Headache is a common complication after a

advertisement

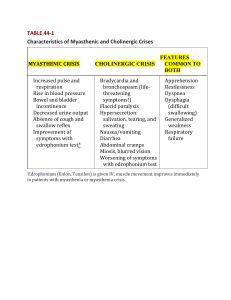

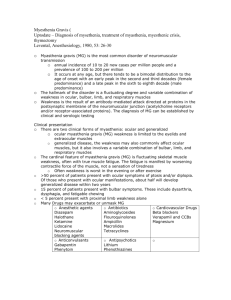

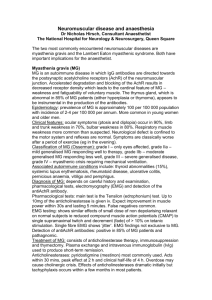

Neuro4Nurses Myasthenia Gravis Myasthenia Gravis (MG) is an autoimmune disease that affects the acetylcholine receptors (AChRs) at the post-synaptic region of the neuromuscular junctions (NMJ). Patients with MG are presented with weakness and fatigue. The weakness increases during repeated use and may improve following rest or sleep1. Epidemiology Myasthenia gravis affects individual of all ages with an annual incidence of 0.25 to 2 cases per 100,000 people. MG has a higher incidence in women than men with 3:2 ratios. Peak incidents for women are in their twenties and thirties and men are in their fifties and sixties1. Pathophysiology Skeletal muscle movement is determined by the release and uptake of neurotransmitters [acetylcholine (ACh)] between the presynaptic neurons and the postsynaptic receptors2. In MG, the anti-AChR antibodies reduce the number of the functional AChRs, widened the synaptic cleft, and damage the postsynaptic muscle membrane1. About 20% of MG patients with generalized MG do not have anti-AChR antibodies (seronegative MG). Instead some of these patients carry the muscle anti-specific kinase (MuSK) antibodies. Damage to the MuSK leads to a reduced number of AChRs and changes in AChR clustering3. Other seronegative MG patients (~5%) who do not have anti-AChR antibodies or anti-MuSK antibodies may have plasma factor that inactivates the AChRs4. Signs and Symptoms In about 65% of patients with MG, the initial symptoms or signs are diplopia, ptosis, extraocular muscle weakness, or ocular misalignment5. Ptosis can be unilateral or bilateral. Pupillary response to light and accommodation are normal2. If weakness remains restricted to the extraocular muscle, these patients are said to have ocular myasthenia gravis1. Approximately half of the patients who present with ocular myasthenia gravis, the symptoms progress to the other bulbar muscles and limb muscles, resulting in generalized MG (GMG) within 2 years4,5,6. Patient may present with a snarling expression when smiling, nasal timbre speech, dysphagia, and dysarthria. The muscle weakness in MG is painless and occurs after repetitive movement or use. The limb weakness in MG is often proximal and may be asymmetric. Deep tendon reflexes and sensory function are preserved1,4,7. Diagnostic Tests Besides clinical history, diagnosis tests of MG include neurophysiological examinations (repetitive nerve stimulation or single-fiber electromyography), assay for anti-acetylcholine-receptor antibody, and administration of short acting acetylcholine esterase inhibitors (Edorphonium)8. Computer tomography (CT scan) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have been used to evaluate changes of the thymus gland in MG patients. Edrophonium (tensilon) has a rapid onset (30 sec) and short duration (5 min). A positive result means after administration of edrophonium, the patient has improvment in weakness of extraocular muscles, impairment of speech, or the length of time that the patient can maintain the arms in forward abduction1. Ice pack test is putting an ice pack on the closed eye with ptosis. After a minute or two, patient will improve for positive result because cooling improves neuromuscular transmission and reduce the ptosis9. Treatment Options There is no cure for MG, the treatment goals of therapy are to minimize symptoms, achieve disease remission, and maintain normal function10. Anticholinesterase drugs are the first line of treatment for MG. They reduce the breakdown of acretylcholine by inhibiting the action of cholinesterase and then improving muscle strength. Pyridostigmine (MestinonTM) is the most commonly used anticholinesterase. Its effect after oral administration is 15 to 30 minutes, peak at 2 hours, and last 3 to 4 hours. Common side effects of anticholinesterase drug include abdominal cramp, diarrhea, and increase salivation11. Pathologic alterations of the thymus gland are found in 75% - 85% of MG patients. Approximately 10% of this group of patients has a thymic tumor or thymoma1,9,14. Total or extended thymectomy is the gold standard for thymomas associated with MG16. Robert et al (2001) stated that thymectomy performed on patients without thymomas significantly reduced the signs and symptoms for both ocular MG and GMG patients14. Oral corticosteroid therapy is usually used to treat mild to moderate MG. Early use of steroids in MG treatment may also decrease the risk of progression from ocular MG to generalized MG5. Immunosuppressants are used when MG symptoms are not controlled with steroid therapy or with patients who cannot tolerate the side effects of other therapies. The most commonly used immunosuppresants used for MG include mycophenolate mofetil, azathioprine, cyclosporine, cyclophosphamide, and tacrolimus. Effects of the immunosuppressants are inhibiting of T-cell development and function 12. Plasmaphoresis and Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) can be used as a short term therapy for patients whop develop a myasthenic crisis or as an adjunctive therapy in symptomatic patients. Myasthenic crisis Myasthenic crisis is defined as respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation1. It is related to inadequate dosage of anticholinesterase medication or exacerbation of myasthenic symptoms precipitated by surgery, trauma, fever, infection, or emotional stress 15. Manifestations of myasthenic crisis include acute respiratory distress, decreased urine output, increased pulse, diminished swallowing, difficulty speaking, double vision, and ptosis 16. Confirmation of myasthenic crisis is a positive Edrophonium Test. Treatment options include administration of anticholinestearse medication, plasmaphoresis, IVIG, and ventilation support and other supportive interventions. Cholinergic crisis Cholinergic crisis is resulted from overdosage of anticholinesterase drugs, which produce excessive cholinergic effects. Patients present with abdominal cramps, diarrhea, lacrimation, meiosis, excessive pulmonary secretion, bronchospasm, fasciculations, and weakness or paralysis of voluntary muscles 16. Patients with cholinergic crisis will have a negative edrophonium test. Treatments for patient with cholinergic crisis include ventilation support and holding anticholinesterase medications 16. Nursing Implications It is important to administer the anticholinestertase drugs on time (30 minutes before meals) to facilitate chewing and swallowing. Food must be eaten very slowly to prevent aspiration. Monitor patient’s nutritional intake and maintain a well balanced diet. Provide a modified diet (soft or minced) when the patient developed difficulty in eating and swallowing2,5. The respiratory status of patients with myasthenic crisis or cholinergic crisis can deteriorate rapidly. Close monitoring of patient’s respiratory status such as vital capacity, respiratory rate and pattern, SpO2, and use of respiratory accessory muscle is crucial. Support patient’s head and neck in a neutral position when they developed muscle weakness. Assist patient with the activities of daily living 2. Suctioning equipment should be available at the bedside to avoid aspiration. Encourage adequate rest and avoid fatigue, overexertion, extreme temperature, and stress2. Reference 1) Drachman, D.B. (2008). Myasthenia Gravis and other diseases of the neuromuscular junction. In A.S. Fauci, D.L. Kasper, D.L. Longo, E. Braunwald, S.L. Hauser, J.L. Jameson, & J. Loscalzo. (Eds.). Harrison’s principle of internal medicine. (17th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. 2) Hickey, J.V. (2009). The clinical practice of neurological and neurosurgical nursing. (6th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 3) Vinvent, A., & Leite, M.I. (2005). Neuromuscular junction autoimmune disease: Muscle specific kinase antibodies and treatment for myasthenia gravis. Current Opinion in Neurology, 18, 519-525. 4) Conti-Fine, B.M., Milani, M., & Kaminski, H.J. (2006). Myasthenia gravis: Pat, present, and future. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 116(11), 28432854. 5) Kupersmith, M.J., Latkany, R., & Homel, P. (2003). Development of generalized disease at 2 years in patients with ocular myasthenia gravis. Archives of Neurology, 60, 243-248. 6) Gilbert, M.E., De Sousa, E.A., & Savino, P.J. (2007). Ocular myasthenia gravis treatment: The case against prednisone therapy and thymectomy. Archives of Neurology, 64(12), 1790-1792. 7) Nations, S.P., Wolfe, G.I., Amato, A.A., Jackson, C.E., Bryan, W.W., & Barohn, R.J. (1999). Distal myasthenia gravis. Neurology, 52, 632634. 8) Schwendimann, R.N., Burton, E., & Minagar, A. (2005). Management of myasthenia gravis. American Journal of Therapeutics, 12, 262268. 9) Czaplinski, A., Steck, A.J., & Fuhr, P. (2003). Ice pack test for myasthenia gravis: A simple, noninvasive, and safe diagnostic method. Journal of Neurology, 250, 883-884. 10) Antonio-Santos, A.A., & Eggenberger, E.R. (2008). Medical treatment options for ocular myasthenia gravis. Current Opinion in Ophthalmology, 19, 468-478. 11) Armstrong, S.M., & Schumann, L. (2004). Myasthenia gravis: diagnosis and treatment. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners, 15(2), 72-78. 12) Vincent, A. (2008). Autoimmune disordwers of the neuromuscular junction. Neurology India, 56(3), 305-313. 13) Sakamaki, Y, Kido, T., & Yasukawa, M. (2008). Alternative choice of total and partial thymectomy in video-assisted resection of noninvasive thymomas. Surgical Endoscopy, 22, 1272-1277. 14) Roberts, P.F., Venuta, F., Rendina, E., De Giacomo, T., Coloni, G.F., Follette, D.M., Richman, D.P., & Benfield, J.R. (2001). Thymectomy in the treatment of ocular myasthenia gravis. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovacular Surgery, 122(3), 562-568. 15) Gunduz, A., Turedi, S., Kalkan, A., & Nuhoglu, I. (2006). Levofloxacin induced myasthenia crisis. Emergency Medicine Journal, 23(8), 662. 16) Perlo, V.P. (2004). Treatment of the critically ill patient with myasthenia. In A.H. Ropper, D.R. Gress, M.N. Diringer, D.M. Green, & S.A. Mayer. (Eds.) Neurological and neurosurgical intensive care. (4th ed.). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ©2013 Disclaimer: The author of this article neither represent nor guarantee that the practices described herein, if followed, ensure safe and effective patient care. The author further assumes no responsibility or liability in connection with any information or recommendations contained in this article. The recommendations and instructions in this article are based on the knowledge and practice in neuroscience as of the date of publication. These recommendation and instructions are subject to change based on the availability of new scientific information.