Unit 1 Answers to Recommended End-of-Chapter

advertisement

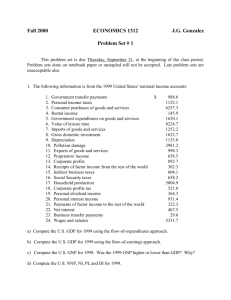

Unit 1 Answers to Recommended End-of-Chapter-Problems Chapter 1 Review Questions 1. Both total output and output per worker have risen strongly over time in the United States. Output itself has grown by a factor of 100 in the last 133 years. Output per worker is now six times as great as it was in 1900. These changes have led to a much higher standard of living today. 2. The business cycle refers to the short-run movements (expansions and recessions) of economic activity. The unemployment rate rises in recessions and declines in expansions. The unemployment rate never reaches zero, even at the peak of an expansion. 3. A period of inflation is one in which prices (on average) are rising over time. Deflation occurs when prices are falling on average over time. Before World War II, prices tended to rise during war periods and fall after the wars ended; over the long run, the price level remained fairly constant. Since World War II, however, prices have risen fairly steadily. 4. The budget deficit is the annual excess of government spending over tax collections. The U.S. federal government has been most likely to run deficits during wars. From the early 1980s to the mid-1990s, deficits were very large, even without a major war. The U.S. government ran surpluses for several years, from 1998 to 2001. 5. The trade deficit is the amount by which imports exceed exports; the trade surplus is the amount by which exports exceed imports, so it is the negative of the trade deficit. In recent years the United States has had huge trade deficits. But from 1900 to 1970, the United States mostly had trade surpluses. 7. The steps in developing and testing an economic model or theory are: (1) state the research question; (2) make provisional assumptions that describe the economic setting and the behavior of the economic actors; (3) work out the implications of the theory; (4) conduct an empirical analysis to compare the implications of the theory with the data; and (5) evaluate the results of your comparisons. The criteria for a useful theory or model are that (1) it has reasonable and realistic assumptions; (2) it is understandable and manageable enough for studying real problems; (3) its implications can be tested empirically using real-world data; and (4) its implications are consistent with the data. 8. Yes, it is possible for economists to agree about the effects of a policy (that is, to agree on the positive analysis of the policy), but to disagree about the policy’s desirability (normative analysis). For example, suppose economists agreed that reducing inflation to zero within the next year would cause a recession (positive analysis). Some economists might argue that inflation should be reduced, because they prefer low inflation even at the cost of higher unemployment. Others would argue that inflation isn’t as harmful to people as unemployment is, and would oppose such a policy. This is normative analysis, as it involves a value judgment about what policy should be. 9. Classicals see wage and price adjustment occurring rapidly, while Keynesians think that wages and prices adjust only slowly when the economy is out of equilibrium. The classical theory implies that unemployment will not persist because wages and prices adjust to bring the economy rapidly back to equilibrium. But if Keynesian theory is correct, then the slow response of wages and prices means that unemployment may persist for long periods of time unless the government intervenes. 10. Stagflation was a combination of stagnation (high unemployment) and inflation in the 1970s. It changed economists’ views because the Keynesian approach couldn’t explain stagflation satisfactorily. Chapter 1 Numerical Problems 1. (a) Average labor productivity is output divided by employment: 2005: 12,000 tons of potatoes divided by 1000 workers 12 tons of potatoes per worker 2006: 14,300 tons of potatoes divided by 1100 workers 13 tons of potatoes per worker (b) The growth rate of average labor productivity is [(13/12) – 1] 100% 8.33%. (c) The unemployment rate is: 2005: (100 unemployed/1100 workers) 100% 9.1% 2006: (50 unemployed/1150 workers) 100% 4.3% (d) The inflation rate is [(2.5/2) – 1] 100% 25%. 2. The answers to this problem will vary depending on the current date. The answers here are based on the August 2006 Survey of Current Business, Tables 1.1.5 and 3.2. Numbers are at annual rates in billions of dollars. GDP Exports Imports Federal receipts Federal expenditures a. Exports/GDP Imports/GDP Trade imbalance/GDP b. Federal receipts/GDP Federal expenditures/GDP Deficit/GDP 11,712.5 1,178.1 1,791.4 2,001.0 2,383.0 12,455.8 1,303.1 2,019.9 2,246.8 2,555.9 13,008.4 1,405.4 2,170.6 2,473.2 2,637.9 10.1% 15.3% –5.2% 10.5% 16.2% –5.8% 10.8% 16.7% –5.9% 17.1% 20.3% –3.3% 18.0% 20.5% –2.5% 19.0% 20.3% –1.3% Chapter 1 Analytical Problems 1. Yes, average labor productivity can fall even when total output is rising. Average labor productivity is total output divided by employment. So average labor productivity can fall if output and employment are both rising but employment is rising faster. Yes, the unemployment rate can also rise even though total output is rising. This can occur a number of different ways. For example, average labor productivity might be rising with employment constant, so that output is rising; but the labor force may be increasing as well, so that the unemployment rate is rising. Or average labor productivity might be constant, and both employment and unemployment could rise at the same time because of an increase in the labor force, with the number of unemployed rising by a greater percentage. 2. Just because prices were lower in 1890 than they were in 2006 does not mean that people were better off back then. People’s incomes have risen much faster than prices have risen over the last 100 years, so they are better off today in terms of real income. 4. (a) Positive. This statement tells what will happen, not what should happen. (b) Positive. Even though it is about income-distribution issues, it is a statement of fact, not opinion. If the statement said “The payroll tax should be reduced because it . . . ,” then it would be a normative statement. (c) Normative. Saying taxes are too high suggests that they should be lower. (d) Positive. Says what will happen as a consequence of an action, not what should be done. (e) Normative. This is a statement of preference about policies. Chapter 2 Chapter 2 Review Questions 1. The three approaches to national income accounting are the product approach, the income approach, and the expenditure approach. They all give the same answer because they are designed that way; any entry based on one approach has an entry in the other approaches with the same value. Whenever output is produced and sold, its production is counted in the product approach, its sale is counted in the expenditure approach, and the funds received by the seller are counted in the income approach. 3. Intermediate goods and services are used up in producing other goods in the same period (year) in which they were produced, while final goods and services are those that are purchased by consumers or are capital goods that are used to produce future output. The distinction is important, because we want to count only the value of final goods produced in the economy, not the value of goods produced each step along the way. 4. GNP is the market value of final goods and services newly produced by domestic factors of production during the current period, whereas GDP is production taking place within a country. Thus, GNP differs from GDP when foreign factors are used to produce output in a country, or when domestic factors are used to produce output in another country. GDP GNP – NFP, where NFP net factor payments from abroad, which equals income paid to domestic factors of production by the rest of the world minus income paid to foreign factors of production by the domestic economy. A country that employs many foreign workers will likely have negative NFP, so GDP will be higher than GNP. 5. The four components of spending are consumption, investment, government purchases, and net exports. Imports must be subtracted, because they are produced abroad and we want GDP to count only those goods and services produced within the country. For example, suppose a car built in Japan is imported into the United States. The car counts as consumption spending in U.S. GDP, but is subtracted as an import as well, so on net it does not affect U.S. GDP. However, it is counted in Japan’s GDP as an export. 7. National wealth is the total wealth of the residents of a country, and consists of its domestic physical assets and net foreign assets. Wealth is important because the long-run economic well-being of a country depends on it. National wealth is related to national saving because national saving is the flow of additions to the stock of national wealth. 8. Real GDP is the useful concept for figuring out a country’s growth performance. Nominal GDP may rise because of increases in prices rather than growth in real output. 9. The CPI is a price index that is calculated as the value of a fixed set of consumer goods and services at current prices divided by the value of the fixed set at base-year prices. CPI inflation is the growth rate of the CPI. CPI inflation overstates true inflation because it is hard to measure changes in quality, and because the price index doesn’t account for substitution away from goods that become relatively more expensive towards goods that become relatively cheaper. 10. The nominal interest rate is the rate at which the nominal (or dollar) value of an asset increases over time. The real interest rate is the rate at which the real value or purchasing power of an asset increases over time, and is equal to the nominal interest rate minus the inflation rate. The expected real interest rate is the rate at which the real value of an asset is expected to increase over time. It is equal to the nominal interest rate minus the expected inflation rate. The concept that is most important to borrowers and lenders is the expected real interest rate, because it affects their decisions to borrow or lend. Chapter 2 Numerical Problems 2. 5. (a) Furniture made in North Carolina that is bought by consumers counts as consumption, so consumption increases by $6 billion, investment is unchanged, government purchases are unchanged, net exports are unchanged, and GDP increases by $6 billion. (b) Furniture made in Sweden that is bought by consumers counts as consumption and imports, so consumption increases by $6 billion, investment is unchanged, government purchases are unchanged, net exports fall by $6 billion, and GDP is unchanged. (c) Furniture made in North Carolina that is bought by businesses counts as investment, so consumption is unchanged, investment increases by $6 billion, government purchases are unchanged, net exports are unchanged, and GDP increases by $6 billion. (d) Furniture made in Sweden that is bought by businesses counts as investment and imports, so consumption is unchanged, investment increases by $6 billion, government purchases are unchanged, net exports decline by $6 billion, and GDP is unchanged. Given data: I 40, G 30, GNP 200, CA –20 NX NFP, T 60, TR 25, INT 15, NFP 7 –9 –2. Since GDP GNP – NFP, GDP 200 – (–2) 202 Y. Since NX NFP CA, NX CA – NFP –20 – (–2) –18. Since Y C I G NX, C Y – (I G NX) 202 – (40 30 (–18)) 150. Spvt (Y NFP – T TR INT) – C (202 (–2) – 60 25 15) –150 30. Sgovt (T – TR – INT) – G (60 – 25 – 15) – 30 –10. S Spvt Sgovt 30 (–10) 20. (a) Consumption 150 (b) Net exports –18 (c) GDP 202 (d) Net factor payments from abroad –2 (e) Private saving 30 (f) Government saving –10 (g) National saving 20 6. Base-year quantities at current-year prices at base-year prices 3000 $3 $ 9,000 6000 $2 $12,000 8000 $5 $40,000 $61,000 3000 $2 $ 6,000 6000 $3 $18,000 8000 $4 $32,000 $56,000 Apples Bananas Oranges Total Current-year quantities at current-year prices Apples Bananas Oranges Total 4,000 $3 $ 12,000 14,000 $2 $ 28,000 32,000 $5 $160,000 $200,000 at base-year prices 4,000 $2 $ 8,000 14,000 $3 $ 42,000 32,000 $4 $128,000 $178,000 (a) Nominal GDP is just the dollar value of production in a year at prices in that year. Nominal GDP is $56 thousand in the base year and $200 thousand in the current year. Nominal GDP grew 257% between the base year and the current year: [($200,000/$56,000) – 1] 100% 257%. (b) Real GDP is calculated by finding the value of production in each year at base-year prices. Thus, from the table above, real GDP is $56,000 in the base year and $178,000 in the current year. In percentage terms, real GDP increases from the base year to the current year by [($178,000/$56,000) – 1] 100% 218%. (c) The GDP deflator is the ratio of nominal GDP to real GDP. In the base year, nominal GDP equals real GDP, so the GDP deflator is 1. In the current year, the GDP deflator is $200,000/$178,000 1.124. Thus the GDP deflator changes by [(1.124/1) – 1] 100% 12.4% from the base year to the current year. (d) Nominal GDP rose 257%, prices rose 12.4%, and real GDP rose 218%, so most of the increase in nominal GDP is because of the increase in real output, not prices. Notice that the quantity of oranges quadrupled and the quantity of bananas more than doubled. 7. Calculating inflation rates: 1929–30: [(50.0/51.3) – 1] 100% –2.5% 1930–31: [(45.6/50.0) – 1] 100% –8.8% 1931–32: [(40.9/45.6) – 1] 100% –10.3% 1932–33: [(38.8/40.9) – 1] 100% –5.1% These all show deflation (prices are declining over time), whereas recently we have had nothing but inflation (prices rising over time). 8. The nominal interest rate is [(545/500) – 1] 100% 9%. The inflation rate is [(214/200) – 1] 100% 7%. So the real interest rate is 2% (9% nominal rate – 7% inflation rate). Expected inflation was only [(210/200) – 1] 100% 5%, so the expected real interest rate was 4% (9% nominal rate – 5% expected inflation rate). Chapter 2 Analytical Problems 2. National saving does not rise because of the switch to CheapCall because although consumption spending declines by $2 million, so have total expenditures (GDP), which equal total income. Since income and spending both declined by the same amount, national saving is unchanged. 3. (a) The problem in a planned economy is that prices do not measure market value. When the price of an item is too low, then goods are really more expensive than their listed price suggests—we should include in their market value the value of time spent by consumers waiting to make purchases. Because the item’s value exceeds its cost, measured GDP is too low. When the price of an item is too high, goods stocked on the shelves may be valued too highly. This results in an overvaluation of firms’ inventories, so that measured GDP is too high. A possible strategy for dealing with this problem is to have GDP analysts estimate what the market price should be (perhaps by looking at prices of the same goods in market economies) and use this “shadow” price in the GDP calculations. (b) The goods and services that people produce at home are not counted in the GDP figures because they are not sold on the market, making their value difficult to measure. One way to do it might be to look at the standard of living relative to a market economy, and estimate what income it would take in a market economy to support that standard of living. Chapter 3 Answers Chapter 3 Review Questions 1. A production function shows how much output can be produced with a given amount of capital and labor. The production function can shift due to supply shocks, which affect overall productivity. Examples include changes in energy supplies, technological breakthroughs, and management practices. Besides knowing the production function, you must also know the quantities of capital and labor the economy has. 2. The upward slope of the production function means that any additional inputs of capital or labor produce more output. The fact that the slope declines as we move from left to right illustrates the idea of diminishing marginal productivity. For a fixed amount of capital, additional workers each add less additional output as the number of workers increases. For a fixed number of workers, additional capital adds less additional output as the amount of capital increases. 3. The marginal product of capital (MPK) is the output produced per unit of additional capital. The MPK can be shown graphically using the production function. For a fixed level of labor, plot the output provided by different levels of capital; this is the production function. The MPK is just the slope of the production function. 4. The marginal revenue product of labor represents the benefit to a firm of hiring an additional worker, while the nominal wage is the cost. Comparing the benefit to the cost, the firm will hire additional workers as long as the marginal revenue product of labor exceeds the nominal wage, since doing so increases profits. Profits will be at their highest when the marginal revenue product of labor just equals the nominal wage. The same condition can be expressed in real terms by dividing through by the price of the good. The marginal revenue product of labor equals the marginal product of labor times the price of the good. The nominal wage equals the real wage times the price of the good. Dividing each of these through by the price of the good means that an equivalent profitmaximizing condition is the marginal product of labor equals the real wage. 5. The MPN curve shows the marginal product of labor at each level of employment. It is related to the production function because the marginal product of labor is equal to the slope of the production function (where output is plotted against employment). The MPN curve is related to labor demand, because firms hire workers up to the point at which the real wage equals the marginal product of labor. So the labor demand curve is identical to the MPN curve, except that the vertical axis is the real wage instead of the marginal product of labor. 6. A temporary increase in the real wage increases the amount of labor supplied because the substitution effect is larger than the income effect. The substitution effect arises because a higher real wage raises the benefit of additional work for a worker. The income effect is small because the increase in the real wage is temporary, so it doesn’t change the worker’s income very much, thus the worker won’t reduce time spent working very much. A permanent increase in the real wage, however, has a much larger income effect, since a worker’s lifetime income is changed significantly. The income effect may be so large that it exceeds the substitution effect, causing the worker to reduce time spent working. 7. The aggregate labor supply curve relates labor supply and the real wage. The principal factors shifting the aggregate labor supply curve are wealth, the expected future real wage, the country’s working-age population, or changes in the social or legal environment that lead to changes in labor force participation. Increases in wealth or the expected future real wage shift the aggregate labor supply curve to the left. Increases in the working-age population or in labor-force participation shift the aggregate labor supply curve to the right. 8. Full-employment output is the level of output that firms supply when wages and prices in the economy have fully adjusted; in the classical model of the labor market, this occurs when the labor market is in equilibrium. When labor supply increases, full-employment output increases, as there is now more labor available to produce output. When a beneficial supply shock occurs, then the same quantities of labor and capital produce more output, so fullemployment output rises. Furthermore, a beneficial supply shock increases the demand for labor at each real wage and leads to an increase in the equilibrium level of employment, which also increases output. 9. The classical model of the labor market assumes that any worker who wants to work at the equilibrium real wage can find a job, so it is not very useful for studying unemployment. 10. The labor force consists of all employed and unemployed workers. The unemployment rate is the fraction of the labor force that is unemployed. The participation rate is the fraction of the adult population that is in the labor force. The employment ratio is the fraction of the adult population that is employed. 11. An unemployment spell is a period of time that a person is continuously unemployed. Duration is the length of time of an unemployment spell. Two seemingly contradictory facts are that most unemployment spells have a short duration and that most people who are unemployed at a particular time are experiencing spells with long durations. These can be reconciled by realizing that there may be a lot of people with short spells and a few people with long spells. On any given date, a survey finds a fairly long average duration for the unemployed, because of the people with long spells. For example, suppose that each week one person becomes unemployed for one week, so there are fifty-two such short unemployment spells during the year. And suppose that there are four people who are unemployed all year, so there are four long unemployment spells during the year. In any given week five people are unemployed: one unemployed person has a spell of one week, while four have spells of a year. So most spells have a short duration (fifty-two short spells compared to four long spells), but most people who are unemployed at a given time are experiencing spells with long duration (one short spell compared to four long spells). 12. Frictional unemployment arises as workers and firms search to find matches. A certain amount of frictional unemployment is necessary, because it is not always possible to find the right match right away. For example, an unemployed banker may not want to take a job flipping hamburgers if he or she cannot find another banking job right away, because the match would be very poor. By remaining unemployed and continuing to search for a more suitable job, the banker is likely to make a better match. That will be better both for the banker (since the salary is likely to be higher) and for society as a whole (since the better match means greater productivity in the economy). 13. Structural unemployment occurs when people suffer long spells of unemployment or are chronically unemployed (with many spells of unemployment). Structural unemployment arises when the number of potential workers with low skill levels exceeds the number of jobs requiring low skill levels, or when the economy undergoes structural change, when workers who lose their jobs in shrinking industries may have difficulty finding new jobs. 14. The natural rate of unemployment is the rate of unemployment that prevails when output and employment are at their full-employment levels. The natural rate of unemployment is equal to the amount of frictional unemployment plus structural unemployment. Cyclical unemployment is the difference between the actual rate of unemployment and the natural rate of unemployment. When cyclical unemployment is negative, output and employment exceed their full-employment levels. 15. Okun’s Law is a rule of thumb that tells how much output falls when the unemployment rate rises. It is written either in terms of the levels of output and unemployment, as in Eq. (3.5), ( Y – Y)/ Y 2 (u – u ), or in terms of changes in output and unemployment, as in Eq. (3.6), Y/Y 3 – 2 u. Since the Okun’s law coefficient is 2, a 2 percentage point increase in the unemployment rate causes output to decline by 4%. Chapter 3 Numerical Problems 3. (a) N 1 2 3 4 5 6 Y 8 15 21 26 30 33 MPN 8 7 6 5 4 3 MRPN (P 5) 40 35 30 25 20 15 MRPN (P 10) 80 70 60 50 40 30 (b) P $5. (1) W $38. Hire one worker, since MRPN ($40) is greater than W ($38) at N 1. Do not hire two workers, since MRPN ($35) is less than W ($38) at N 2. (2) W $27. Hire three workers, since MRPN ($30) is greater than W ($27) at N 3. Do not hire four workers, since MRPN ($25) is less than W ($27) at N 4. (3) W $22. Hire four workers, since MRPN ($25) is greater than W ($22) at N 4. Do not hire five workers, since MRPN ($20) is less than W ($22) at N 5. (c) Figure 3.10 plots the relationship between labor demand and the nominal wage. This graph is different from a labor demand curve because a labor demand curve shows the relationship between labor demand and the real wage. Figure 3.11 shows the labor demand curve. Figure 3.10 Figure 3.11 (d) P $10. The table in part a shows the MRPN for each N. At W $38, the firm should hire five workers. MRPN ($40) is greater than W ($38) at N 5. The firm shouldn’t hire six workers, since MRPN ($30) is less than W ($38) at N 6. With five workers, output is 30 widgets, compared to 8 widgets in part a when the firm hired only one worker. So the increase in the price of the product increases the firm’s labor demand and output. (e) If output doubles, MPN doubles, so MRPN doubles. The MRPN is the same as it was in part d when the price doubled. So labor demand is the same as it was in part d. But the output produced by five workers now doubles to 60 widgets. (f) Since MRPN P MPN, then a doubling of either P or MPN leads to a doubling of MRPN. Since labor demand is chosen by setting MRPN equal to W, the choice is the same, whether P doubles or MPN doubles. 5. (a) If the lump-sum tax is increased, there’s an income effect on labor supply, not a substitution effect (since the real wage isn’t changed). An increase in the lump-sum tax reduces a worker’s wealth, so labor supply increases. (b) If T 35, then NS 22 12w (2 35) 92 12 w. Labor demand is given by w MPN 309 – 2N, or 2N 309 – w, so N 154.5 – w/2. Setting labor supply equal to labor demand gives 154.5 – w/2 92 12w, so 62.5 12.5w, thus w 62.5/12.5 5. With w 5, N 92 (12 5) 152. (c) Since the equilibrium real wage is below the minimum wage, the minimum wage is binding. With w 7, N 154.5 – 7/2 151.0. Note that NS 92 (12 7) 176, so NS > N and there is unemployment. 7. (a) At any date, 25 people are unemployed: 5 who have lost their jobs at the start of the month and 20 who have lost their jobs either on January 1 or July 1. The unemployment rate is 25/500 5%. (b) Each month, 5 people have one-month spells. Every six months, 20 people have sixmonth spells. The total number of spells during the year is (5 12) (20 2) 100. Sixty of the spells (60% of all spells) last one month, while 40 of the spells (40% of all spells) last six months. (c) The average duration of a spell is (0.60 1 month) (0.40 6 months) 3 months. (d) On any given date, there are 25 people unemployed. Twenty of them (80%) have long spells of unemployment, while 5 of them (20%) have short spells. Chapter 3 Analytical Problems 2. (a) An increase in the number of immigrants increases the labor force, increasing employment and increasing full-employment output. (b) If energy supplies become depleted, this is likely to reduce productivity, because energy is a factor of production. So the reduction in energy supplies reduces full-employment output. (c) Better education raises future productivity and output, but has no effect on current fullemployment output. (d) This reduction in the capital stock reduces full-employment output (although it may very well increase welfare).