Levant_2007

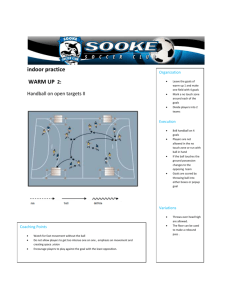

advertisement