooth muscle are not affected), lead to increased turnover of the Acetylcholine receptor, blockade of Acetylcholine binding of the receptor, decreased available receptor for binding, change in the neuromuscular junction leading to decreased surface area for presentation of acetylcholine receptor. Other Autoantibodies that may cause myasthenia include the Anti-MuSK (Muscle Specific Receptor Tyrosine Kinase) antibody and the Anti-Titin (a striated muscle protein) antibody, but are less common. Diagnostic testing Imaging 1. MIF and FVC – should be obtained in the emergency department as soon as possible. 2. CT or MRI chest- to evaluate for thymoma, or underlying medical illness 3. CXR – evaluate for infection or thymoma. 4. EMG/NCS – Decremental response to stimulation. Single Nerve Fiber EMG may show “jitter” which is 90% sensitive, but not specific. 5. MRI brain and orbits with and without contrast – to evaluate patients with ocular myasthenia and rule out other causes of cranial nerve or eye movement dysfunction. Laboratory Basic: CBC, ESR/CRP, CK, Serum Chemistry, iCa, Ca/Mg/Phos, U/A, Ach-R Ab (present in 80-95% of generalized MG but only 50% of Ocular Myasthenia), TSH, fT4 PPD – should be tested before immune suppression started. Antibody titers do NOT correlate to the severity of the disease. Advanced: Anti-MuSK Ab, Anti-Titin Ab, ABG*. ANA, RF, DS-DNA, cANCA/pANCA, SSA/SSB (anti Ro/La), ESR, CRP, Anti-Thyroglobulin Ab, Anti-Thyroperoxidase Ab. In some instances: Blood Cultures, Urine Cultures *Of note: ABG will be normal right until respiratory compromise so it is not a helpful marker of function, however, it may show if a patient is retaining CO2, or if they are in more dire circumstances than previously thought. Other: Tensilon test**, Ice Pack Test – can improve Ptosis if present in ~8/10 patients with MG. **Tensilon test will improve function in several neurologic diseases and is non-specific to MG. It also has some risk of fatal arrhythmia and should be done with caution. Lumbar Puncture – No role for lumbar puncture unless concerned for other causes of weakness such as AIDP. Tensilon (Edrophonium) Test 1. Place Peripheral IV, place patient on Cardiac Monitoring, have Crash Cart available. 2. Prepare Atropine 2mg in a syringe. 3. Prepare Edrophonium 10mg (1mL) in a 1mL tuberculin Syringe 4. Inject Edrophonium 2mg (0.2mL) slowly over 15 secondsand observe for side effects and clinical improvement. Improvement should occur in 30 seconds and last 5 minutes. 5. If no side effects or improvement, Inject remaining 8mg (0.8mL) of Edrophonium and monitor for symptomatic improvement. If symptomatic bradycardia, dyspnea, or syncope occurs, inject 1mg IV atropine. *There are varied regimens for the tensilon test. Treatment 1. Close monitoring and supportive Care: follow MIF/FVC every 4-6hrs until stable, mechanical ventilation if needed. Consider admission to step down unit or ICU. Avoid Incentive Spirometry as it may cause respiratory fatigue. Pay close attention to bulbar weakness and have a low threshold to make patients NPO if at risk for aspiration, or prepare to intubate if they cannot protect their airway. *Some Authors advocate that patients with severe disease or rapidly progressing disease should be treated as though they are in crisis and should be started on a rapidly acting immune therapy such as IVIG or plasmapheresis. 2. Treatment of underlying Infections/Cause – Patients with Myasthenia are often chronically immune suppressed and may be at risk for opportunistic infections, or aspiration pneumonia from poor airway protection as well as diseases in the general population. 3. Cholinesterase inhibitors*: Pyridostigmine (mestinon) – Symptomatic treatment which improves strength, however does not change the underlying disease. Dose starting at 30mg PO TID, titrate to effect 30-120mg Q3-8H, max of 1500mg/day. IV dose is 1/30th of the PO dose and can be used in patients who are an aspiration risk given bulbar weakness. Alternatively, a feeding tube can be placed for PO meds. In some cases one could consider stopping the cholinesterase inhibitor if it is not clear as the to cause of the patient’s weakness. Patients with pure Ocular Myasthenia may only require treatment with acetylcholinesterase inhibitors and not necessarily immune modulation. *overtreatment with cholinesterase inhibitors can cause weakness and possibly cholinergic crisis-however, this is very uncommon. In patients on ventilator support and/or having difficulty weaning from the vent, one may consider stopping the Cholinesterase inhibitor for a short time to see if the patient improves as patients in the ICU may have decreased clearance and overtreatment is a possibility. 4. Steroids: Steroids are the first line therapy, however they can worsen symptoms acutely through a variety of mechanisms (increased production of Acetylcholinerase, structural similarity to neuromuscular blocking agents) and must be used with caution. There are several different approaches to treatment. High dose steroids should only be initiated in the hospital as they can cause an acute decline, and one generally starts them in the setting of IVIG treatment or plasmapheresis (or must be prepared to start IVIG or plasmapheresis if the patient declines after steroids). If it occurs, steroids generally will lead to weakness 3-5 days after treatment and weakness generally lasts 3-10 days. This can occur in 50% of patients with 10% requiring mechanical ventilation. In some cases, one may prefer to start IVIG or Plasmapheresis without steroids. Steroids generally start to have an effect in approximately 2 weeks after initiation of treatment and maximal effect at 6mo to 1 year. Inpatient Regimen (High Dose) – start at Prednisone 60mg PO QDAY, then wean to lowest tolerated dose over several months to a year. Outpatient Regimen (Low Starting dose) – Start at Prednisone 25mg PO QDAY titrate to 60mg PO QDAY by increasing 5mg PO QDAY every 3-4 days and closely following clinical response then wean to lowest tolerated dose over several months to a year. It may take several trials to discover the lowest tolerated dose. One must be careful to follow the clinical course during treatment to avoid worsening which may be caused by steroids. If the patient reports worsening strength, one should consider slowing their taper or titration. Some authors suggest an alternating day regimen to reduce sided effects of steroids. Steroids are the preferred treatment in young women of childbearing age. 5. Steroid Sparing or Steroid Adjunctive therapies: (often used with steroids to achieve a lower maintenance dose, or wean off) Generally, one of the following agents is chosen: Azathioprine - Start with test dose of Azathioprine 50mg PO QDAY for 1-2 weeks and monitor for side effects, if tolerated increase with slow titration to target dose of 2-3mg/kg day. Clinical benefit is not seen for 6 months after initiation of treatment. Contraindicated in liver failure or patients with bone marrow suppression. Mycophenylate Mofetil – Start at 500mg po bid, if tolerated for 1-4 weeks, increase to 1000mg PO BID. Onset of action slightly faster than Azathioprine, 4-40 weeks (11 average). Contraindicated in patients with bone marrow suppression. Associated with a risk of leukemia. Cyclosporine – Start with Cyclosporine 2.5mg/kg PO BID (total 5mg/kg/day). One should titrate to trough level, side effects and clinical response. Generally works more quickly than Azathioprine or Mycophenylate Mofetil, as effect is seen in 1-2 months. Contraindicated in renal failure, often avoided in older patients. Other Steriod Sparing treatments: Cyclophosphamide, Tacrolimus, Rituximab. Consider review of more recent evidence if considering these therapies. 6. Surgery – Thymectomy is controversial. While no RCT has shown benefit, anecdotal evidence suggests that it is effective. Patients under age 65 (50 in some institutions) may be eligible for thymectomy. All patients with a thymoma should be considered for surgery as while it is rarely malignant it can be locally invasive. Benefit of surgery does not occur for several months or even years after the procedure. Surgery may precipitate Myasthenic Crisis, so patients should be in the best condition possible before surgery, with lowest dose possible corticosteroids to prevent problems with wound healing. Frequently patients will undergo IVIG treatment or plasmapheresis (2-5 cycles) 1 week prior to surgery to prevent worsening of disease with surgery. 7. IVIG – IVIG 1-2g/kg IV Infusion is sometimes used monthly as a bridging therapy in patients who are unable to take steroids, until another agent becomes effective such as Mycophenylate Mofetil or Azathioprine. 8. Plasmapheresis – May also be used as a bridging therapy. Myasthenic Crisis Treatment 9. Supportive Care as above 10. Steroids – Steroids do not have a clear effect in the acute management of myasthenic crisis, and may worsen symptoms. One could consider starting steroids (and some authors suggest this), however given the lack of evidence for a rapid effect and potential to exacerbate symptoms even to the point of requrining intubation, (see ref. 1) there is no clear indication for steroids. If started the beneficial effect is seen at 2-6 weeks. 11. IVIG – (many brands) – Dosed at 2g/kg total over 5 days (0.4mg/kg/day usually infused over ~6 hours but varies based on the brand and dosing instructions for the particular type of IVIG). Alternatively, 1g/kg IVIG dosed over one day was shown to be equivalent to 2g/kg IV, although there was a trend to superiority of the 2g/kg dose in a small randomized controlled trial. 12. Plasmapheresis/Plasma exchange – Dosed as one plasma volume exchange for 3-5 treatments on alternating days. There is limited RCT data, but non-randomized trials suggest significant (sometimes dramatic) improvement. In patients with respiratory failure, Plasma exchange has been shown to work faster than IVIG with more patients extubated at 2 weeks than the IVIG group (26 IVIG patients 27 Plasma exchange), but overall outcome appears to be equivalent based on this trial and Cochrane review. Adjunctive Treatments Patients on chronic steroids and immune suppression may require PCP pneumonia prophylaxis with TMP/SMZ. Chronic steroid treatment may lead to osteoporosis, gastric ulcers, infections, and diabetes mellitus and may require prophylaxis. (Calcium Supplement, Vit D, proton pump inhibitors, Glycemic Control) Patients with side effects from pyridostigmine may benefit from glycopyrrolate 1mg TID for secretions and Lomotil or Immodium for diarrhea. Prognosis Most patients will have a normal life span, however despite modern treatment, mortality for Myasthenia Gravis remains 3-8%. Formerly, Mortality for Myasthenia Gravis was over 30 percent. Medications To avoid in Myasthenia Gravis* Antibiotics Aminoglycosides – (gentamycin, tobramycin, neomycin, paromomycin, amikacin, kanamycin, streptomycin), Tetracyclines, Fluoroquinolones, Ampicillin, Azithromycin, Erythromycin, Sulfonamides, --Cephalosporins are OK. Anticonvulsants carbamazepine, gabapentin, phenytoin Cardiovascular beta-blockers (including timolol eye drops), calcium channel blockers, procainamide, quinidine, lidocaine, procaine Hormones ACTH, corticosteroids, oral contraceptives, thyroxine Neuromuscular Succinocholine, Curare Derivatives (vecuronium, rocuronium etc.) Blockers Psychiatric Phenothiazines (chlorpromazine/thorazine) Other These medications are associated with some case reports of Myasthenic Exacerbations but would not be expected to cause an exacerbation: cimetidine, citrate, chorloquine, cocaine, diazepam, lithium, quinine, trihexylphenidyl, radiocontrast, gemfibrizil, HMG-CoA inhibitors (statins) MEDICATIONS NEVER TO USE IN MYASTHENIA D-Penicillamine, Botulinum Toxin, interferon alpha *Bold Medications especially should be avoided Characteristics/Differentiation between Botulism, Cholinergic and Myasthenic Crisis Exam/History Myasthenic Crisis Cholinergic Crisis Pupils Normal/Reactive Miosis (small pupils) Possible Large pupils due to increased sympathetic drive Vision Frequent Diplopia Possible diplopia Heart Rate Bowel Symptoms Normal None Normal to Bradycardic Diarrhea, Vomiting, Increased Salivation Muscle Symptoms Weakness Cramping/Weakness Sweating Urinary Symptoms Pulmonary Symptoms Normal Normal May have shortness of breath. Diaphoresis Urinary Incontinence May Have Wheezing, Mucous Plugging, Shortness of breath Reflexes Usually Normal Usually Normal Botulism Impaired Pupillary response. Dry eyes. Blurry vision Due to loss of accommodation, and Double vision, often secondary to 6th nerve palsy. -Diarrhea, Nausea, vomiting, then constipation, ileus, due to smooth muscle paresis. Dry Mouth. Weakness, “Descending Paralysis” Normal to Anhydrosis Urinary Retention May have Shortness of breath. Normal early, then depressed or absent. Normal Mental Status Normal Possibly Confused *Not all of the above symptoms need to be present for cholinergic crisis or botulism. **Historically the Tensilon test (Edrophonium) was used to differentiate Cholinergic Crisis from Myasthenic crisis as Myasthenic Crisis should improve, and Cholinergic Crisis should worsen with edrophonium, however clinically it is unreliable, there is little utility if the patient requires ventilatory support as one would provide support until the patient improves in either scenario, and is associated with cardiac arrhythmia risk, especially in older patients. References/Recommended Reading 1. Jani-Acsadi A, Liask R. Myasthenic Crisis: Guidelines for prevention and treatment. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 2007;261:127-133 2. Discussions with Dr. Stephen Hauser and Dr. Andrew Josephson, Professors Rounds 4/2/2008 3. Mehta S. Neuromuscular Disease Causing Acute Respiratory Failure. Respiratory Care. 2006; 51 (9): 1016-1023 4. Drachman DB. Myasthenia Gravis. New England Journal of Medicine. 1994; 330:1797-1810 5. Berman B, Ambrose J, Douglas V, Ho E, Ganguly K, Kamel H, Kerchner G, Lee A, Maccotta L. UCSF Department of Neurology Resident Curriculum. 5th edition. University of Califonia San Francisco. San Francisco. 2007-2008. 6. Pascuzzi RM. Medications and Myasthenia Gravis (A Reference for Health Care Professionals) www.myasthenia.org. 2000. Updated 2007. 7. Bird SJ. Treatment of Myasthenia Gravis. UpToDate.com. https://vpn.ucsf.edu/online/content/,DanaInfo=www.utdol.com+topic.do?topicKey=muscle/45 57&selectedTitle=3~150&source=search_result. 4/15/2007. 8. Bird SJ. Chronic Immunomodulating Therapies for Myasthenia Gravis. UpToDate.com. https://vpn.ucsf.edu/online/content/,DanaInfo=www.utdol.com+topic.do?topicKey=muscle/94 65&selectedTitle=9~150&source=search_result. 1/13/2006 9. Newton E. Myasthenia Gravis. eMedicine.com. http://www.emedicine.com/emerg/TOPIC325.HTM. 3/14/2007 10. Scherer K, Bedlack RS, Simel DL. Does This Patient Have Myasthenia Gravis? JAMA. 2005;293:1906-1914 11. Schneider-Gold C, Gajdos P, Toyka KV, Hohlfeld RR. Corticosteroids for myasthenia gravis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2005, Issue 2. Art. No.: CD002828. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002828.pub2. 12. Gajdos P, Chevret S, Toyka K. Plasma exchange for myasthenia gravis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2002, Issue 4. Art. No.:CD002275. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002275. 13. Qureshi AI, Choudhry MA, Akbar MS, et al. Plasma exchange versus intravenous immunoglobulin treatment in myasthenic crisis. Neurology. 1999;52(3):629-32 14. Gajdos P, Chevret S, Toyka K. Intravenous immunoglobulin for myasthenia gravis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2008, Issue 1. Art. No.: CD002277. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD002277.pub3. 15. Geyer JD, Keating JM, Potts DC, Carney PR. Neurology for the Boards. 3rd Ed. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. Philadelphia. 2006