Page 1

20 of 201 DOCUMENTS

View U.S. District Court Opinion

View Original Source Image of This Document

IN RE: COMMUNITY BANK OF NORTHERN VIRGINIA MORTGAGE

LENDING PRACTICES LITIGATION; THIS DOCUMENT RELATES TO

ALL ACTIONS

MDL No. 1674, Case No. 02-cv-01201

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF

PENNSYLVANIA, PITTSBURGH DIVISION

2002 U.S. Dist. Ct. Briefs 714286; 2006 U.S. Dist. Ct. Briefs LEXIS 2628

February 15, 2006

Trial Court Brief

VIEW OTHER AVAILABLE CONTENT RELATED TO THIS DOCUMENT: U.S. District Court:

Pleading(s)

Other: Miscellaneous Expert Witness Filing(s)

COUNSEL: [**1] J. Michael Vaughan - Lead Counsel.

R. Frederick Walters.

David M. Skeens.

Garrett M. Hodes.

WALTERS BENDER STROHBEHN & VAUGHAN, P.C., 2500 City Center Square, 12th & Baltimore,

P.O. Box 26188, Kansas City, MO 64196, (816) 421-6620, (816) 421-4747 (Facsimile).

Franklin R. Nix, Esq., LAW OFFICES OF FRANKLIN NIX, 1020 Foxcroft Road, N.W., Atlanta, GA

30327-2624, (404) 261-9759, (404) 261-1458.

Scott C. Borison, Esq., LEGG LAW FIRM, LLC, 5500 Buckeystown Pike, Frederick, MD 21703, (301)

620-1016, (301) 620-1018.

Michael Cartee, Esq., John Lloyd, Esq., CARTEE & LLOYD, 2210 Eighth Street, Tuscaloosa, AL 35401,

(205) 759-1554, (205) 758-9477.

Page 2

2002 U.S. Dist. Ct. Briefs 714286, *; 2006 U.S. Dist. Ct. Briefs LEXIS 2628, **

Knox McLaney, Esq., MCLANEY & ASSOCIATES, P.C., P. O. Box 4276, Montgomery, AL 36104, (334)

265-1282, (334) 265-2319.

John W. Sharbrough, Esq., THE SHARBROUGH LAW FIRM, 156 St. Anthony Street, P.O. Box 996, Mobile AL 36601-0996, (251) 432-6620, (251) 432-5297.

Andrew Hutton, Esq., 550 West C Street, Suite 1600, San Diego, CA 92101, (619) 274-2500, (619)

839-3489.

ATTORNEYS FOR MISSOURI AND ILLINOIS OBJECTORS.

JUDGES: Hon. Gary L. Lancaster

TITLE: OBJECTORS' BRIEF ADDRESSING THE VIABILITY OF THEIR CLAIMS UNDER THE

TRUTH IN LENDING ACT AND THE HOME OWNERSHIP AND EQUITY PROTECTION ACT

TEXT: The Objectors to the now vacated class action settlement in the matter captioned "In re Community

Bank of Northern Virginia and Guaranty National Bank of Tallahassee Second Mortgage Loan Litigation,"

Case No. 03-0425 ("Kessler"), hereby submit their brief which establishes the "viability" of their claims under the Truth in Lending Act ("TILA") and the Home Ownership and Equity Protection Act ("HOEPA"). n1

While the table of contents provides a detailed view of the structure of this brief, the introduction from pages

1 through 10 provide an overall summary of how these banks pervasively [**6] violated TILA and

HOEPA; Section II running from pages 11 to 39 provides a detailed review of TILA and HOEPA liability

and damages; and Section III, set forth on pages 39 to 58 details factually these two banks' multiple and class

wide violations of TILA and HOEPA and the substantial resulting damages.

n1 The "Objectors" consist of both objectors in the Kessler matter and borrowers that opted out of that

now-vacated nationwide class action settlement but which, for ease of reference, are simply referred to

herein as "Objectors." The viability of the TILA and HOEPA claims relates not only to this specific

matter but to all of the other matters concerning the lending practices of Community Bank of Northern

Virginia and Guaranty National Bank of Tallahassee consolidated before this Court. This brief addresses only the viability of the TILA and HOEPA claims and does not address the other claims asserted by the Objectors against the Banks such as claims under the Real Estate Settlement Procedures

Act ("RESPA") or the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act ("RICO"), which claims

the Third Circuit also directed this Court to consider. In re Community Bank of Northern Virginia, 418

F.3d 277, 309-310 (3rd Cir. 2005) ("On remand, the District Court should pay particular attention to

the prevalence of colorable TILA, HOEPA and other claims that the individual class members may

have which were not asserted by class counsel in the consolidated complaint (or presumably in settlement negotiations.")) (emphasis added).

[**7]

I. INTRODUCTION

A. OVERVIEW

TILA and HOEPA are remedial consumer protection statutes. TILA applies to all consumer credit transactions, subject to limited exceptions which do not apply in this matter. 15 U.S.C. § 1603. HOEPA, which is

a part of TILA, applies only to certain high cost home mortgage loans. Nearly all the loans at issue in the

Page 3

2002 U.S. Dist. Ct. Briefs 714286, *; 2006 U.S. Dist. Ct. Briefs LEXIS 2628, **

consolidated actions (some 50,000 loans) are [*2] HOEPA loans. At its most fundamental level, TILA

requires lenders to provide accurate and timely disclosures to prospective borrowers of the true cost of a

loan. "The Truth in Lending Act was necessary exactly because borrowers could not force creditors to provide voluntarily a system of credit within which consumers could function intelligently." Parker v. De Kalb

Chrysler Plymouth, 673 F.2d 1178, 1181 (5th Cir. 1982)(citing H.R. 1040, 90th Cong., 2d Sess. (1968), reprinted in 1968 U.S.C.C.A.N. 1962, 1965-70).

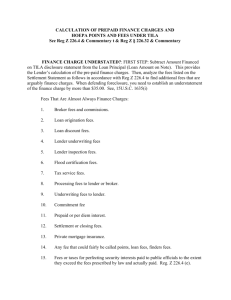

This cost is described under the commonly recognized statutory terms "Amount Financed", "Finance

Charge" and the "Annual Percentage Rate ("APR")". Community Bank of Northern Virginia ("CBNV") and

Guaranty National Bank of Tallahassee [**8] ("GNBT") (collectively the "Banks") were predatory and

abusive second mortgage loan lenders that universally violated TILA and HOEPA by misstating these terms.

Importantly, for the purpose of HOEPA, the Banks misrepresented the cost of credit by materially understating the APR on nearly every loan they made.

The APR is calculated through a mathematical formula that is derived from the Amount Financed (funds

actually available to the borrower) and Finance Charge (interest, fees and costs - what the money will cost

the borrower over the life of the loan). These two numbers are mutually exclusive; that is, a settlement

charge is allocated to either one or the other but not to both. The higher the finance charges, the higher the

APR. Generally, all fees and costs charged in connection with making the loan are, logically, part of the finance charge. With respect to real estate loans, however, certain charges may be excluded from the finance

charge such as fees related to specified title work, such as fees for the preparation of abstracts or title, and for

[*3] performing title examinations, but only if those fees are bona fide and reasonable. 12 C.F.R. §

226.4(c)(7); see also [**9] Saunders Affidavit at PP 40-42 (Exhibit 1).

Not content with the huge origination fees and other fees and interest exacted, the Banks engaged in

"loan padding" that violated TILA and HOEPA by excluding from the finance charge, as their standard practice, fees for title examinations (HUD-1 Line 1103) that were neither bona fide nor reasonable because no

title examinations were provided. See Dodson Affidavit at PP 9(B); 9(D) (Exhibit 2); Coghlan Affidavit at P

7 (Exhibit 3). Additionally, the title abstract charge (HUD-1 Line 1102) was a charge to obtain a rudimentary property report which is far from a true title abstract. Dodson Affidavit at PP 9(A); 9(C); Coghlan Affidavit at P 6. This charge was then illegally marked up and passed on to the borrower. Such a mark up is not

reasonable (and is in fact a separate violation of, among other things, RESPA). Santiago v. GMAC Mortgage

Group, Inc., 417 F.3d 384, 389 (3rd Cir. 2005). Thus, at a minimum, the amount of the mark up was improperly excluded from the finance charge. The result from the failure to include the entire title exam fee and

the mark up portion of the abstract fee in the finance charge [**10] is that the APR was materially understated in violation of TILA and HOEPA as to the loans of the Objectors and other borrowers within the consolidated actions. Saunders Affidavit at PP 43-45; Haynes Affidavit and Accompanying Spreadsheets (Exhibit 4 and 4D-F). n2

n2 Exhibit 4 and its attached Exhibits 4D, 4E, 4F and 4G are the spreadsheets and accompanying affidavit prepared for Objectors by Hasbrouck Haynes, CPA and it reflects an analysis of some 436

loans from Missouri, Illinois, Maryland, Georgia, California and Florida. Objectors had suggested to

counsel for RFC that it produce a randomly selected sampling of loan files for this viability exercise.

RFC refused the request but it did produce the loan files for Objectors (the Missouri, Illinois and Maryland files, as well as a few files for borrowers in California and Florida). Objectors additionally had

access to partial loan files for certain Georgia borrowers that were provided by those borrowers. The

Spreadsheet contains calculations to confirm that the loans are in fact HOEPA loans (all but 11 out of

436 are HOEPA loans), calculations that reveal a materially misstated APR calculation on 431 of the

436 loans and calculations to show approximate TILA and HOEPA damages for the borrowers. Additionally, based on the number of loans analyzed, which were roughly one-half CBNV loans and

Page 4

2002 U.S. Dist. Ct. Briefs 714286, *; 2006 U.S. Dist. Ct. Briefs LEXIS 2628, **

one-half GNBT, Objectors were able to make a number of projections about the 44,535 loans that are

held by RFC and were at issue in this lawsuit. Thus, Objectors will cite to these loan spreadsheets and

Mr. Haynes' Affidavit throughout this brief. Finally, while the discussion herein focuses on the 44,535

loans held by RFC that were part of the vacated settlement, certainly the findings demonstrated including the overall viability of the TILA and HOEPA claims translates to the other cases consolidated

before this Court which are estimated to concern some 5,000 additional loans.

[**11]

[*4] In addition to the disclosures mandated by TILA, HOEPA requires the Lender to warn prospective borrowers about the high cost of their loans through an advance notice - the "HOEPA Notice" - of the

loan's monthly payment amount and its certain cost information including a specific and separate disclosure

of the APR at least three (3) business days prior to closing. 15 U.S.C. §§ 1639(a), (b)(1). The HOEPA Notice gives the consumer the opportunity to reject the loan offer before being rushed to sign numerous papers

at a closing. The Banks committed an additional disclosure violation of HOEPA by failing to ensure the borrowers' actual receipt of this HOEPA disclosure at least three (3) business days prior to closing. The written

policy of the Banks was not crafted to ensure compliance with this requirement as their Operations Manuals

(which have identical language for both Banks) requires only that these advance HOEPA disclosures be only

mailed 3 business days prior to closing. Plainly, if not mailed until three days before closing, the HOEPA

Notices could not have been received by the borrower, as the law requires, three business days in advance

[**12] of the closing. Other evidence of this 3 business day HOEPA Notice violation are loan file documents that show the borrower's acknowledgement signature on the disclosure (that was to come at least 3

business days before closing) bearing the same date as the closing.

Finally, Objectors have noted that as to many loans, there also exists yet another HOEPA violation in

that despite clear a clear statutory prohibition under HOEPA for prepayment penalties except in some very

particular circumstances, see 15 U.S.C. § 1639(c); 12 C.F.R. § 226.32(d)(6)-(7), the Banks often violated this

prohibition.

[*5] HOEPA's place in this discussion is extremely relevant in at least one other way in that HOEPA's

assignee liability provisions make the ultimate purchasers of these loans liable for any and all claims the

borrowers might have against the originating lenders. 15 U.S.C. § 1641(d). Thus, assignees like GMAC-RFC

are strictly liable to the borrowers for all damages available to them under TILA and HOEPA, and under any

other statutory or common law claim like those claims asserted under RESPA or RICO.

The use of the terms "strictly [**13] liable" in the preceding sentence was purposeful. As with all remedial consumer protection statutes designed to address the inherently unequal bargaining position between

the consumer and lender, any violation of TILA and HOEPA makes the wrongdoer (or assignee) strictly liable for the statutorily mandated TILA and HOEPA damages. In re Community Bank, 418 F.3d 277, 305 (3rd

Cir. 2005) ("strict liability is imposed on the lenders and on their assignees if the APR is materially misstated

in the TILA disclosure forms").

The resulting "strict liability" damages for the noted violations are substantial. The misstatement of the

APR under TILA allows each aggrieved borrower to recover their actual damages and a statutory penalty

under 12 U.S.C. 1640(a)(1)-(2). Because this same improper APR disclosure violates HOEPA (§ 1639(a)(2);

12 C.F.R. § 226.32(c)), each borrower is entitled to the additional HOEPA damage of a return of "the sum of

all finance charges and fees" paid by them on the loan. 15 U.S.C. § 1640(a)(4). Additional violations of

HOEPA like the failure to provide the HOEPA Notice 3 business days in advance [**14] of the closing or

the violation of the prepayment prohibitions allow a borrower an additional multiples of HOEPA's enhanced

damages (again, the "sum of all finance charges and fees"). Further, these TILA and HOEPA violations give

the borrower a right of recession under 15 U.S.C. § 1635.

Page 5

2002 U.S. Dist. Ct. Briefs 714286, *; 2006 U.S. Dist. Ct. Briefs LEXIS 2628, **

[*6] As demonstrated in detail in this brief, these are viable claims that can be established on a class

wide basis. The individual and collective class damages that arise as a matter of strict liability from these

plain and provable violations is staggering as the following quick example and discussion illustrates.

Loan of Illinois Objector Sonia Gestes

Ms. Gestes took out a $ 31,300 second mortgage loan from GNBT on November 21, 2001 at 11.99% interest. Her APR was materially misstated and pursuant to the standard practice of GNBT she did not timely

receive her HOEPA APR notice and their loan contained a prohibited prepayment penalty. As explained in

detail below, her TILA/HOEPA damages are as follows:

TILA Actual Damages

Statutory Damages

HOEPA Damages

($ 20,038.33 x 3 total violations)

Monetary Value of Rescission Damage

Subtotal

Tender Obligation

Total Recovery from Defendants

$ 475.00

$ 23.00

$ 60,114.99

$ 20,038.33

$ 80,651.32

- $ 27,257.83

$ 53,393.49 n3

[**15]

n3 This number does not include attorneys' fees or costs which are also a measure of damages each

aggrieved borrower is entitled to under TILA and HOEPA. 15 U.S.C. § 1640(a)(3).

The spread sheet of some 436 loans compiled by Objectors' accounting expert shows that the total average damages for the 431 loans with violations is $ 52,565.43. Extrapolating that percentage of loans with

violations over the entire class yields (98.9% * 44,535) a total of 44,045 loans with violations. That number

of loans multiplied by the average damages provides a potential class wide recovery of a staggering $

2,315,250,409.00. Exhibit 4, at P 15. Class Counsel, however, sought to settle and forever release these

claims were being released by class counsel for between $ 250 and $ 925 under the vacated settlement.

[*7] The Brief and accompanying spreadsheet, affidavits and other evidence, which are the only evidence ever presented to the Court, readily demonstrate the viability of the Objectors' [**16] claims. In addition to the cited statutory and precedential authority, the viability is established by the Objectors' own loan

documents, the Defendants' business records, the testimony of insiders to the lending scheme, and expert testimony. The expert testimony comes in the form of affidavits submitted by HOEPA and TILA (and overall

consumer rights) expert, Margot Saunders, Esq., of Counsel to the National Consumer Law Center, whose

affidavit appears at Exhibit 1 and by title experts William H. Dodson, II Esq., and John T. Coghlan, Esq.,

whose affidavits appear, respectively, at Exhibit 2 and Exhibit 3, as well as the summary chart prepared by

Hasbrouck Haynes, Jr. C.P.A. and his accompanying affidavit, which appear at Exhibit 4.

B. RELEVANT PROCEDURAL HISTORY

The illegal lending practices of these Banks, as orchestrated behind the scenes by the unlicensed Shumway-Bapst mortgage operation resulted in a number of class action and individual lawsuits being filed

against the Banks around the Nation. Most if not all of these suits involved the assignees that had purchased

these loans from the Banks. Most notable among the assignees is GMAC-RFC Residential [**17] Funding

Corporation ("RFC") because it bought more than 44,000 of the estimated 50,000 second mortgage loans

ostensibly originated by the Banks.

In early 2003, RFC and counsel for several of the pending class actions attempted to settle their liability

for some 44,535 second mortgage loans originated by the Banks and purchased by RFC through a consolidated class action settlement in Case No. 03-0425 that was presented to this Court. The "Objectors," mem-

Page 6

2002 U.S. Dist. Ct. Briefs 714286, *; 2006 U.S. Dist. Ct. Briefs LEXIS 2628, **

bers of that settlement class, took issue with the terms of the settlement and either objected or opted out of

the settlement class. The objections [*8] were presented to this Court in what is now a well-documented

series of hearings and rulings, the ultimate result of which was the Court's rejection of the Objectors' arguments and request for intervention and the Court's approval of the class action settlement. Prime among the

Objectors' complaints was that the class action settlement released for little to no consideration valuable

claims and defenses to foreclosure under TILA and HOEPA.

Following the approval of the Settlement, the Objectors filed a number of appeals to the Third Circuit

contending, among other things, that [**18] the settlement class was never properly certified due to this

Court's failure to address the viability of the TILA and HOEPA claims and that the settlement was unfair,

inadequate and unreasonable due to the release of the TILA and HOEPA claims for no consideration.

While that appeal was pending, a number of the Opt-Outs from the nationwide settlement as well as borrowers aggrieved by the predatory lending scheme but who were not part of the class action settlement (because RFC had not purchased their loans) filed an action captioned as Hobson v. Irwin Union Bank and Trust

Company, et al., in the United States District Court for the Northern District of Alabama. The Hobson action

was then transferred to this Court as part of a multidistrict proceeding, MDL No. 1674, along with two lawsuits filed by individual borrowers in Maryland, along with the re-opened Davis action, now apparently

called Kossler. The Davis/Kossler suit is a putative class action filed in this Court that, like Hobson, included

borrowers that were not within the settlement class because their loans had not been purchased by RFC.

In August, 2005, the Third Circuit reversed this Court's approval [**19] of the settlement and remanded

Case No. 03-0425 back to this Court for further proceedings. In doing so, the Third Circuit questioned at

length the (in)adequacy of representation by Kessler class counsel in light [*9] of their failure to prosecute

or consider in the settlement amount the value of the class members' TILA and HOEPA claims. In remanding

the matter to the District Court, the Third Circuit, among other things, directed that the District Court address

conduct the instant "viability analysis" of the borrowers' TILA and HOEPA claims.

C. STANDARD OF REVIEW

Following the instruction and terminology of the Third Circuit, the Court has solicited briefing to examine the "viability" of the Objectors' TILA and HOEPA claims. What legal standard equates to the term "viable" was not articulated by the Third Circuit. Black's Law Dictionary states that something is viable if it is

"[c]apable of independent existence or standing - "a viable lawsuit." Black's Law Dictionary (8th ed. 2004).

According to Webster's Dictionary something is viable if it has "a reasonable chance of succeeding." See

Merriam-Webster's Online Dictionary (www.m-w.com/dictionary/viable). [**20]

In terms of a legal standard, Objectors submit that the appropriate standard of review to determine "viability" of a claim is the motion to dismiss under Fed.R.Civ.P. 12(b)(6) which this Court recently articulated:

When the court considers a Rule 12(b)(6) motion to dismiss, the issue is not whether plaintiff

will prevail in the end or whether recovery appears to be unlikely or even remote. The issue is

limited to whether, when viewed in the light most favorable to plaintiff, and with all

well-pleaded factual allegations taken as true, the complaint states any valid claim for relief.

See ALA, Inc. v. CCAIR, Inc., 29 F.3d 855, 859 (3rd Cir.1994). In this regard, the court will not

dismiss a claim merely because plaintiff's factual allegations do not support the particular legal

theory he advances. Rather, the court is under a duty to examine independently the complaint to

determine if the factual allegations set forth could provide relief under any viable legal theory.

5A Charles Alan Wright & Arthur R. Miller, Federal Practice & Procedure § 1357 n. 40 (2d

ed.1990). See also Conley v. Gibson, 355 U.S. 41, 45-46, 78 S. Ct. 99, 2 L.Ed.2d 80 (1957).

[**21]

Page 7

2002 U.S. Dist. Ct. Briefs 714286, *; 2006 U.S. Dist. Ct. Briefs LEXIS 2628, **

AMG Industries Corp. v. Lyon, 2005 WL 3070922, at *2 (W.D. Pa. Nov. 16, 2005)(Lancaster, J.) (emphasis

added); see also Vallies v. Sky Bank, 432 F.3d 493, 494 (3rd Cir. 2006)("A motion [*10] to dismiss pursuant to Federal Rule 12(b)(6) should be granted only if, 'accepting as true the facts alleged and all reasonable inferences that can be drawn therefrom' there is no reasonable reading upon which the plaintiff may be

entitled to relief.").

Significant to this discussion is the additional recognition that TILA is a remedial statute that is to be

"construed liberally in favor of the consumer." Household Credit Services, Inc. v. Pfennig, 541 U.S. 232, 235

(2004); Rossman v. Fleet Bank (R.I.) N.A., 280 F.3d 384, 390 (3rd Cir. 2002); see also Bragg v. Bill Heard

Chevrolet, Inc.; 374 F.3d 1060, 1065 (11th Cir. 2004)(courts are to "evaluate TILA transactions from the

consumer's viewpoint"); Lifanda v. Elmhurst Dodge, Inc., 237 F.3d 803, 806 (7th Cir. 2001)(cautioning the

courts not to deem an ordinary consumer to have the business and legal knowledge of "a Federal Reserve

Board [**22] member, federal judge, or English professor").

As established herein, Objectors more than meet a Rule 12(b)(6) standard. The Objectors' outline of the

legal basis of their claims under TILA and HOEPA demonstrates that if their factual allegations are taken as

true, then viable claims have been stated. Beyond this, Objectors provide factual and expert testimony support for their allegations. The result is that Objectors have plainly demonstrated that the TILA and HOEPA

claims present a very viable legal theory upon which relief to tens of thousands of borrowers could and

should be provided.

[*11] II. TILA AND HOEPA: AN OVERVIEW

A. STATUTORY PURPOSES AND SCHEMES

1. The Truth in Lending Act

a. The Purpose of TILA: "The Informed Use of Credit"

The Truth in Lending Act, first enacted in 1968, is a consumer protection statute. The underlying purpose of TILA is to promote the "informed use of credit" by requiring all creditors to tell consumers in terms

and with forms universal to all types of consumer lending what the true cost of the credit is to the borrower.

The Congress finds that economic stabilization would be enhanced and the competition [**23]

among the various financial institutions and other firms engaged in the extension of consumer

credit would be strengthened by the informed use of credit. The informed use of credit results

from an awareness of the cost thereof by consumers. It is the purpose of this subchapter to assure a meaningful disclosure of credit terms so that the consumer will be able to compare more

readily the various credit terms available to him and avoid the uninformed use of credit, and to

protect the consumer against inaccurate and unfair credit billing and credit card practices.

15 U.S.C. § 1601(a); see also 12 C.F.R. § 226.1(b)("The purpose of this regulation is to promote the informed use of credit by requiring disclosures about its terms and cost. The regulation also gives consumers

the right to cancel certain credit transactions that involve a lien on the consumer's principal dwelling...."); see

also Thomka v. A.Z. Chevrolet, Inc., 619 F.2d 246, 248 (3rd Cir. 1980) ("The Truth-in-Lending Act was

passed primarily to aid the unsophisticated consumer so that he would not be easily misled as to the total

costs of financing"). n4 Making lenders tell [**24] borrowers in universal terminology the true cost of the

loan enables the consumers' ability to understand that cost and comparison shop. Parker, 673 F.2d at 1181;

Mason v. Gen. Fin. Corp., 542 F.2d 1226 (4th Cir. 1976); Curtis v. Secor Bank, 896 F. Supp. 1115, 1118

Page 8

2002 U.S. Dist. Ct. Briefs 714286, *; 2006 U.S. Dist. Ct. Briefs LEXIS 2628, **

(M.D. [*12] Ala. 1995)("The TILA regulates primarily by providing uniform disclosure requirements and

standard definitions of credit terms."); Saunders Affidavit, at PP 31-35.

n4 TILA does not, however, govern or limit the charges that may be imposed in a credit transaction.

See 12 C.F.R. § 226.1(b). Such regulation is left to other federal law, such as RESPA, 12 U.S.C. §§

2601, et seq., and state law.

b. The Organization of TILA

TILA is found at Title 15, Chapter 41, Subchapter I of the United States Code, or, beginning at 15 U.S.C.

§ 1601. Part A of TILA (§§ 1601-1615) sets forth General Provisions of TILA and defines terms, including

[**25] the Finance Charge. Part B of TILA (§§ 1631-1649) sets forth rules for Credit Transactions, and the

rules sometimes differ for closed-end credit transactions, open-ended transactions and variable rate transactions. Part C of TILA (§§ 1661-1665b) deals with Credit Advertising. Part D of TILA (§§ 1666-1666j) deals

with Credit Billing and Part E (§§ 1667-1667f) deals with Consumer Leases. The second mortgage loans at

issue are closed end credit transactions governed by Parts A and B.

TILA also incorporates regulations issued by the Federal Reserve Board as part of its requirements, such

that "any reference to any requirement imposed under this subchapter or any provision thereof includes reference to the regulations of the Board." See 15 U.S.C. §§ 1602(y); see also 15 U.S.C. § 1604(a)(delegation

of authority to Federal Reserve Board to enact regulations to effectuate TILA's disclosure purposes); Household Credit Services, Inc. v. Pfenning, 541 U.S. 234, 235-36 (2004)("Congress delegated expansive authority

to the Federal Reserve Board (Board) to enact appropriate regulations to advance this purpose. § 1604(a).

[**26] "); Jumbo v. Nester Motors, Inc., 428 F. Supp. 1085, 1086 (D. Az. 1974)("any reference to the requirements imposed by the Act is also a reference to the relevant regulations"); see also Saunders Affidavit at

P 15. Those regulations are found at 12 C.F.R. Part 226, and are generally and commonly referred to as

"Regulation Z." Thus, any discussion of TILA necessarily requires an analysis of both the federal statutes

and the federal regulations.

[*13] The class loans at issue are generally governed by the following parts of Regulation Z. Subpart

A of 12 C.F.R. Part 226 (12 C.F.R. §§ 226.1-.4) sets forth General Regulations for TILA, and defines terms,

including the Finance Charge at § 226.4. Subpart C (§§ 226.17-.24) sets forth regulations for Closed-End

Credit and includes a regulation on the determination of the Annual Percentage Rate. Subpart E (§§

226.31-.35) sets forth special regulations for certain types of mortgages, such as HOEPA mortgages, which

are defined at 15 U.S.C. § 1602(aa) and at 12 C.F.R. § 226.32 and are sometimes referred to as "Section 32"

mortgages as a result of Regulation Z's definition. Finally, following [**27] Part 226 are a number of Appendixes that deal with unique issues under Regulation Z, including the determination of the Annual Percentage Rate in Closed-End Transactions at Appendix J.

In addition, "Congress has specifically designated the [Federal Reserve Board] and staff as the primary

source for interpretation and application of truth-in-lending law." Household Credit Services, Inc., 541 U.S.

at 238. These interpretations of TILA are found in Supplement I to Part 226 (following the Appendixes) and

are commonly referred to as the "Official Staff Interpretations" or "Official Staff Commentary" to Regulation

Z.

2. The Home Ownership and Equity Protection Act

In 1994, Congress recognized the need to take further action to curb predatory lending. Congress found

that several high-rate lenders were using non-purchase money mortgages to take advantage of unsophisticated and low income homeowners in a "predatory" fashion. See S. Rep. 103-169, 1994 U.S.C.C.A.N. 1881,

1907. A fundamental problem of these high cost loans secured by any remaining equity in a borrowers' home

Page 9

2002 U.S. Dist. Ct. Briefs 714286, *; 2006 U.S. Dist. Ct. Briefs LEXIS 2628, **

is that it exposed borrowers to a heightened risk of foreclosure and the bleeding or stripping [**28] of the

equity out of what, in most cases, is an individuals biggest financial investment. See generally Saunders affidavit at PP 8-14.

[*14] In response, Congress overwhelmingly passed the Home Ownership and Equity Protection Act,

codified at 15 U.S.C. 1639 ("HOEPA") to the Truth in Lending Act, 15 U.S.C. Sec. 1601, et seq. It provides

extraordinary and additional protections and rights to borrowers obtaining a special type of loan - a "high

cost/high interest" loan defined at 15 U.S.C. § 1602(aa) and at 12 C.F.R. 226.32. A "HOEPA loan" is defined

as a mortgage loan "secured by the consumer's principal dwelling," other than a loan made to finance the

dwelling's original construction or acquisition, in which (1) the loan's annual percentage rate of interest exceeds ten percent of "the yield on Treasury securities having comparable periods of maturity on the fifteenth

day of the month immediately preceding the month in which the application for the extension of credit is received by the creditor;" or (2) the "total points and fees" payable by the consumer at or before the closing

exceeds the greater of eight [**29] percent of the "total loan amount" or $ 400. See 15 U.S.C. §

1602(aa)(1)(A) & (B); 12 C.F.R. § 226.32.

In establishing the triggers to determine whether a loan was predatory, and therefore subject to HOEPA

and its special disclosure requirements, enhanced damages and assignee liability, Congress made specific

findings. It determined that loans made by any lender who charged over 8% in fees and points would be subject to HOEPA. In setting the 8% bright line test Congress found that the 8% level for points and fees was

well above the industry average. The 8% trigger was to "prevent unscrupulous creditors from using grossly

inflated fees and charges to take advantage of unwitting consumers." S. Rep. 103-169, 1994 U.S.S.C.A.N.

1881, 1908.

In this case, nearly all of the loans at issue in this lawsuit are HOEPA loans. This is established not only

by the Defendants' own documents, like the HOEPA notice to assignees appearing in the loan files, but also

by the independent review of Objectors' Experts. All of the [*15] loan files reviewed by Ms. Saunders are

HOEPA loans. Saunders Affidavit at P 20. Moreover, of the 436 loans that make up the Objectors' Spreadsheet, [**30] Mr. Haynes confirmed that all but 11 or some 97.5% are HOEPA loans. See Exhibit 4, at P

8.

a. Additional HOEPA Disclosure Requirements

HOEPA requires additional disclosures that supplement and are "in addition to" the TILA disclosure requirements. 15 U.S.C. § 1639(a); 12 C.F.R. § 226.31(a). Specifically, creditors making HOEPA loans are

required to make a "Miranda-like" warning of the consequences of entering into the loan to HOEPA borrowers at least three business days before the consummation, or closing, of the loan. 15 U.S.C. § 1639; 12 C.F.R.

§§ 226.31(c); 226.32(c). This disclosure must also include the APR on the loan and identify the regular

monthly loan payments to be made on the loan. In addition, these disclosures must be made in a clear and

conspicuous type size and each borrower must receive a copy of the HOEPA Disclosure in a form that they

can keep. 15 U.S.C. § 1639(a); 12 C.F.R. §§ 226.31(b)(1); 226.32(c) & (e).

Importantly, because HOEPA has a specific requirement for the disclosure of the APR, when a lender

inaccurately calculates the Finance Charge or the Amount Financed, [**31] the APR will also be inaccurately calculated, thereby violating both TILA and HOEPA if the tolerances for error are exceeded as

demonstrated in Objectors' spreadsheet. 15 U.S.C. § 1606(a); 12 C.F.R. §§ 226.31-.32; see also Appendix J

to 12 C.F.R. Part 226 ("Annual Percentage Rate Computations for Closed-End Credit Transactions"). Arguably then, the advanced notice and APR disclosure are the most important features of the TILA and HOEPA

disclosure.

Tb. HOEPA Prohibitions on Certain Abusive Loan Terms and Creditor Practices

A creditor making HOEPA loans is prohibited from including certain terms in the loans. 15 U.S.C. §

1639(c)-(e). These prohibited terms include prepayment penalties (unless an [*16] exception applies); in-

Page 10

2002 U.S. Dist. Ct. Briefs 714286, *; 2006 U.S. Dist. Ct. Briefs LEXIS 2628, **

terest rate increases on default, balloon payments, negative amortization, prepaid loan payments, and

due-on-demand or acceleration clauses. Id.; see also Saunders Affidavit at P 18. As explained below,

HOEPA's restrictions on prepayment penalties were also violated as to a significant number of the borrowers.

A HOEPA creditor is also prohibited from engaging in certain practices such as extending credit [**32]

to HOEPA borrowers without regard to their ability to repay the loan, engaging in "loan flipping" (refinancings by the same lender within a one-year period) and paying the proceeds of HOEPA loans to home

improvement contractors. See 12 C.F.R. § 226.34(a)(1), (3)-(4).

c. Assignee Liability

Purchasers and assignees of HOEPA loans are liable for all claims and defenses that the borrowers could

assert against their creditor, including, but not limited to, all TILA and HOEPA violations. 15 U.S.C. §

1641(d) ("Any person who purchases or is otherwise assigned a mortgage referred to in section 1602(aa) of

this title shall be subject to all claims and defenses with respect to that mortgage that the consumer could assert against the creditor of the mortgage..."). The reason for imposing assignee liability is to directly address

the determination of Congress that borrowers obtaining HOEPA loans were most susceptible or vulnerable to

predatory lending practices. See McIntosh v. Irwin Union Bank and Trust, Co., 215 F.R.D. 26, 29 (D. Mass.

2003)("HOEPA, an amendment to TILA, was enacted 'to ensure that consumers understand the terms of such

loans [**33] and are protected from high pressure sales tactics ... [it] prohibits High Cost Mortgages from

including certain terms such as prepayment penalties and balloon payments that have proven particularly

problematic.'"); Saunders Affidavit at P 18. By making assignees liable for the sins of the originating lender,

"Congress intended to force the [*17] "High Cost Mortgage" market to police itself." Bryant v. Mortgage

Capital Resource Corporation, 197 F. Supp.2d 1357, 1364 (N.D. Ga. 2002); see also Saunders Affidavit at P

18.

Pursuant to the imposition of assignee liability, the originating lender is required to provide a notice to

the assignee that the loan they are acquiring is a HOEPA loan. 15 U.S.C. § 1641(d)(4); 12 C.F.R. §

226.34(a)(2). There is no dispute that the assignees in this matter and the other consolidated actions, RFC,

Irwin Union and others, received such notices and knew they were buying HOEPA loans.

It is anticipated that RFC and other assignee defendants will argue that all § 1641(d) does is get rid of the

holder in due course defense such that it is not available to them should a borrower try to use any illegal

[**34] acts by the lender bank to thwart a foreclosure action by the assignee. That is, that § 1641(d) does

not allow the assertion against the assignees of a borrowers' affirmative claims. Any such argument must fail

as it is contrary to the plain language of § 1641(d).

The statutory language is clear. The statute "eliminates holder-in-due-course protections for assignees of

certain high cost mortgages [as defined by 15 U.S.C. §1602(aa)] and renders them subject to all claims and

defenses that the borrower could assert against the original lender." Vandenbroeck v. Contimortgage Corp.,

53 F.Supp.2d 965, 968 (W.D. Mich. 1999)(emphasis added); Bryant, 197 F.Supp.2d at 1364-65. The operation and effect of § 1641(d) is unmistakable.

15 U.S.C. § 1641(d) in part provides:

(1) ... Any person who purchases or is otherwise assigned a mortgage referred to in [15 U.S.C.

§ 1602(aa)] shall be subject to all claims and defenses with respect to the mortgage that the

consumer could assert against the creditor of the mortgage, unless the purchaser or assignee

demonstrates, [**35] by a preponderance of the evidence, that a reasonable person exercising ordinary due diligence, could not determine, based on the documentation required by this

[title]... that the [*18] mortgage was a mortgage referred to in [15 U.S.C. § 1602 (aa)] ...

Page 11

2002 U.S. Dist. Ct. Briefs 714286, *; 2006 U.S. Dist. Ct. Briefs LEXIS 2628, **

(Emphasis added.)

Section 1641(d)(1) provides in clear and unambiguous terms that assignees like the RFC are subject to

all claims and defenses under any law that a borrower could have asserted against the original lender. Vandenbroeck, 53 F.Supp.2d at 968. Hence, it does not matter that the RFC Defendants may not have initially

charged the excessive fees and closing costs on which these claims are based. And certainly since acquiring

the loans, the assignees have collected and received (and continue to collect and receive) interest on the

loans.

Holding assignees liable for these Banks' "tainted" loans effectuates the intention of Congress with regard to the consumer real estate loans at issue as is made clear by the legislative history of § 1641(d). In describing its enactment, Congress stated as follows:

9. Assignee Liability

The bill eliminates "holder-in-due-course" [**36] protections for assignees of High Cost

Mortgages. Assignees of High Cost Mortgages are subject to all claims and defenses, whether

under Truth in Lending or other law, that could be raised against the original lender...

By imposing assignee liability, the Committee seeks to ensure that the High Cost Mortgage

market polices itself. Unscrupulous lenders were limited in the past by their own capital resources. Today, however, with loans sold on a regular basis, an unscrupulous player can create

havoc in a community by selling loans as fast as they are originated. Providing assignee liability will halt the flow of capital to such lenders.

S.Rep. No. 169, 103d Cong., 2d Sess. 5 (1994) reprinted in 1994 U.S.C.C.A.N. 1881, 1912 (emphasis added).

For these reasons, the Court should waste little time in rejecting any contention that the assignee liability

imposed by § 1641(d) does not subject an assignee to liability as to affirmative claims of a borrower as asserted in this and the other related and consolidated matter.

[*19] B. THE CORE DISCLOSURES: AMOUNT FINANCED, FINANCE CHARGE AND

ANNUAL PERCENTAGE RATE

1. These Interrelated Disclosures [**37]

Are At The Core of TILA.

The "material disclosures" required by TILA are defined as:

the disclosure, as required by this subchapter, of the annual percentage rate, the method of determining the finance charge and the balance upon which a finance charge will be imposed, the

amount of the finance charge, the amount to be financed, the total of payments, the number and

amount of payments, the due dates or periods of payments scheduled to repay the indebtedness,

and the disclosures required by section 1639 (a) [HOEPA] of this title.

15 U.S.C. § 1602(u)(emphasis added); see also 12 U.S.C. § 226.23(a), at n.48 (defining "material disclosures" for purposes of rescission to include those required by 12 C.F.R. § 226.32(c) and (d)). These terms

reflect Congress' desire to avoid "informational overload" by focusing on the terms "most relevant to a consumer's initial credit decision." Household Credit Services, Inc. v. Pfennig, 541 U.S. 232, 243 (2004); 12

C.F.R. § 226.17(a)(1).

Page 12

2002 U.S. Dist. Ct. Briefs 714286, *; 2006 U.S. Dist. Ct. Briefs LEXIS 2628, **

The purpose of having an accurate price tag, using a standardized definition and calculation

method, is [**38] two-fold. First, it enables consumers to make informed decisions about using credit. Seeing the cold, hard figures helps consumer determine whether to use credit or not.

When credit costs are high, it encourages consumer restraint: some consumers will decide that

paying cash, deferring debt entirely, or scaling back are preferable to paying high interest rates.

In this respect, Truth in Lending serves a public purpose in addition to a private one: the macroeconomic purpose of enhancing economic stabilization. Second, it provides consumers with

the information necessary to comparison shop for the best terms. In this respect, it serves the

interests of both consumers and legitimate lenders. Consumers are given information necessary

to make an informed choice and are protected from "fraudulent, deceitful or grossly misleading

information." "Ethical and efficient" credit providers are protected from deceitful competitors,

thus competition is invigorated. Accordingly, the comparison shopping role has both a public

and private purpose, as well, it is designed to curb practices that impede the effective operation

of market forces.

National Consumer Law Center, Truth in Lending, [**39] at § 3.1.1, at p.55 (5th ed. 2003)(citing authorities); see also Mourning v. Family Publications Service, 411 U.S. 356, 377 (1972)("the Truth in Lending Act

reflects a transition in Congressional policy from a philosophy of 'let the [*20] buyer beware' to one of 'let

the seller disclose.'"); Williams v. Chartwell Financial Services, Ltd., 204 F.3d 748, 751 (7th Cir.

2000)("Congress enacted TILA to ensure that consumers receive accurate information from creditors in a

precise and uniform manner that allows them to compare the cost of credit."); Saunders Affidavit at PP

30-38.

Simply stated, the Finance Charge and Annual Percentage Rate provide a consistent and "all-inclusive"

calculation of the true cost of a loan that takes into account not only the terms of a loan, such as the interest

rate and number of payments, but those additional fees and charges imposed on a loan that are not reflected

in the interest rate. See Truth in Lending, supra, at §§ 3.2.1-.2.

a. Finance Charge and Amount Financed

The term "Finance Charge" is defined at 15 U.S.C. § 1605 and 12 C.F.R. § 226.4. It represents "the cost

of consumer [**40] credit as a dollar amount." 12 C.F.R. § 226.4(a). TILA defines the Finance Charge "as

the sum of all charges, payable directly or indirectly by the person to whom the credit is extended, and imposed directly or indirectly by the creditor as an incident to the extension of credit." 15 U.S.C. § 1605(a); 12

C.F.R. § 226.4(a). In other words, it's all the charges and costs the borrower pays for the use of the lent funds

including all interest paid. By its plain language, TILA presumes that all settlement charges are included in

the Finance Charge. Certain specified charges, however, can be excluded such as bona fide and reasonable

title charges. 12 C.F.R. § 226.4(c)(7). It is the Banks' improper exclusion of title charges from the finance

charge and resulting misstatements of the APR disclosure, all in violation of TILA and HOEPA, which are at

issue.

Directly related and mutually exclusive to the Finance Charge is the "Amount Financed" on a loan. The

"amount financed" is "the amount of credit of which the consumer has actual [*21] use." 15 U.S.C. §

1638(a)(2)(A). The Amount Financed is calculated by adding the charges that are not [**41] finance

charges but that are financed by the creditor and then subtracting the "prepaid finance charges," which are the

charges that are included in the finance charge and the borrower pays for them by withholding them from the

proceeds of their loan. 15 U.S.C. § 1638(a)(2)(A); 12 C.F.R. § 226.18(b); Truth in Lending, at § 4.6.2.5. This

term tells the borrower "those legitimate components of the obligation which are advanced by the lender or

paid to others on the borrower's behalf." Truth in Lending, at § 3.2.2. Because a borrower does not have "ac-

Page 13

2002 U.S. Dist. Ct. Briefs 714286, *; 2006 U.S. Dist. Ct. Briefs LEXIS 2628, **

tual use" of bogus or required third party charges, such charges cannot be part of the "amount financed" under TILA. Gibson v. LTD, Inc., 434 F.3d 275, 283-85 (4th Cir. 2006)("If a lender has no basis for including a

charge ... as part of the purchaser's amount financed, the disclosure of the amount financed' is erroneous, and

the error gives rise to TILA liability."); 15 U.S.C. §§ 1605(a), 1638(a)(2)(A); 12 C.F.R. §§ 226.4(a)(2),

226.18(b). n5

n5 TILA also has special rules that are used to determine whether charges by third parties are excluded from or included within the Finance Charge. 15 U.S.C. § 1605(a); 12 C.F.R. § 226.4(a)(1)-(2). In

general, the rules state:

[i]f the creditor requires the use of a closing agent, fees charged by the closing agent are

included in the finance charge only if the creditor requires the particular service, requires

the imposition of the charge, or retains a portion of the charge.

Official Staff Commentary to § 226.4, at P (4)(a)(2). Such "required" fees are included in the Finance

Charge because they are more relevant to determining the "true cost of credit" than other fees. See

Household Credit Services, Inc. v. Pfennig, 541 U.S. 232, 243 (2004). Moreover, these "required"

charges must be included in the Finance Charge because a fundamental purpose of TILA is to promote

competition among lenders. 15 U.S.C. § 1601(a). If a lender requires its borrower to incur certain third

party charges, then the only true means to promote competition amongst lenders is to include those

charges in the disclosures which inform the borrowers of the true cost of their loans. In this case, because the fees for the title examinations and the title abstracts were required by the banks, they should

be included in the Finance Charge under this interpretation of TILA. Mourning v. Family Publications

Service, Inc., 411 U.S. 356, 364 (1972)("The Truth in Lending Act was designed to remedy the problems which had developed. The House Committee on Banking and Currency reported, in regard to the

then proposed legislation: '(B)y requiring all creditors to disclose credit information in a uniform

manner, and by requiring all additional mandatory charges imposed by the creditor as an incident to

credit be included in the computation of the applicable percentage rate, the American consumer will

be given the information he needs to compare the cost of credit and to make the best informed decision on the use of credit.'")(emphasis added); Anderson Bros. Ford v. Valencia, 452 U.S. 205, 220

n.17 (1981)(same). While not focused on in this brief, this is arguably another basis for finding TILA

and HOEPA violations against the Banks. This basis of liability can be further explored through discovery of the relationship between the Banks and what appear to be their captive title companies like

USA Title and Title America including what percentage, if any, of the title company charges the

Banks retained.

[**42]

[*22] b. Annual Percentage Rate (APR)

The APR is "the measure of the cost of credit, expressed as a yearly rate, that relates the amount and

timing of value received by the consumer to the amount and timing of payments made." 12 C.F.R. §

226.22(e); see also 226.18(e)("the costs of your credit at a yearly rate"). Because the APR is affected by the

calculations of the Finance Charge and Amount Financed, it can only be calculated after those calculations

are made. 15 U.S.C. § 1606(a); 12 C.F.R. § 226.22(a); Appendix J to 12 C.F.R. Part 226. The finance charge

and APR are interrelated in that an inaccurate finance charge necessarily makes the APR disclosure inaccurate. Id.

Page 14

2002 U.S. Dist. Ct. Briefs 714286, *; 2006 U.S. Dist. Ct. Briefs LEXIS 2628, **

2. Determining the Finance Charge, Amount Financed and the APR

a. Finance Charge and Amount Financed

As noted above, its is presumed that all closing costs (plus all interest) make up the Finance Charge.

Certain charges may, however, be excluded from the Finance Charge if the creditor can show they meet an

exception to this presumption. See 15 U.S.C. § 1605; 12 CF.R. § 226.4 (a)-(c). "[A]ny exclusions from the

definition of the [**43] finance charge should be narrowly construed in order to protect the consumer and

encourage robust disclosure. See Bizier v. Globe Financial Servs., Inc., 654 F.2d 1, 3 (1st Cir. 1981); Hickey

v. Great W. Mortgage Corp. 1995 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 405, 30-31 (D. Ill. 1995); Buford v. American Finance

Co., 333 F. Supp. 1243, 1247 (N.D. Ga. 1971);; Equity Plus Consumer Finance & Mortgage v. Howes 861

P.2d 214 (N.M. 1993). The burden to prove compliance with the TILA rests on the creditor. Brannam v.

Huntington Mortgage, 287 F.3d 601 (6th Cir. 2002); see also Wright v. Tower Loan of Mississippi, Inc. 679

F.2d 436, 444 (5th Cir. 1982). Those fees that the creditor demonstrates meet the exclusion are then included

as part of the Amount Financed. 15 U.S.C. § 1638(a)(2)(A); 12 C.F.R. § 226.18(b). Thus, determining

whether a listed closing cost is part of [*23] the Finance Charge or the Amount Financed involves analysis

of the exclusionary rules of the Finance Charge.

This analysis entails making certain the charge is a listed exclusionary charge and that the charge [**44]

is bona fide and reasonable. Brannam, 287 F.3d at 606 ("To be excluded from the finance charge, the fees

must not only be the right types, but they must also be bona fide and reasonable in amount.'"); 15 U.S.C.

§1605(e); 12 C.F.R. § 226.4(c)(7); see also Official Staff Commentary to § 226.4, at P (4)(c)(7)("in all cases,

charges excluded under §226.4(c)(7) must be bona fide and reasonable."); see also Saunders Affidavit at PP

41-42. In this regard, it has long been held that exclusions from the Finance Charge are strictly construed:

As already noted, the design of the Act was to remove from the individual creditors the right to

determine the "finance charge" and to establish by statute and regulation a uniform method for

such determination so that consumers could "comparison shop" by looking at a single "price

tag"-the "annual percentage rate." Given the purpose of the Act and the thrust of its provisions,

the court concludes that only those charges specifically exempted from inclusion in the "finance charge" by statute or regulation may be excluded from it. The notary fees involved in

these cases are not specifically [**45] exempted, therefore defendants were required to include them in the "finance charge." Although the fee was only $ 1.00, its amount is immaterial

as far as the disclosure requirements of the Act are concerned.

Buford v. American Finance Co., 333 F.Supp. 1243, 1247 (N.D. Ga. 1971).

In a transaction secured by real estate, as in this case, the first question in the analysis asks whether the

charge at issue is specifically set forth in 15 U.S.C. § 1605(e) or 12 C.F.R. §226.4(c)(7) as an exclusion from

the Finance Charge. These excludible charges include:

(i) Fees for title examination, abstract of title, title insurance, property survey, and similar purposes.

(ii) Fees for preparing loan-related documents, such as deeds, mortgages, and reconveyance or

settlement documents.

(iii) Notary and credit report fees.

Page 15

2002 U.S. Dist. Ct. Briefs 714286, *; 2006 U.S. Dist. Ct. Briefs LEXIS 2628, **

[*24] (iv) Property appraisal fees or fees for inspections to assess the value or condition of

the property if the service is performed prior to closing, including fees related to pest infestation or flood hazard determinations.

(v) Amounts required to be paid into escrow or trustee accounts [**46] if the amounts would

not otherwise be included in the finance charge.

12 C.F.R. § 226.4(c)(7).

If the charge at issue is listed in 15 U.S.C. § 1605(e) and/or 12 C.F.R. § 226.4(c)(7), then the second

question in the analysis asks whether the charges for the fees were "bona fide" and "reasonable." 12 C.F.R. §

226.4(c)(7). This analysis as to the HUD-1 Line 1102 (title abstract) and Line 1103 (title exam) charges are

the crux issue as to the Objectors' TILA and HOEPA claims. n6

n6 If the charge at issue is not listed, then there is a third question as to whether the fee considered for

exclusion is a fee identified in other provisions of 15 U.S.C. § 1605(d) and (e) and/or 12 C.F.R. §

226.4(c), (d) or (e). These provisions provide another set of exceptions to inclusion in the Finance

Charge. Objectors note that the Banks routinely excluded from the Finance Charge "application fees"

that are made to all applicants for credit (12 C.F.R. § 226.4(c)(1)) and "taxes and fees prescribed by

law that actually are or will be paid to public officials for determining the existence of or for perfecting, releasing, or satisfying a security interest." 15 U.S.C. § 1605(d)(1); 12 C.F.R. § 226.4(e)(1)). Although there is much evidence to suggest that the latter charges were often marked up on the borrowers' loans and, therefore, making some or all of the charge not bona fide or not reasonable, these closing costs and fees are not at included in the analysis at this point.

The Objectors further note that the Banks also routinely charged fees for "document reviews" performed by the title companies in Line 1112 of the HUD-1 Settlement Statements that were improperly

excluded from the Finance Charge calculation. Regardless of the legitimacy or reasonableness of such

fees, they cannot be excluded from the Finance Charge under 12 C.F.R. § 226.4(c)(7) because they are

not listed as excludable fees. The Objectors do not at this time include these fees in the TILA and

HOEPA viability analysis because in most, if not all instances, the APR is materially misstated as to

all borrowers using the Line 1103 title examination charge and the Line 1102 markup only. As to

those few borrowers who may be on the fence with only the Line 1102 markup and the Line 1103

charge, inclusion of the remainder of Line 1102 and/or the entirety of Line 1112 (if excluded) in the

Finance Charge would be more than sufficient to establish a APR violation in every loan of the class.

[**47]

b. Annual Percentage Rate (APR)

Regulation Z permits lenders to calculate the APR by two methods: (1) the "actuarial" method and (2)

the "U.S. Method". 12 C.F.R. § 226.22(a). While these methods of calculations are different, they will invariably yield the same APR on closed-end mortgage loans "when payment intervals are equal." See Official

Staff Commentary, § 226.22(a)(1)-1; Truth in Lending, at § 4.6.4.3. Performing the calculation by hand is

difficult, see, e.g., 12 C.F.R. Part [*25] 226, Appendix J, and virtually all lenders use computer programs

or APR calculators to ensure the accuracy of their calculations. Truth in Lending, at § 4.6.4.3. The programs

used by the Objectors and Ms. Saunders to calculate the APRs on the Objectors' loans are called Consumer

Law Math, Version 2.2.0, which is a program created by Custom Legal Software and used by the National

Consumer Law Center, and APRWIN, Version 5.0.0, which is the APR calculator used by the Office of the

Page 16

2002 U.S. Dist. Ct. Briefs 714286, *; 2006 U.S. Dist. Ct. Briefs LEXIS 2628, **

Comptroller of the Currency. Both are standard and commonly used programs used for this purpose. See

Saunders Affidavit, at P 62, n.42; Hodes Affidavit (Exhibit 5), at P 17.

In this matter, [**48] Objectors do not contend that the banks' method of calculating the APR was erroneous. Rather (and to repeat), the Objectors claim that Finance Charge is inaccurate under the provisions of

TILA. The inaccuracy necessarily results in an inaccurate APR and, accordingly, the misstatement of the

APR violates HOEPA.

3. Tolerances for Accuracy

TILA and HOEPA set forth specific rules which set forth allowable "tolerances" for inaccurate disclosures. The lender may raise these tolerances as affirmative defenses to the borrowers' claims that a disclosure

was inaccurate. See Inge v. Rock Financial Corp., 281 F.3d 613, 621-22 (6th Cir. 2002)("The overriding

policy behind the TILA, however, remains focused on consumer protection; the responsibility to allege the

minimal nature of the disclosure, and therefore the absence of a violation, should rest with the lender.");

Saunders Affidavit at PP 50-53. As explained below, the Banks' inaccurate disclosures exceed the allowable

tolerances.

[*26] a. Finance Charge and Amount Financed

As a general rule, the Finance Charge is "treated as accurate" if the lender establishes that the Disclosed

Finance Charge does [**49] not vary from the Actual Finance Charge by more than $ 100 or that the Finance Charge was overstated. 15 U.S.C. § 1605(f); 12 C.F.R. § 226.18(d)(1). Since the Amount Financed is

mutually exclusive to the Finance Charge, the Disclosed Amount Financed will be deemed accurate if the

Disclosed Finance Charge is deemed accurate. Id.

b. APR

As a general rule, the APR is considered as accurate if the Disclosed APR is within 1/8% more or less of

the actual APR. 15 U.S.C. § 1606(c); 12 C.F.R. § 226.22(a)(3). The APR is also considered accurate if an

APR disclosure error is caused by an error calculating the Finance Charge or in certain circumstances where

the Finance Charge is within the tolerance level but the APR is not. See 12 C.F.R. §§ 226.22(a)(4) and (5).

This unique rule is not at issue here because the Finance Charge was materially understated and inaccurate in

all instances.

c. Rescission

i. General Rule

For non-HOEPA loans, the borrower may only rescind their loan under the provisions of 15 U.S.C. §

1635 (discussed below) if the Finance Charge is understated by one-half of one [**50] percent (1/2%) the

face amount of the promissory note. 15 U.S.C. § 1605(f)(2); 12 C.F.R. § 226.23(g)(1).

ii. HOEPA Loans

For HOEPA loans, however, the borrower may rescind their loan if the APR is understated by 1/8%.

Accuracy of annual percentage rate. For purposes of § 226.32, the annual percentage rate shall

be considered accurate, and may be used in determining [*27] whether a transaction is covered by § 226.32, if it is accurate according to the requirements and within the tolerances under

§ 226.22. The finance charge tolerances for rescission under § 226.23(g) or (h) shall not apply

for this purpose.

Page 17

2002 U.S. Dist. Ct. Briefs 714286, *; 2006 U.S. Dist. Ct. Briefs LEXIS 2628, **

12 C.F.R. § 226.31(g). Because §226.23(g) and (h) set forth the one half of one percent tolerance for

non-HOEPA loans, the general rule allowing rescission for disclosures that are inaccurate by more than 1/8%

in § 226.22(a)(2) applies by the plain language of the regulation. This is confirmed by a reading of §

226.22(a)(4), which only incorporates the 1/2% tolerance through a reference to § 226.23(g) and (h). Saunders Affidavit at PP 50-53. This reduced tolerance serves to effectuate HOEPA's protections by providing

[**51] HOEPA borrowers with an expanded rescission right.

The APR is also considered accurate for purposes of rescission of a HOEPA loan if an APR disclosure

error is caused by an error calculating the Finance Charge or in certain circumstances (not applicable here)

where the Finance Charge is within the tolerance level but the APR is not. See 12 C.F.R. §§ 226.22(a)(4) and

(5); 12 C.F.R. § 226.31(g)(1).

d. Foreclosure

If the lender has initiated foreclosure, the tolerance is only $ 35.00 for an under disclosure of the Finance

Charge. 15 U.S.C. § 1635(i)(2); 12 C.F.R. § 226.23(h)(2)(i). There is no tolerance in this situation if the

lender failed to include a mortgage broker fee in the finance charge calculation. Id.

4. Timing of Disclosures

a. TILA

TILA requires that the material disclosures set forth at 15 U.S.C. § 1638 and 12 C.F.R. § 226.18 are to be

made "before the credit is extended." 15 U.S.C. § 1638(b)(1). Regulation Z states that the lender must make

these disclosures "before consummation of the transaction." 12 [*28] C.F.R. § 226.17(b). "Consummation" is the "time that [**52] a consumer becomes contractually obligated on a credit transaction." 12

C.F.R. § 226.2 (a)(13).

b. HOEPA

Creditors making HOEPA loans are, however, required to make the HOEPA disclosures to borrowers at

least three business days before the consummation, or closing, of the loan. See 15 U.S.C. § 1639; 12 C.F.R.

§§ 226.31(c); 226.32(c). These disclosures include the three-sentence "Miranda" warning concerning the

significance of having a mortgage on one's home, the APR, and the amount of the regular monthly payment

on the loan. 15 U.S.C. § 1639(a); 12 C.F.R. § 226.32(c).

C. OTHER REQUIREMENTS OF HOEPA

1. Prohibition on Prepayment Penalties

If a loan is covered by HOEPA, it may not contain a prepayment penalty unless a strict exception to

HOEPA is established. 15 U.S.C. § 1639(c); 12 C.F.R. § 226.32(d)(6)-(7). One such exception (i.e. one circumstance where a prepayment penalty can be a term of the note) is when the refinancing occurs with a

lender that is not the original lender or an affiliate of that lender. See 15 U.S.C. § 1639(c)(2)(B); 12 C.F.

[**53] R. § 226.32(d)(7)(ii). McIntosh v. Irwin Union Bank and Trust, Co., 215 F.R.D. 26, 30 (D. Mass.

2003); In re Rodrigues, 278 B.R. 683, 690 (D.R.I. 2003). This prohibition is designed to address the fact that

fear of a prepayment penalty keeps borrowers from refinancing and getting out from under the burden of an

expensive HOEPA loan. Saunders Affidavit at P 85. Many of the Note forms utilized by the Banks contain

provisions providing for prepayment penalties but which do not disclose the HOEPA restriction that a prepayment penalty may be collected "only to a prepayment made with amounts obtained by the [*29] consumer by means other than a refinancing by the creditor under the mortgage, or an affiliate of that creditor."

15 U.S.C. § 1639(c)(2)(B).

Under HOEPA, the inclusion of a prohibited term in the mortgage, such as a prepayment penalty, "shall

be deemed a failure to deliver the material disclosures required under this subchapter, for the purpose of section 1635 of this title." 15 U.S.C. § 1639(j). Thus, those borrowers whose loans contain illegal prepayment

Page 18

2002 U.S. Dist. Ct. Briefs 714286, *; 2006 U.S. Dist. Ct. Briefs LEXIS 2628, **

penalties are, regardless of [**54] the inaccuracy of the disclosures or the timing of the disclosures, entitled

to damages under 15 U.S.C. § 1640(a)(4) and may rescind their loans under 15 U.S.C. § 1635.

D. CONSUMER REMEDIES FOR VIOLATIONS OF TILA AND HOEPA

1. Strict Liability

As the Third Circuit recently noted in this very case, violations of TILA give rise to strict liability. In re

Community Bank of Northern Virginia, 418 F.3d 277, 305-06 (3rd Cir. 2005)("TILA achieves its remedial

goals by a system of strict liability."). The Third Circuit has previously held that:

TILA achieves its remedial goals by a system of strict liability in favor of the consumers when

mandated disclosures have not been made. A creditor who fails to comply with TILA in any

respect is liable to the consumer under the statute regardless of the nature of the violation or the

creditor's intent. "[O]nce the court finds a violation, no matter how technical, it has no discretion with respect to liability."

In re Porter, 961 F.2d 1066, 1078 (3rd Cir. 1992) (emphasis added) (quoting Smith v. Fidelity Consumer

Discount Co., 898 F.2d 896, 898 (3rd Cir. 1990)); [**55] Smith v. Cash Store Mgmt., 195 F.3d 325, 328

(7th Cir. 1999); Purtle v. Eldridge Auto Sales, Inc., 91 F.3d 797, 801 (6th Cir. 1996); Grant v. Imperial Motors, 539 F.2d 506, 510 (5th Cir. 1976); see also Mars v. Spartanburg Chrysler Plymouth, Inc., 713 F.2d 65,

67 (4th Cir. 1983). ("To insure that the consumer is protected, as Congress envisioned, requires that the provisions of the Act be absolutely complied [*30] with and strictly enforced"); In re Ramirez, 329 B.R. 727,

731-32 (D. Kan. 2005)("To encourage lender compliance, TILA violations are measured by a strict liability

standard, so even minor or technical violations impose liability upon the creditor. The consumer-borrower

can prevail in a TILA suit without showing that he or she suffered any actual damage as a result of the creditor's violation."). Thus, it is unnecessary to explore any actual damages or reliance as to a borrower who received inaccurate disclosures or who did not timely receive the required HOEPA disclosures.

"First, the alleged technical deficiencies of the document bear no relationship to the achievement of the [**56] Congressional purposes of the Truth in Lending Act." Dzadovsky v. Lyons

Ford Sales, Inc., 452 F.Supp. 606, 611 (W.D.Pa.1978). This conclusion was based on appellant's failure to claim that she was actually deceived by the alleged inaccuracies or that they related to her inability to repay her debt. Id. at 607, 608.

We are unable to accept this rationale because it suggests the requirement of financial loss before a borrower may bring an action. It is clear, however, that such injury need not be alleged.

One of the legislative purposes of the Act is to enable consumers to compare various available

credit terms. Any proven violation of the disclosure requirements of the Act is presumed to injure a borrower by frustrating that purpose.

Dzadovsky v. Lyons Ford Sales, Inc., 593 F.2d 538, 539 (3rd Cir. 1979)(emphasis added).

2. Statutory Damage Remedies

A creditor's failure to make the "material disclosures" required by TILA and HOEPA, or to make those

disclosures at the time required by HOEPA, gives rise to substantial damages as set forth in 15 U.S.C. § 1640

which include actual and [**57] statutory damages. 15 U.S.C. § 1640(a); see also Koons Buick Pontiac

GMC, Inc. v. Nigh, 543 U.S. 50, 54 (2004). These same violations also provide the aggrieved borrower (here,

Page 19

2002 U.S. Dist. Ct. Briefs 714286, *; 2006 U.S. Dist. Ct. Briefs LEXIS 2628, **

each class member) with a statutory right to rescind their loan as well as providing for injunctive and declaratory relief. 15 U.S.C. § 1635; 12 C.F.R. § 226.23.

[*31] Section 1640(a) provides as follows:

Individual or class action for damages; amount of award; factors determining amount of award

Except as otherwise provided in this section, any creditor who fails to comply with any requirement imposed under this part, including any requirement under section 1635 of this title,

or part D or E of this subchapter with respect to any person is liable to such person in an

amount equal to the sum of-

(1) any actual damage sustained by such person as a result of the failure;

(2)

(A)

(i) in the case of an individual action twice the amount of any finance charge in

connection with the transaction,

(ii) in the case of an individual action relating to a consumer lease under part E of

this subchapter, 25 per [**58] centum of the total amount of monthly payments

under the lease, except that the liability under this subparagraph shall not be less

than $ 100 nor greater than $ 1,000, or

(iii) in the case of an individual action relating to a credit transaction not under an

open end credit plan that is secured by real property or a dwelling, not less than $

200 or greater than $ 2,000; or

(B) in the case of a class action, such amount as the court may allow, except that

as to each member of the class no minimum recovery shall be applicable, and the

total recovery under this subparagraph in any class action or series of class actions arising out of the same failure to comply by the same creditor shall not be

more than the lesser of $ 500,000 or 1 per centum of the net worth of the creditor;

(3) in the case of any successful action to enforce the foregoing liability or in any

action in which a person is determined to have a right of rescission under section

1635 of this title, the costs of the action, together with a reasonable attorney's fee

as determined by the court; and

(4) in the case of a failure to comply with any requirement under section 1639 of

this title, an amount equal [**59] to the sum of all finance [*32] charges and

fees paid by the consumer, unless the creditor demonstrates that the failure to

comply is not material.

***

15 U.S.C. § 1640(a).

Page 20

2002 U.S. Dist. Ct. Briefs 714286, *; 2006 U.S. Dist. Ct. Briefs LEXIS 2628, **

The specific damages a borrower is entitled to under § 1640 are as follows:

a. Actual Damages

First, § 1640(a)(1) allows the class members their actual damages. The Truth in Lending manual suggests that a "correction of the error" standard under § 1640(b) applies for actual damages under TILA. Id. at

§ 8.5.5.3. Under this analysis, all bogus, unreasonable and marked up fees should be refunded as restitution

to the borrowers. In re Russell, 72 B.R. 855, 863-64 (E.D. Pa. 1987); Goldman v. First National Bank of

Chicago, 532 F.2d 10, 15 (5th Cir. 1976). The Truth in Lending manual also suggests that creditors should

be held, as a matter of contract, to the understated Finance Charges and APR. Id. at § 8.5.5.5.

b. Statutory Damages

Sections 1640(a)(2), (3) and (4) provide for "statutory" awards of damages for non-HOEPA TILA violations and HOEPA violations. Section 1640(a)(2) is applicable to all violations [**60] and limits the statutory award to the range of $ 200 to $ 2,000 where the borrowers' principal residence secures the loan. In a

class action, the class is limited to a statutory award of $ 500,000 per creditor "for the same failure to comply" with the requirements of TILA and HOEPA. 15 U.S.C. § 1640(a)(2)(B).

Also, prevailing class members are entitled to their costs and attorneys' fees. 15 U.S.C. § 1640(a)(3).

[*33] c. "Enhanced" HOEPA Damages

For violations of HOEPA, in addition to the actual damages under § 1640(a)(1) and the statutory damages under § 1640(a)(2) and (3), each class member is entitled to "an amount equal to the sum of all finance

charges and fees paid by the consumer, unless the creditor demonstrates that the failure to comply is not material." n7 15 U.S.C. § 1640(a)(4); see also In re Williams, 291 B.R. 636, 664 (E.D. Pa. 2003) ("The statutory

damage provision contained in § 1640(a) was amended to increase the total award to the consumer in the

case of HOEPA violations") (citing Newton v. United Companies Financial Corp., 24 F.Supp.2d 444, 451

(E.D. Pa. 1998). [**61] Statutory damages in HOEPA class actions are not limited since the limitation on

class actions applies only to the penalty awarded under § 1640(a)(2)(B). There is no cap on the damages under § 1640(a)(4). These HOEPA damages are sometimes called "Enhanced Damages" and will be so referred

to by Objectors.

n7 "Material disclosures" are defined at 15 U.S.C. § 1602(u) to include "the annual percentage rate,...

the amount of the finance charge, the amount to be financed, ... and the [HOEPA] disclosures required

by section 1639(a) of this title." Thus, the failure to provide the borrower an accurate APR is a violation of § 1639 giving rise to these "enhanced" HOEPA damages.

Consequently, if a creditor violates HOEPA's disclosure requirements and/or if that creditor includes

prohibited terms in a HOEPA loan, or engages in abusive practices, then that creditor and its assignees will

not only be subject to civil liability and damages under 15 U.S.C. § 1640(a)(1), [**62] (2) and (3), but

they will also be liable for enhanced damages under § 1640(a)(4) for those additional HOEPA violations.

Accordingly, because the Banks, among other things, understated the APR disclosure given to the borrowers,

the Banks as well as the Assignee Defendants are liable to the class members for "all finance charges and

fees" that were paid by class members in addition to the TILA statutory damages and rescission. 15 U.S.C.

§§ 1635(g); 1640(a)(4), (g).

[*34] 3. TILA and HOEPA Provide For Cumulative Remedies and Multiple Assessments of

HOEPA's "Enhanced Damages"

Page 21

2002 U.S. Dist. Ct. Briefs 714286, *; 2006 U.S. Dist. Ct. Briefs LEXIS 2628, **

Again, the statutory provisions governing a borrowers' damages under TILA and HOEPA are set forth at

15 U.S.C. § 1640(a). The exceptions to § 1640(a) are provided at §§ 1640(d) and (g). Section 1640(d) provides that in the case where there are multiple obligors on a loan the statutory damages allowed under §

1640(a)(2) are limited to one recovery. In § 1640(g), TILA limits recovery for "multiple failures to disclose"

to a single recovery:

The multiple failure to disclose to any person any information required under this part or part D

or E of [**63] this subchapter to be disclosed in connection with a single account under an

open end consumer credit plan, other single consumer credit sale, consumer loan, consumer

lease, or other extension of consumer credit, shall entitle the person to a single recovery under

this section but continued failure to disclose after a recovery has been granted shall give rise to

rights to additional recoveries. This subsection does not bar any remedy permitted by section

1635 of this title.

15 U.S.C. § 1640(g).

What this means is that under TILA's plain language, the single-recovery rule of § 1640(g) applies only

to failures to disclose the information in § 1602(u), and not other violations of TILA or HOEPA, such as

form and timing requirements. See Belmont v. Associates Nat. Bank (Delaware), 219 F.Supp.2d 340, 345-46

(E.D. N.Y. 2002), 219 F.Supp.2d at 345-46; see also Brown v. SCI Funeral Services of Florida, Inc., 212

F.R.D. 602, 606-07 (S.D. Fla. 2003)("the Court is not persuaded that the provision in § 1640 limiting statutory damages for violations of disclosure requirements applies to violations of timing and form requirements,

[**64] such that Plaintiffs are precluded from asserting a class claim for statutory damages based on § 1632

or § 1638(b)."); Lozada v. Dale Baker Oldsmobile, Inc., 145 F.Supp.2d 878, 885-89 (W.D. Mich.2001)("A

requirement that a disclosure be made in a certain manner and at a certain time does not fall within the previously stated definition of a 'disclosure.'"). Accordingly, the failure [*35] of the Banks to provide the

HOEPA Notice three business days before closing or the inclusion of an improper prepayment penalty are

"form and timing" or "substantive" violations of HOEPA giving rise to a second recovery of enhanced

HOEPA damages. n8