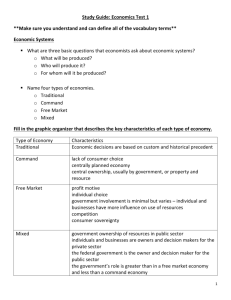

Research Proposal

advertisement