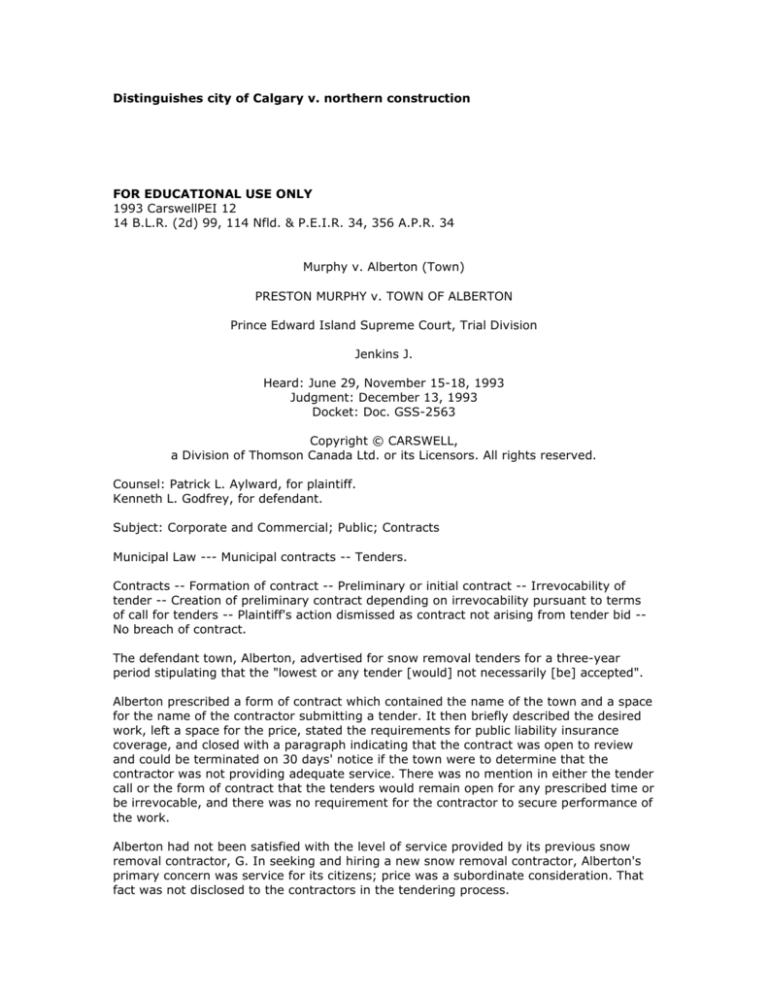

Distinguishes city of Calgary v. northern construction

FOR EDUCATIONAL USE ONLY

1993 CarswellPEI 12

14 B.L.R. (2d) 99, 114 Nfld. & P.E.I.R. 34, 356 A.P.R. 34

Murphy v. Alberton (Town)

PRESTON MURPHY v. TOWN OF ALBERTON

Prince Edward Island Supreme Court, Trial Division

Jenkins J.

Heard: June 29, November 15-18, 1993

Judgment: December 13, 1993

Docket: Doc. GSS-2563

Copyright © CARSWELL,

a Division of Thomson Canada Ltd. or its Licensors. All rights reserved.

Counsel: Patrick L. Aylward, for plaintiff.

Kenneth L. Godfrey, for defendant.

Subject: Corporate and Commercial; Public; Contracts

Municipal Law --- Municipal contracts -- Tenders.

Contracts -- Formation of contract -- Preliminary or initial contract -- Irrevocability of

tender -- Creation of preliminary contract depending on irrevocability pursuant to terms

of call for tenders -- Plaintiff's action dismissed as contract not arising from tender bid -No breach of contract.

The defendant town, Alberton, advertised for snow removal tenders for a three-year

period stipulating that the "lowest or any tender [would] not necessarily [be] accepted".

Alberton prescribed a form of contract which contained the name of the town and a space

for the name of the contractor submitting a tender. It then briefly described the desired

work, left a space for the price, stated the requirements for public liability insurance

coverage, and closed with a paragraph indicating that the contract was open to review

and could be terminated on 30 days' notice if the town were to determine that the

contractor was not providing adequate service. There was no mention in either the tender

call or the form of contract that the tenders would remain open for any prescribed time or

be irrevocable, and there was no requirement for the contractor to secure performance of

the work.

Alberton had not been satisfied with the level of service provided by its previous snow

removal contractor, G. In seeking and hiring a new snow removal contractor, Alberton's

primary concern was service for its citizens; price was a subordinate consideration. That

fact was not disclosed to the contractors in the tendering process.

M submitted a tender within the appointed time. Two other tenders were received, from

G and O. M's tender was the lowest bid. O's tender document did not contain on its face

any name and it was not signed.

In considering the competing bids, Alberton considered factors such as operator

capability, equipment availability and quality, and the anticipated level of service of the

contractors. Alberton awarded the contract to O, the highest bidder. Alberton did not give

M any reason for rejecting his low bid.

M brought an action for damages, claiming loss of profits resulting from a breach of

contract by Alberton.

Held:

The action was dismissed.

Traditionally, a request for tenders is viewed as an invitation to treat the tender as an

offer, and the award of the contract as an acceptance. Until accepted, an offer, unless

made irrevocable, creates no legal relationship and may lapse or be withdrawn at any

time before acceptance at the will of the offeror.

In the tendering process, it is possible for a preliminary or initial contract, which can lead

to the formation of a final contract, to be created. However, such a preliminary contract

is not created in every tendering process. Whether such a preliminary contract will be

created depends upon whether the tender submitted by the contractor is irrevocable

pursuant to the terms of the call for tenders. Accordingly, the circumstances of each case

must be examined to determine whether the owner's invitation to submit tenders is

merely an invitation to treat or whether it is an offer to enter into a preliminary contract.

Under the terms and conditions of Alberton's call for tenders, the tenders were not

required to be irrevocable, the contractors being at liberty to withdraw their tenders at

any time before Alberton communicated acceptance of a tender. Submission of the bid by

M did not, in and of itself, create any obligation on the part of M. Consequently, a

preliminary or initial contract did not arise, and thus there was no basis for M's claim of

breach of contract. In the alternative, if a preliminary contract between M and Alberton

had arisen, then M would have been entitled to damages.

In considering the rights and obligations which arise under such preliminary contracts in

the tendering process, the courts should pursue the policy objective of protecting the

integrity of the bidding system where, under the law of contracts, it is possible to do so.

A balanced approach of promoting this objective while also adhering to established

principles of contract law is to recognize that (1) the parties are at liberty to contract on

whatever terms that they choose; (2) to the extent that an owner wishes to reserve

privileges, he or she must do so in clear terms; and (3) an owner is not entitled to rely

upon secret or undisclosed preferences, or to proceed arbitrarily in choosing from among

the bidders.

While an owner has the right to include in the tender documents stipulations and

restrictions on the rights of bidders and to reserve privileges to itself, the owner

nevertheless owes a general duty to treat all bidders fairly, and an owner does not have

the right when considering competing tenders to rely upon undisclosed terms and

conditions. In this regard, the presence of the standard privilege clause "lowest or any

tender not necessarily accepted" in the invitation for tenders reserves conditionally to the

owner the privilege to decide not to proceed with the work at all, but does not allow the

owner to choose comparatively among the bidders based on criteria that have not been

disclosed to the bidders or award to another bidder or another person something other

than the contract for tender.

To allow such a privilege clause, which was used by Alberton to prevail, would be to

annihilate the objective of fairness in the tendering process. It would allow Alberton to

decline to enter into a contract with any of the contractors for good or bona fide reason,

but it does not entitle Alberton to arbitrarily reject the lowest qualified bid and award the

work to a higher bidder based on terms or criteria undisclosed in the tender documents.

The owner must disclose to the industry in its tender documentation all the requirements

which it expects the contractors to meet. The owner cannot impose something that it has

not indicated. An owner can publish its invitation for bids, or prepare its contract

documents, such that a bid does not give rise to a preliminary contract. Subject to public

policy considerations, an owner can include whatever term it wishes in its contract

documents in order to reserve the privilege of determining and choosing a successful

contractor on criteria other than price. An owner can reserve the right to choose not to

proceed at all with the work. Invitations and tender documents can be designed and kept

short and simple, or be made long and complex, depending on the intended evaluation

process and the scope of the proposed work. In any event, the principles of contract law

prevail, interpreted in the context of the fairness established in Ron Engineering &

Construction (Eastern) Ltd. v. Ontario.

General custom in bidding, and particularly local customs, can result in implied

contractual rights. A custom in commercial bidding which exists in Prince Edward Island is

that unsigned bids are considered informal, and consequently invalid. Here, the bid by O

was not signed, and thus it was invalid. As such, if there had been a preliminary contract

with M, Alberton would have been obliged to reject O's bid as informal.

In considering the measure of damages flowing from a breach of a preliminary contract in

the tendering process, an inference can be drawn from the evidence that an owner would

have accepted the tender of the lowest bidder. Had the preliminary contract with M

arisen, Alberton would have accepted M's bid as the lowest bid. As such, the measure of

damages would have been the cost of preparation of M's bid and the estimated loss of

profit on the snow removal contract.

Cases considered:

A.W. MacPhail Ltd. v. Kelson (1989), 34 C.L.R. 1, 96 N.B.R. (2d) 330, 243 A.P.R. 330

(C.A.) -- distinguished

Acme Building & Construction Ltd. v. Newcastle (Town) (1990), 38 C.L.R. 56 (Ont. Dist.

Ct.), affirmed (1992), 2 C.L.R. (2d) 308 (Ont. C.A.), leave to appeal to S.C.C. refused

(1993), 151 N.R. 394 (note), 63 O.A.C. 399 (note) -- not followed

Arctic Co-operatives Ltd. v. Sigyamiut Ltd. (Receiver of) (1991), 5 C.B.R. (3d) 271

(N.W.T. S.C.) -- considered

Bate Equipment Ltd. v. Ellis-Don Ltd. (1992), 2 C.L.R. (2d) 157, 132 A.R. 161 (Q.B.) -distinguished

Ben Bruinsma & Sons Ltd. v. Chatham (City) (1984), 29 B.L.R. 148, 11 C.L.R. 37 (Ont.

H.C.) -- distinguished

Best Cleaners & Contractors Ltd. v. Canada, [1985] 2 F.C. 293, 58 N.R. 295 (C.A.) -applied

Calgary (City) v. Northern Construction Co., [1987] 2 S.C.R. 757, 80 N.R. 394, 82 A.R.

395, 56 Alta. L.R. (2d) 193, [1988] 2 W.W.R. 193 -- distinguished

Canamerican Auto Lease & Rental Ltd. v. Canada (March 4, 1985) (Fed. T.D.)

[unreported] -- considered

Cartwright & Crickmore Ltd. v. MacInnes, [1931] S.C.R. 425, [1932] 3 D.L.R. 693 -referred to

Chinook Aggregates Ltd. v. Abbotsford Municipal District (1989), 40 B.C.L.R. (2d) 345, 35

C.L.R. 241, [1990] 1 W.W.R. 624 (C.A.) [amended (November 29, 1989), Doc.

CA008497 (B.C. C.A.)] -- distinguished

Elgin Construction Co. v. Russell (Township) (1987), 24 C.L.R. 253 (Ont. H.C.) -- referred

to

Ellis-Don Construction Ltd. v. Canada (Minister of Public Works) (1992), 1 C.L.R. (2d)

193, 54 F.T.R. 42 -- referred to

Georgia Construction Co. v. Pacific Great Eastern Railway, [1929] S.C.R. 630, 36 C.R.C.

23, [1929] 4 D.L.R. 161 -- referred to

Hawes v. Sherwood-Parkdale Metro Junior Hockey Club Inc. (1991), 88 D.L.R. (4th) 439,

96 Nfld. & P.E.I.R. 169, 305 A.P.R. 169 (P.E.I. C.A.)considered

Kawneer Co. v. Bank of Canada (1982), 40 O.R. (2d) 275 (C.A.) -- referred to

Kencor Holdings Ltd. v. Saskatchewan, [1991] 6 W.W.R. 717, 96 Sask. R. 171, 6 Admin.

L.R. (2d) 110 (Q.B.) -- distinguished

M.S.K. Financial Services Ltd. v. Alberta (1987), 23 C.L.R. 172, (sub nom. M.S.K.

Financial Services Ltd. v. Alberta (Minister of Public Works, Supply & Services)) (Alta.

M.C.) -- applied

Martselos Services Ltd. v. Arctic College (1992), 5 B.L.R. (2d) 204 (N.W.T. S.C.)

[reversed [1994] 3 W.W.R. 73, [1994] N.W.T.R. 36, 12 C.L.R. (2d) 208, 111 D.L.R. (4th)

65 (C.A.)] -- distinguished

Megatech Contracting Ltd. v. Ottawa-Carleton (Regional Municipality) (sub nom.

Megatech Contracting Ltd. v. Carleton (Regional Municipality)) (1989), 34 C.L.R. 35, 68

O.R. (2d) 503 (H.C.) -- not followed

Northern Construction Co. v. Gloge Heating & Plumbing Ltd., 32 B.L.R. 142, 67 A.R. 150,

42 Alta. L.R. (2d) 326, [1986] 2 W.W.R. 649, 19 C.L.R. 281, 27 D.L.R. (4th) 264 (C.A.) - distinguished

Peddlesden Ltd. v. Liddell Construction Ltd. (1981), 32 B.C.L.R. 392, (sub nom. M.J.

Peddlesden Ltd. v. Liddell Construction Ltd.) 128 D.L.R. (3d) 360 (S.C.) -- considered

Power Agencies Co. v. Newfoundland Hospital & Nursing Home Assn. (1991), 44 C.L.R.

255, 90 Nfld. & P.E.I.R. 64, 280 A.P.R. 64 (Nfld. T.D.) -- referred to

Protec Installations Ltd. v. Aberdeen Construction Ltd. (1993), 6 C.L.R. (2d) 143 (B.C.

S.C.) -- distinguished

Ron Engineering & Construction (Eastern) Ltd. v. Ontario, [1981] 1 S.C.R. 111, 13 B.L.R.

72, 119 D.L.R. (3d) 267, 35 N.R. 40 -- distinguished

Scott Steel (Ottawa) Ltd. v. R.J. Nicol Construction (1975) Ltd. (March 3, 1993), Docs.

450/89, 419/93 (Ont. Div. Ct.) -- distinguished

Slave Lake (Town) v. Appleton Construction Ltd. (1987), 53 Alta. L.R. (2d) 177, 25 C.L.R.

311, 80 A.R. 276 (Q.B.) -- distinguished

Tercon Contractors Ltd. v. British Columbia (1993), 9 C.L.R. (2d) 197 (B.C. S.C.) -considered

Whistler Service Park Ltd. v. Whistler (Resort Municipality) (1990), 50 M.P.L.R. 233, 41

C.L.R. 132 (B.C. S.C.) -- not followed

Zutphen Brothers Construction Ltd. v. Nova Scotia (Attorney General) (1993), 12 C.L.R.

(2d) 111, 125 N.S.R. (2d) 34, 349 A.P.R. 34 (S.C.) -- referred to

Words and phrases considered:

contract -- "A contract is entered into by one person making an offer, and another

accepting it. This simple basic situation may take on many varied and sophisticated

guises, but every contractual situation can, in the last analysis, be reduced to these

simple terms. An offer, once it has been accepted, becomes a contract and creates a

legal relationship between the parties, and cannot thereafter be withdrawn. Until

accepted, an offer, unless made irrevocable, creates no legal relationship and may lapse

or be withdrawn at any time before acceptance at the will of the offeror; such withdrawal,

to be effective, must be communicated to the offeree ..."

Action for damages for loss of profits from breach of contract.

Jenkins J.:

1

The plaintiff ("Murphy") claims damages against the defendant ("the Town") for loss

of profits resulting from a breach of contract following a snow removal tender.

Facts

2

In 1990, the Town advertised by newspaper for snow removal tenders for a threeyear period. The advertisement stipulated "Lowest or any tender not necessarily

accepted"; and advised that further information was available by contacting a designated

town councilor. Murphy obtained this further information and then within the appointed

time submitted a tender on the proposed form of contract provided by the Town. The

prescribed form was straightforward. It contained the name of the Town and a space for

the name of the contractor ("Company"). It then set out the Town's desire to have its "...

streets plowed of snow as well as its parking lots and having snow removal in certain

areas within the Town..." It briefly described the work, left a space for the price, stated

the requirement for public liability insurance coverage, and closed with the following

paragraph:

4. This contract is open to review and may be terminated at (30) days notice if it is

determined that the Company is not providing adequate service. A determination of

inadequate service must be made by an independent third party acceptable to each of

the principal parties.

At the bottom, it contained spaces for execution by both the Town and the contractor.

There was no mention in either the tender call or form of contract of the tender

remaining open for any prescribed time, or being irrevocable, and there was no

requirement for the contractor to secure performance of the work.

3

Murphy submitted the low bid. The Town received three bids, as follows:

Year 1

-------

Year 2

-------

Year 3

-------

MURPHY

$31,500

$32,000

$32,500

GORDON

30,250

33,000

36,350

Total

-----

$99,950

O'MEARA

40,000

41,000

42,000

The O'Meara document did not contain on its face any name and was not signed,

although it was contained in a sealed envelope that was imprinted with O'Meara's name.

4

The tender terms did not require the submission of an equipment list. Gordon's

tender was accompanied by an equipment list. After opening the tenders, the Town

council requested the other bidders, Murphy and O'Meara, to submit lists of their

equipment. Both complied.

5

The Town had not been satisfied with the level of service provided by its previous

snow removal contractor, Gordon. In seeking and hiring a new snow removal contractor,

the Town's primary concern was service for its citizens; price was a subordinate

consideration. This criteria was not disclosed to the bidders in the bidding process. The

Town council assessed the bids on a comparative basis based on what it considered to be

relevant considerations that would serve the best interests of the Town. It considered

operator capability, equipment availability and quality, and the anticipated level of service

of the bidders. The Town then awarded a contract to O'Meara, the highest bidder. The

Town did not give Murphy any reason for rejecting his low bid. Immediately following its

decision, council thanked Murphy in writing for submitting his tender. The letter advised:

We wish to inform you that your tender has not been accepted but encourage you to offer

at another time.

Submissions

6

Murphy submits that when the Town chose to utilize the tendering process it

contractually obligated itself to sign the formal contract with the lowest qualified bidder

for the work being tendered out. In failing to do so, and instead entering into a formal

contract with a third party for the work being tendered out, the Town breached that

contractual obligation. He submits that the Town was obligated to enter the snow

removal contract with him; and that the words "lowest or any tender not necessarily

accepted" contained in the advertisement do not release the Town from that obligation.

Murphy suggests that this case is about the integrity of the public tendering process and

whether and how the courts will protect it. He claims as damages his loss of profits over

the three-year term of the snow removal contract.

7

The Town responds that it did not owe any contractual obligation to Murphy to enter

into a contract for snow removal. At most, the Town owed the plaintiff a duty to treat him

fairly, and the Town is entitled to rely upon its intent expressed by the clear words in the

call for tenders. The Town denies the existence of any custom that would require it to

award the contract to the low bidder, and asserts that any such custom could not, in any

event, override the express words of the tender call. The Town asserts that Murphy was

not qualified, and that the Town is entitled to exclude unqualified bidders. The Town

further asserts that if Murphy was qualified, then it was entitled to choose between the

bidders based on the best interests of the Town. The Town submits should there be a

finding of liability, then Murphy did not incur the damages claimed. The Town suggests

that the question for this Court is whether the state of the law is such that a municipality

is required to hire a second-rate service just because it advertises for tenders in a

newspaper.

Disposition

8

I have decided that, in the circumstances, no contract arose between the parties.

Therefore, there is no basis for Murphy's claim for damages. Accordingly, his claim is

dismissed.

Reasons: No Contract

9

Ron Engineering & Construction (Eastern) Ltd. v. Ontario, [1981] 1 S.C.R. 111, 119

D.L.R. (3d) 267 (S.C.C.) ("Ron Engineering") significantly affected the traditional notions

regarding the appropriate application of the law of contract to the tendering process.

However, Ron Engineering does not emasculate the law of contracts so as to create in

every tendering process a preliminary or initial contract: Canamerican Auto Lease &

Rental Ltd. v. Canada, (unreported, March 4, 1985, Fed. T.D.), ("Canamerican Auto

Lease"). It is the irrevocability of the bid made in accordance with the tender conditions

that forms the preliminary contract, or contract A, between the owner and the bidder:

Ron Engineering, at pp. 272, 274.

10

Traditionally, a request for tender was viewed as an invitation to treat the tender as

an offer, and the award as an acceptance. A contract is entered into by one person

making an offer, and another accepting it. This simple basic situation may take on many

varied and sophisticated guises, but every contractual situation can, in the last analysis,

be reduced to these simple terms. An offer, once it has been accepted, becomes a

contract and creates a legal relationship between the parties, and cannot thereafter be

withdrawn. Until accepted, an offer, unless made irrevocable, creates no legal

relationship and may lapse or be withdrawn at any time before acceptance at the will of

the offeror; such withdrawal, to be effective, must be communicated to the offeree:

Goldsmith on Canadian Building Contracts, 4th ed. (1988, rev. 1993), pp. 1-15-1-16.

11

Tenders are used in a number of types of contracts. Goldsmith contains a full and

concise discussion of the current state of the law of tendering since Ron Engineering, at

pp. 1-19-1-22 [at rev. 1994 1-20-1-22]:

The purpose of the system is to provide competition, and thereby to reduce costs,

although it by no means follows that the lowest tender will necessarily result in the

cheapest job. Many a "low" bidder has found that his prices have been too low and has

ended up in financial difficulties, which have inevitably resulted in additional costs to the

owner, whose right to recover them from the defaulting contractor is usually academic.

Accordingly, the prudent owner will consider not only the amount of the bid, but also the

experience and capability of the contractor, and whether the bid is realistic in the

circumstances of the case. In order to eliminate unrealistic tenders, some public

authorities and corporate owners require tenderers to be pre-qualified.

Since the tendering procedure is intended to provide the owner with the cheapest way of

having his particular construction completed ...

It is important to appreciate the precise legal nature of a tender. Whether it is submitted

in response to an invitation to tender or not, a tender is nothing more or less than an

offer to carry out the work specified therein on and subject to the terms and conditions

stated at the price quoted. A tender may consist of a short letter, or take the form of a

voluminous document with appendices, plans and schedules. But in either case, its legal

effect is the same. A tender may contain a provision as to the time for which it is open for

acceptance, and provided the agreement not to revoke it before that time is otherwise

legally enforceable, it cannot be revoked before such stipulated time. If the tender is not

made irrevocable, it may be withdrawn at any time before acceptance. Sometimes, where

tenders are invited, there is a provision that tenders submitted are irrevocable until all

bids have been opened, and it is usual in contracts of any importance to require

tenderers to submit a bid bond, which may be forfeited if the tender is accepted and the

bidder fails to execute a formal contract. An owner who invites tenders is not, in the

absence of a binding agreement to that effect, obliged to accept the lowest, or any,

tender, or to reject a tender which may be irregular. This right may, however, be

restricted by a custom of the trade or be subject to an obligation to treat all bidders

fairly. Some difficulties appear to have resulted from the introduction into the bidding

process [by the Supreme Court in Ron Engineering] of the concept of two separate

contracts. viz. contract A and contract B, where contract B is the construction contract,

and contract A is a separate contract resulting from the invitation to bid -- which is the

offer -- and the submission of the tender in response thereto -- which is the acceptance.

If the invitation to bid contains specific terms and conditions, e.g. not to revoke the

tender for a specified period, such conditions will form part of contract A, and can be

enforced in the same way as any other contractual obligations. Insofar as contract B is

concerned, however, the tender is still only an offer which may or may not be accepted

by the owner. Contract A is not an agreement to enter into contract B, and unless and

until the tender is accepted by the owner, no contract B will ever come into existence.

Whether, in any given situation, a contract A ever comes into existence necessarily

depends on the particular facts of each individual case. If it does, it is difficult to see on

what basis an express term of the contract, e.g. a provision in the invitation to bid that

the owner is not obliged to accept the lowest or any tender, can be displaced by an

implied term or by a custom of the trade to the contrary.

12

In Ron Engineering, Justice Estey characterized the tendering process with which

the courts dealt in that case as a preliminary or initial contract leading to the formation of

a final contract. He referred to the initial contract as contract A to distinguish it from the

construction contract itself, contract B, which would arise on the acceptance of a tender.

He characterized contract A as being a unilateral contract which arose by the filing of a

tender in response to the tender call in that case. An appreciation of the incident giving

rise to the formation of contract A, and of the timing of that event, is essential. The

Supreme Court determined this based on the revocability of the bidder's offer.

13

At p. 272 [D.L.R.]:

The revocability of the offer must, in my view, be determined in accordance with the

"General Conditions" and "Information for Tenderers" and the related documents upon

which the tender was submitted. There is no question when one reviews the terms and

conditions under which the tender was made that a contract arose upon the submission

of a tender between the contractor and the owner whereby the tenderer could not

withdraw the tender for a period of 60 days after the date of the opening of the tenders

... Other terms and conditions of this unilateral contract which arose by the filing of a

tender in response to the call therefor under the aforementioned terms and conditions,

included the right to recover the tender deposit 60 days after the opening of tenders if

the tender was not accepted by the owner. This contract is brought into being

automatically upon the submission of a tender ...

.....

The tender submitted by the [contractor] brought contract A into life. This is sometimes

described in law as a unilateral contract ... Here the call for tenders created no obligation

in the [contractor] or in anyone else in or out of the construction world. When a member

of the construction industry responds to the call for tenders, as the [contractor] has done

here, that response takes the form of the submission of a tender, or a bid as it is

sometimes called. The significance of the bid in law is that it at once becomes irrevocable

if filed in conformity with the terms and conditions under which the call for tenders was

made and if such terms so provide ... complied with the terms and conditions of the call

for tenders. Consequently, contract A came into being. The principal term of contract A is

the irrevocability of the bid, and the corollary term is the obligation in both parties to

enter into a contract (contract B) upon the acceptance of the tender. Other terms include

the qualified obligations of the owner to accept the lowest tender, and the degree of this

obligation is controlled by the terms and conditions established in the call for tenders.

[Emphasis added.]

The Supreme Court stated the judicial objective of protecting the integrity of the bidding

system where under the law of contracts it is possible to do so. In so doing, it

represented the law of contracts. It recognized the existence of reciprocal obligations by

the owner in response to the irrevocable promise of the contractor. That does not

preclude the occurrence of a bidding process where a contract A does not arise. The

circumstances of each case must be examined to determine whether the invitation to

submit tenders is merely an invitation to treat or whether it is an offer to enter into a

preliminary contract: Canamerican Auto Lease, at p. 17.

14

Correspondingly, a tender, as an offer, unless specified to be irrevocable, may be

revoked at any time provided that it has not been accepted in the legal sense: Cheshire,

Fifoot and Furmston, Law of Contract, 12th ed. (1991), at pp. 46, 47. In the

circumstances that existed here, any of the bidders, as offerors, were at liberty to

withdraw their bids at any time before the Town communicated acceptance of a bid. In

Kawneer Co. v. Bank of Canada (1982), 40 O.R. (2d) 275 (C.A.); and in Ellis-Don

Construction Ltd. v. Canada (Minister of Public Works), (unreported, April 16, 1992, Fed.

T.D.) [reported 1 C.L.R. (2d) 193], bids were held on other bases to be offers in response

to invitations to treat that did not give rise to a preliminary contract.

15

In this analysis, I am not adopting the analysis in Megatech Contracting Ltd. v.

Ottawa-Carleton (Regional Municipality) (1989), 68 O.R. (2d) 503 (Ont. H.C.),

("Megatech"), at p. 507, which held that contract A arises only when the tender has been

accepted. The rationale of Ron Engineering is that contract A comes into being upon

submission of the irrevocable bid.

16

Arctic Co-operatives Ltd. v. Sigyamiut Ltd. (Receiver of), (unreported, April 2,

1991, N.W.T. S.C.) [reported 5 C.B.R. (3d) 271] dealt with a sale of land by a receiver.

With regard to the tender process, Justice de Weerdt noted, at pp. 10-13 [p.276 C.B.R.]:

It is trite law that a simple advertisement inviting the submission of tenders is not,

without more, anything other than an "invitation to treat" and does not, of itself alone,

constitute an offer the acceptance of which will create a legally binding contract: Spencer

v. Harding, [1870] L.R. 4 C.P. 561, [39 L.J.C.P. 332, 23 L.T. 237, 19 W.R. 48]; and see 9

Hals. (4th), para. 230; Chitty on Contracts 26th ed. vol. 1, para. 51; Cheshire, Fifoot &

Furmston's Law of Contract 11th ed., p. 45; and I.N.D. Wallace, Hudson's Building and

Engineering Contracts, 10th ed., p. 6. In the words of Bowen, L.J. in the memorable case

of Carlill v. Carbolic Smoke Ball Co., [1893] 1 Q.B. 256, [62 L.J.Q.B. 257, 67 L.J. 837,]

[1891-4] All E.R. Rep. 127 (C.A.) at p. 268 [Q.B.]:

... cases in which you offer to negotiate, or you issue advertisements that you have a

stock of books to sell, or houses to let, in which case there is no offer to be bound by any

contract. Such advertisements are offers to negotiate -- offers to receive offers -- offers

to chaffer, as, I think, some learned judge in one of the cases has said.

While the foregoing is all too familiar to counsel, I consider it worth setting down by way

of general legal background to better enable an understanding of the facts of the present

case and the law today as declared by the Supreme Court of Canada in Ron Engineering.

.....

It is of course apparent that the tendering process considered in Ron Engineering was

one which had evolved well beyond the rudimentary stage envisaged by Bowen, L.J. in

Carlill v. Carbolic Smoke Ball Co. and in Spencer v. Harding. As a result, the call for

tenders in that case being on terms and conditions contemplating an initial (but limited)

contract upon submission of a tender, that initial contract automatically arose when the

tender was duly submitted.

It was held in that case that in order for an initial unilateral contract A to arise, the

tender must comply with the "condition sale".

17

Northern Construction Co. v. Gloge Heating & Plumbing Ltd., [1986] 2 W.W.R. 649

(Alta. C.A.) addressed a construction sub-contract telephone bid situation. Irrevocability

of the bid was not specified, and yet a contractual obligation was found. In accordance

with usual practice, the mechanical subcontractor placed a last minute telephone tender

with the general contractor, and the general, in turn, relied upon this bid in placing its

irrevocable bid for the work. The general obtained the work and the subcontractor

declined to proceed. The Court held the subcontractor bound, following the principle of

Ron Engineering. That case is distinguishable and reconcilable. The basis of the

contractual obligation found to have existed between the subcontractor, Northern, and

the general, Gloge, was that the subcontractor knew that the general would select a

mechanical tender and rely upon it, and the subcontractor also knew that the tenders of

the general contractors to the owner would be irrevocable for the time set out in the

contract documents. The Court observed that those facts themselves might justify

holding the subcontractor bid to be irrevocable. In addition, the Court found at p. 9 that

expert evidence had demonstrated [at p. 653]:

... that it was normal and standard practice for general contractors to accept last minute

telephone tenders from subcontractors, and that it was understood and accepted by

those in the industry that while such tenders could be withdrawn prior to the close of

tendering, if not so withdrawn, such tenders must remain irrevocable for the same term

that the general contractors' tenders to the owner are irrevocable.

This industry practice is eminent common sense. Without such accepted practice the

tendering system would become unenforceable and meaningless.

Justice Irving then indicated that the subcontractor, Northern, could not withdraw its

tender upon application of the industry practice to that case.

18

Ron Engineering is the fountainhead for a stream of cases where a unilateral

contract A has been held to have arisen upon submission of an irrevocable bid: Calgary

(City) v. Northern Construction Co., [1987] 2 S.C.R. 757; Bate Equipment Ltd. v. EllisDon Ltd., (unreported, July 21, 1992, Alta. Q.B.) [reported 2 C.L.R. (2d) 157]; Slave

Lake (Town) v. Appleton Construction Ltd. (1987), 80 A.R. 276 (Q.B.); Protec

Installations Ltd. v. Aberdeen Construction Ltd. (1993), 6 C.L.R. (2d) 143 (B.C. S.C.);

Kencor Holdings Ltd. v. Saskatchewan, [1991] 6 W.W.R. 717 (Sask. Q.B.), ("Kencor

Holdings"); Scott Steel (Ottawa) Ltd. v. R.J. Nicol Construction (1975) Ltd., (unreported,

March 3, 1993, Ont. Div. Ct.); Martselos Services Ltd. v. Arctic College, (unreported, May

8, 1992, N.W.T. S.C.) [reported 5 B.L.R. (2d) 204]; A.W. MacPhail Ltd. v. Kelson (1989),

34 C.L.R. 1 (N.B. C.A.). Those cases consistently pursue the proposition of a preliminary

contract based on an irrevocable bid in accordance with tender conditions, and they are

all distinguishable from the facts of this case on that basis.

19

In determining that no contract A was formed, I have chosen not to follow the

reasons on this particular issue in Whistler Service Park Ltd. v. Whistler (Resort

Municipality) (1990), 50 M.P.L.R. 233 (B.C. S.C.), ("Whistler") which held that

irrevocability was not a prerequisite. Whistler involved a claim by a low bidder for a snow

removal contract. The contractor claimed that the municipality breached the terms of the

contract A formed after acceptance of the tender by changing the terms of the work. At

p. 30 [p. 247 M.P.L.R.]:

Upon consideration of the Ron Engineering case as a whole, my conclusion is that

irrevocability is not a prerequisite for the creation of a Contract "A". Rather, Contract "A"

comes into being upon the submission of the tender, and irrevocability, if present, is

merely a term of the tender documents which must be examined, as do all the terms, to

determine the nature of Contract "A", not the existence of it.

In my opinion, contract A rises upon the bidder incurring an obligation in accordance with

the contract terms. Here, under the terms of tender created by the Town, submission of

the bid by Murphy did not, in and of itself, create any obligation on the bidder Murphy. As

observed in M.S.K. Financial Services Ltd. v. Alberta (1987), 23 C.L.R. 172 (Alta. M.C.),

("M.S.K."), at p. 181:

Legal rights do not exist in a vacuum. A right of one person has a concomitant obligation

by another person. If there is no obligation by anyone there cannot be a right vested in

someone. Rights and obligations are the two sides of the same coin.

20

In my view, the creation of a contract A and of the obligations implied in Ron

Engineering are reconcilable with adherence to the common law of contracts. The

Supreme Court directed that the limits of judicial intervention for protection of the

integrity of the bidding system are:

... where under the law of contracts it is possible to do so.

21

In Ben Bruinsma & Sons Ltd. v. Chatham (City) (1984), 11 C.L.R. 37 (Ont. H.C.),

("Bruinsma"), at p. 50, this proposition was succinctly characterized:

When the plaintiff submitted its tender, the contract arose between the plaintiff and

Chatham whereby the plaintiff could not withdraw its tender and it became irrevocable

until the happening of the events referred to in ... the tender document ...

It is in that context in which Bruinsma held that a contract is brought into being

automatically upon the submission of a tender.

22

Murphy also relies upon Slave Lake (Town) v. Appleton Construction Ltd. (1987),

80 A.R. 276 (Q.B.), where a bidder attempted to change its bid after discovering an error

and the Court held that its bid was irrevocable. That case is distinguishable. It dealt with

construction of a waste water treatment system that involved sophisticated bidding

documents including, notably, a bid bond and language that contemplated the owner and

the successful bidder proceeding to a formal construction contract. At pp. 282-283, para.

45, the Court found that the facts of that case justified a finding of irrevocability and also

applied the industry practice. Justice Matheson noted there that it was the irrevocability

of the tenders after closing that is the premise upon which the modern authorities on the

subject now rest.

23

Murphy's bid was not irrevocable. Contract A did not arise. Therefore, there is no

basis for Murphy's claim for breach of contract.

Consequences of Contractual Obligations

24

In light of the proliferation of jurisprudence regarding tender situations that has

occurred since Ron Engineering, and because a substantial portion of the trial in this

action was devoted to the consequences of a contract A scenario, I have proceeded

onward to consider the other issues. If I am found wrong on the first issue, and it is

determined therefore that contract A was formed on the submission of Murphy's bid, then

I would have determined that:

25

Upon contract A coming into being:

a. there arises at law rights and obligations of the parties that are consistent with the

protection and promotion of the integrity of the bidding system where under the law of

contracts it is possible to do so.

b. the owner owes a general duty to treat all bidders fairly.

c. an owner has the right to include in the tender documents stipulations and restrictions

on the rights of bidders and to reserve privileges to the owner.

d. an owner does not have the right on consideration of competing bids to rely upon

undisclosed terms and conditions.

e. "Lowest or any tender not necessarily accepted" reserves conditionally to the owner

the privilege to decide not to proceed with the work at all, but does not allow the owner

to: (i) choose comparatively among the bidders based on criteria that has not been

disclosed to the bidders; or (ii) to award to another bidder or another person something

other than contract B.

f. general custom in bidding, and particular local customs, can result in implied

contractual rights.

g. an owner does not have the right to pass over properly filed bids and enter into

contract B with a bidder whose bid is informal, or invalid.

h. where there is a breach of contract A, the measure of damages can include: (i) the

cost of preparation of the bid; and (ii) upon the low bidder proving he would have

obtained the contract, the estimated loss of profit on the work.

Further Facts -- Contractual Obligations

26

Murphy resided outside the Town. O'Meara resided within the Town. I do not find

that the place of residence influenced the Town's decision.

27

Murphy had some experience in contracting summer construction work. As well, he

had plowed snow as a government employee for many years. This was his first real

involvement as a contractor in the snow plowing and snow removal business. He had

some basic equipment with which to carry out the contract. His equipment list indicated

that he would also buy a snow blower heavy enough for the streets; and he would rent a

grader if needed. Upon learning that he was the low bidder, he started looking for the

balance of the equipment required to do the work.

28

At the time of bidding, Murphy thought that the contract would be awarded based

on price. Based on past experience, he was generally aware that the Town would

consider equipment, price and capability. I interpret his understanding of this to have

been in the context of bidders having the basic qualifications to do the work, in light of

Murphy's expressed awareness of the contract para. 4 requiring adequate service.

29

Murphy estimated that his profit margin over the three-year term of the contract

would be 50%.

30

Les Hardy, now mayor of the Town, was in 1990 a councillor and chair of the street

committee. He had 17 years' experience on council. He testified that the Town was

dissatisfied with the service provided by Gordon Enterprises, especially in the previous

winter of 1989-90; and that the council was motivated by complaints from the Town

business association, whose main concern was that the contractor have adequate

equipment and manpower to perform the contract. The Town obtained legal advice to

enable council to require adequate service. The purpose of the privilege clause "lowest or

any tender not necessarily accepted" was never talked about within council, but was

understood to be to allow the Town the flexibility not to have to take the lowest of

highest tender. He was not aware of any custom in that regard.

31

When the bids were received, Mr. Hardy was surprised by the very presence of

Murphy's bid, because in his view Murphy did not have the equipment to do the work. He

indicated that the Town had no difficulty with Murphy's reputation as an operator.

32

Town council perceived that its privilege to choose among contractors, based on

the best interests of the Town, arose from the contract para. 4 that enabled the Town to

terminate the contract for inadequate service. According to Mr. Hardy, the reason that

Murphy did not obtain the contract was because he did not have sufficient equip ment to

do the work. Gordon was by-passed because council's previous experience was that he

did not do an adequate job.

33

On a canvass of earlier tender calls by the Town, over a period of 10 years, Mr.

Hardy acknowledged that historically the Town had awarded to the lowest bidder if the

bidder had, as applicable, the equipment or resources to do the job.

34

Councillor Miles Getson reiterated most of the evidence of Les Hardy. He mentioned

to Murphy, probably before the bids were submitted, that the contract would not

necessarily be awarded to the lowest bidder. In any event, Murphy proceeded on his own

expressed expectation that the award would go to the lowest bidder. Also, Getson did not

report this conversation to council.

35

Mr. Getson was a candid witness. On cross-examination, he acknowledged that the

Town was looking for the bigger contractors with the better equipment to bid the job;

that council expected the bids to come in at a higher price and was prepared to pay

more; and that council did not expect a bid from Murphy at all. Upon receiving the bids,

council did not want to take a chance on repeating the experience of poor quality service

of the previous three years. O'Meara had both the equipment and a proven track record.

Council wanted to award the contract to O'Meara, even though his bid was highest. It

appears that council evaluated the bids on a comparative basis. Mr. Getson reported at

trial that council considered that Murphy did not have the equipment to do the job. On

discovery, the following exchange occurred:

Q. ... are you saying that Mr. Murphy's equipment was believed to be sufficient; it's just

that O'Meara's was better? More sufficient?

A. More sufficient and more of it.

36

On cross-examination, Mr. Getson acknowledged that the Town did not stipulate

minimum equipment requirements to the bidders. He stated: "We didn't know we had to.

We know now." Upon being asked whether he thought the Town could choose whatever

bidder it wanted, he responded that that is why the Town chose the wording in the

advertisement. Council did not inform Murphy that his equipment was inadequate. On redirect, Mr. Getson testified that he believed that the Town had no duty to the bidders,

and stated:

The townspeople were the people we had to represent.

37

Three contractors, Roy Ramsay, Gerard Gallant and Leonard O'Meara, testified

regarding equipment availability, equipment required to do the work, and profit margins

on snow plowing and snow removal.

38

On considering all of the evidence, I find that the Town has not proven that Murphy

was not qualified to perform the contract. Certainly, it is understandable that the Town

would have preferred to have the service performed by O'Meara with his more complete

and sophisticated equipment. The equipment proffered by Murphy was somewhat

antiquated and undoubtedly would have performed a lesser job than O'Meara's

equipment. The Town was genuinely concerned over the potential for loss of service

during an equipment breakdown. However, Murphy did have basic equipment, and he

also a plan to obtain the balance of the equipment required to do the job. He was not a

"crank" bid without experience or financial capability. He had relevant business and snow

plowing experience and had the basic credentials to bid to become engaged in the snow

removal business.

39

Upon Murphy demonstrating the apparent minimum requirements of qualification,

in the absence of further specific standards in the tender documents, it was then

incumbent upon the Town to rebut, by showing that Murphy would not have had the

basic qualification to do the work. The evidence introduced by the Town has cast doubt

over the reliability and sufficiency of Murphy's existing and proposed equipment, but it

has not shown on the balance of probabilities that he was not qualified to do the work.

The proposed contract para. 4 is unhelpful, because it only operates in the event that

inadequate service is shown to have occurred during the term of the contract.

Reasons: Contractual Obligations

40

In Ron Engineering, the Supreme Court found an implied term of the contract that

imposed a qualified obligation on the owner to accept the lowest bidder. The degree of

that obligation is controlled by the terms and conditions established in the call for

tenders. The stated policy objective is protection of the integrity of the bidding process.

While Ron Engineering dealt with the obligations of a contractor to an owner, the principle

has been applied in subsequent cases to enforce the proposition that it is imperative that

the lowest qualified bidder succeed, especially in the public sector. The rationale is that

otherwise bidders doomed in advance by secret standards will waste large sums of

money preparing futile bids, and they will ultimately avoid participating in the bidding

process. This will result in the end objective of the system being denied, and lead to

financial loss for the public. Where, and to the extent that, a requirement of fairness

exists, it is there for the benefit of all participants in the tender process. The bounds of

the duty of fairness of the owner to all bidders has been the subject of much litigation.

41

The obligation to treat all bidders fairly was interpreted broadly in Chinook

Aggregates Ltd. v. Abbotsford Municipal District (1989), 40 B.C.L.R. (2d) 345 (C.A.),

("Chinook Aggregates"). There, the municipality invited bids on a gravel crushing

contract. The advertisement and instructions contained a privilege clause stipulating that

the lowest or any tender would not necessarily be accepted. The municipality had an

undisclosed policy of preferring local contractors whose bids were within 10% of the

lowest bid. The plaintiff, as low bidder, was bypassed. It was held that the municipality

breached an implied term of the contract, which came into existence upon submission of

the bid. The finding of this obligation was based on evidence of industry custom that the

lowest qualified bidder was entitled to acceptance. The trial judge held that the contract

privilege clause must be interpreted and qualified in light of that implied term. The Court

of Appeal affirmed the owner's duty to treat all bidders fairly and not to give any of them

an unfair advantage over the others.

42

No such local custom was conclusively established in this case. On that basis,

Chinook Aggregates is distinguishable. In any event, though, the following passage, at p.

349, regarding undisclosed conditions applies:

But where [the owner] attaches a condition to its offer, as the [owner] did in the case at

bar, and that condition is unknown to the [bidder], the [owner] cannot successfully

contend that the privilege clause made clear to the respondent bidder that it had entered

into a contract on the express terms of the wording of that clause... It would be

inequitable to allow the [owner] to take the position that the privilege clause governed

when the [owner] had reserved to itself the right to prefer a local contractor whose bid

was within 10 per cent of the lowest bid. By adopting a policy of preferring local

contractors whose bids were within 10 per cent of the lowest bid, the [owner] in effect

incorporated an implied term without notice of that implied term to all bidders including

the respondent. In so doing, it was in breach of a duty to treat all bidders fairly and not

to give any of them an unfair advantage over the others.

And at p.351:

... it is inherent in the tendering process that the owner is inviting bidders to put in their

lowest bid and that the bidders will respond accordingly. If the owner attaches an

undisclosed term that is inconsistent with that tendering process, a term that the lowest

qualified bid will be accepted should be implied in order to give effect to that process.

[Emphasis added.]

43

In Best Cleaners & Contractors Ltd. v. Canada (1985), 58 N.R. 295 (Fed. C.A.), at

p. 299, ("Best Cleaners"), the majority decision addressed the meaning of the standard

privilege clause:

The [owner's] obligation under Contract A was not to award a contract except in

accordance with the terms of the tender call. The stipulation that the lowest or any

tender need not be accepted does not alter that. The [owner] might award no contract at

all or it might award Contract B to Tower, [the competing bidder, who was arguably the

low bidder for the tendered work], but it was under a contractual obligation to the

[plaintiff bidder] not to award Tower something other than Contract B.

44

In a dissenting judgment, Justice Pratte recognized and defined the implied terms

regarding fairness, at p. 306:

... they simply impose on the owner calling the tenders the obligation to treat all bidders

fairly and not to give any of them an unfair advantage over the others.

45

The general duty of fairness is also discussed in Martselos Services Ltd.; Whistler,

at p. 33; and Bruinsma, at pp.50 ff.

46

In Kencor Holdings, the Government invited tenders for construction of a bridge.

The contract document stipulated that the Minister might refuse to accept, or accept, any

tender that the Minister considered to be in the best interests of the province. The

Government awarded the contract to a contractor that was represented locally, despite

the fact the plaintiff, a better qualified out-of-province contractor, was the lowest bidder.

This was held to constitute a breach of duty to treat all bidders fairly and to not give any

an unfair advantage. That duty was found to be an implied term of the contract which

resulted upon submission of the plaintiff's bid in response to the Government's invitation

to tender.

47

The Town says that for it to have been obliged to accept the lowest qualified

tender, there would have to have been in existence a custom or usage to that effect. The

Town relies on Hawes v. Sherwood-Parkdale Metro Junior Hockey Club Inc. (1991), 96

Nfld. & P.E.I.R. 169 (P.E.I. C.A.), at p. 172, where Chief Justice MacDonald adopted the

following statement from Georgia Construction Co. v. Pacific Great Eastern Railway,

[1929] S.C.R. 630, at p. 633, for direction as to when custom and usage can affect a

written contract:

Usage, of course, where it is established, may annex an unexpressed incident to a written

contract; but it must be reasonably certain and so notorious and so generally acquiesced

in that it may be presumed to form an ingredient of the contract.

The question for the trial judge is whether there is evidence to satisfy him judicially that

the alleged usage is so all persuading and so reasonable and so well known that

everybody doing business in that field must be assumed to know it and to contract

subject to it.

48

The Town submits that there was here no such custom or usage, or even if there

was, it cannot, as a matter of law, override the clear terms of the contract: Cartwright &

Crickmore Ltd. v. MacInnes, [1931] S.C.R. 425. In Acme Building & Construction Ltd. v.

Newcastle (Town) (1992), 2 C.L.R. (2d) 308 (Ont. C.A.) ("Acme"), affirming (1990), 38

C.L.R. 56 (Ont. Dist. Ct.), leave to appeal to S.C.C. refused (1993), 151 N.R. 394 (note)

(S.C.C.) it was held [at p. 309]:

In our opinion, even if there was acceptable evidence of custom and usage known to all

the tendering parties, it could not prevail over the express language of the tender

documents which constituted an irrevocable bid ...

With respect to accepting any given bid, the instructions to tenderers stated that the

"[o]wner shall have the right not to accept lowest or any other tender". This gave the

respondent the right to reject the lowest bid and accept another qualifying bid without

giving any reasons.

49

In Elgin Construction Co. v. Russell (Township) (1987), 24 C.L.R. 253 (Ont. H.C.),

("Elgin"), at p. 257, custom was reconciled with contract language as follows:

It is my opinion that no "custom of the trade" can be deemed to qualify the most explicit

words of the advertisement that "Tenders are subject to a formal contract being prepared

and executed. The township reserves the right to reject any and all tenders and the

lowest or any tender will not necessarily be accepted," and the equally explicit words in

the "Information for Tenderers", as stated in para. 12, "The Corporation reserves the

right to reject any or all tenders ... without stating the reasons and the lowest or any

tender will not necessarily be accepted."

Any "custom of the trade," as hitherto defined, is extirpated in its efficacy in the

contractual relations of the parties by the explicit words in the advertisement and

"Information to Tenderers," to which I have referred, which form a legal context in which

the plaintiff's tender was submitted. As a matter of law, that context precludes the

operability of such "custom". To deny this would be to destroy the doctrine that

contractual relations between parties are based on their objective manifestations of intent

to exchange binding promises. [Emphasis added.]

50

Power Agencies Co. v. Newfoundland Hospital & Nursing Home Assn. (1991), 90

Nfld. & P.E.I.R. 64 (Nfld. T.D.) went some distance toward reconciling Chinook

Aggregates and Best Cleaners with Acme, Megatech, Elgin and M.S.K., as follows [at

p.69]:

I do not interpret either Chinook Aggregates ... or Best Cleaners ... as going as far as to

say there is, at least in the face of an express term that the lowest of any tender need

not be accepted, an obligation on the owner to award a contract if there is a bid

complying with the terms and conditions of the call. Indeed Mahoney, J.A., as noted

above, confirmed the owner's right not to award a contract. These cases do illustrate the

courts using the implied term that all bidders be treated fairly to protect the integrity of

the system by ensuring that if contracts are to be awarded on anything other than

commonly accepted basis this must be revealed to bidders and that what is awarded is

what was called. In this case all bidders were aware of the terms and conditions set out

in the call for tenders and that the provincial preference legislation would be applied to

assess the tenders submitted.

I am persuaded that the clearly expressed term "The lowest or any tender will not

necessarily be accepted" means there is no obligation on the defendant under the law of

contract to award a contract, even if the first plaintiff meets all the requirements set out

in the tender call. [Emphasis added.]

51

On the consideration of competing bids, it is my view that the courts should pursue

the policy objective stated by the Supreme Court in Ron Engineering: to protect the

integrity of the bidding system where under the laws of contracts it is possible to do so. A

balanced approach of promoting this objective while adhering to established principles of

contract law is to recognize that: 1) the parties are at liberty to contract on whatever

terms that they choose; 2) to the extent that an owner wishes to reserve privileges, he

must do so in clear terms; and 3) an owner is not entitled to rely upon secret or

undisclosed preferences, or to proceed arbitrarily, and thereby choose from among the

bidders.

52

The new jurisprudence respects the law of contracts. It merely gives fuller

recognition to the practical requirement of fairness within the tender process.

Traditionally, contracts have been viewed not as isolated acts, but rather as incidents in

the conduct of a particular business. Contracts have been frequently set against a

background of common usage which may be supposed to govern the language of a

particular agreement. Custom comes not to destroy, but to fulfil the law. (See Cheshire &

Fifoot, at pp.123, 133). Prior to Ron Engineering, the courts gave effect to some limits on

the conduct of owners within the tender process through fraudulent misrepresentation:

If, however, it can be shown that the employer has no intention of letting the contract to

the person invited to tender, or to one of a number so invited, the invitation is clearly

fraudulent and an action will, it is submitted, lie to recover such expenses by way of

damages. [Richardson v. Silvester (1873) L.R. 9 Q.B. 34]: (as reported in Hudson's

Building and Engineering Contracts, 10th ed. (1970), at pp.229-230).

53

That appears to have been the basis of the approach taken most recently by in

Zutphen Bros. Construction Ltd. v. Nova Scotia (Attorney General), (unreported,

September 15, 1993 N.S. S.C.) [reported 12 C.L.R. (2d) 111], ("Zutphen Bros.").

54

In this case, the evidence of five witnesses, including two Town councillors and

three other snow removal contractors, discloses that there was not in existence an

established custom or usage as asserted by Murphy. Their evidence does indicate a

general common knowledge within those involved in tendering for services, regarding the

presence of this standard privilege clause, that such clause is generally followed by

awarding to the low bidder, and that such clauses should be followed.

55

The evidence of two of the three expert witnesses -- James Johnston, P.Eng., and

Laurie Coles, M.R.A.I.C., P.Eng. -- confirms a general construction and commercial

practice in this province that in a public tender situation, where there is no

prequalification, this privilege clause does not entitle an owner to arbitrarily reject the

qualified low bid and accept another. The opinion of the expert Wallace MacDonald,

P.Eng., is that this privilege clause gives the owner the right to select any bidder based

on the owner's best judgment. Mr. MacDonald acknowledged that in the absence of other

criteria the award should go to the low bidder; and he testified that the courts are driving

the construction industry toward this view. He qualified his opinion by noting that in

tender scanarios where the bidders are invited or prequalified, industry custom is that the

lowest bidder will be accepted. Mr. MacDonald observed that in this instance the Town's

tendering process was very informal and he questioned whether it should even be

considered in terms of customary practice in the construction industry. Mr. MacDonald

suggested that a better parallel for this case might be an individual soliciting prices on a

home and not accepting the lowest quotation. Mr. Coles observed on cross-examination

that there is an evolving custom at the interface of the law and the engineering

profession; and that engineers have been left to interpret.

56

In Tercon Contractors Ltd. v. British Columbia, (unreported, April 8, 1993, B.C.

S.C.) [reported 9 C.L.R. (2d) 197], ("Tercon"), at p. 24, it was held that where an owner

proceeds with the work, this standard privilege clause only entitles the owner to reject a

tender if the bidder is not qualified. In Tercon, the Minister had an undisclosed preference

for a certain kind of culvert, and bypassed the low bidder in order to obtain that

preference. The Court held that this bias constituted a secret preference that violated the

requirement of fairness. With regard to undisclosed conditions, Tercon stated at pp.31,

32 [p. 209 C.L.R.]:

There is nothing objectionable with preferences so long as they are disclosed.

57

The Town submits that it could not have made any clearer the extent to which it

intended to qualify its obligation to enter contract B. I do not accept that contention. In

my view, presence of the privilege clause "lowest or any tender not necessarily accepted"

in the invitation for tenders does not reserve to the owner the absolute right to choose

among the bids on a comparative basis. The limited purpose of that provision is well

expressed in Best Cleaners.

58

Murphy asserts that to allow the simple privilege clause used here to prevail, would

be to annihilate the objective of fairness directed by the Supreme Court in Ron

Engineering. I agree. In my view, the use of the boiler plate privilege clause alone, in the

words of the expert Johnston, allows the owner to decline to enter into a contract with

any of the bidders for good or bona fide reason, e.g., all tenders higher than the owner's

budget, intervening events resulting in the owner deciding not to proceed with the work,

or deciding to substantially change the work; or in the words of the expert witness Coles,

allows the owner to reject an unqualified bidder. It does not entitle the owner to

arbitrarily reject the low qualified bid and award the work to a higher bidder based on

terms or criteria undisclosed in the invitation or bid documents; and it does not allow the

owner to arbitrarily and without giving a reason reject all bidders. To obtain this

conclusion, I have necessarily departed from the view expressed on this issue in Acme,

and chosen to pursue the policy objective of fairness, within the law of contracts, stated

by the Supreme Court of Canada in Ron Engineering. (For further discussion on the

extent of the right of a public authority to abandon a procurement see Arrowsmith,

Government Procurement and Judicial Review, at p. 55.)

59

As the expert witness Coles advised, the owner must disclose to the industry in his

documentation all of the requirements he expects to have met. He cannot impose

something he has not indicated.

60

An owner can publish its invitation or prepare its contract documents so that a bid

does not give rise to contract A. Subject to public policy considerations, an owner can

include whatever terms he wishes in its contract documents in order to reserve the

privilege of determining and choosing a successful bidder on criteria other than price. An

owner can reserve the right to choose not to proceed at all with the work. Invitations and

bid documents can be designed and kept short and simple, or be made long and complex,

depending on the intended evaluation process and the scope of proposed work. In any

event, the principles of contract law, interpreted in the context of the fairness established

in Ron Engineering, prevail.

Informal Bids

61

Here, the O'Meara bid was not signed. Therefore, it was invalid, and had there been

a contract A with Murphy, the Town would have been obliged to reject the O'Meara bid as

informal. The expert evidence of Mr. Johnston confirms the existence of a custom in

commercial bidding in this province that unsigned bids are considered informal and, on

that basis, invalid.

62

Peddlesden Ltd. v. Liddel Construction Ltd. (1981), 128 D.L.R. (3d) 360 (B.C. S.C)

dealt with a subcontract on a construction project using a bid depository system. It was

held: (i) that the omission of a corporate seal from an accompanying bid bond was a

"mere slip" capable of subsequent correction that did not invalidate the contract; and (ii)

by comparison, failure to execute the bid bond at all would have rendered the tender

invalid since that was a required portion of the procedure in the bids depository system.

See also Ron Engineering, at p. 278, and Zutphen Bros., at p. 278 and regarding

"informal slips".

63

Here, the bidding process was informal. That is the owner's choice, and is quite

acceptable. In any event, the bidding process used by the Town in this case

contemplated that the bids would be in writing. The expert witness Johnston explained

that the purpose of this kind of requirement of properly completed bids is to avoid

scurrilous bids so that an owner can rely upon the bids. The concept of treating all

bidders fairly requires the owner to acknowledge informal bids to be invalid, and then to

operate fairly by considering only the bids that are properly submitted.

Damages

64

There is some apparent difference among the authorities regarding the measure of

damages flowing from a breach of contract A. That appears to occur because a breach by

the owner of contract A does not necessarily mean that the plaintiff would have been

entitled to obtain contract B. For instance, the owner could have rejected all of the bids:

M.S.K. Financial Services Ltd., at p. 180; Whistler, at pp. 26-27; and Chinook

Aggregates. There is authority for awarding the loss of profit: Martselos, at p. 13;

Kencor, at p. 721. Arrowsmith, at p. 325 [Government Procurement and Judicial Review

(Toronto: Carswell, 1988)], states:

Where a remedy is available for breach of an implied contract, a bidder will be able to

recover any profits he might have made but for the breach. Again, to recover any

damages he must prove he would have obtained the contract but for the breach. The

same principles will apply as regards causation ...

65

A court can draw an inference from the evidence that an owner would have

accepted the tender of the low bidder: Bruinsma, at p. 51. Loss of profit can be awarded,

notwithstanding that damages may be difficult to assess. Pitch, Damages for Breach of

Contract [Toronto: Carswell, 1989], p. 33, states [at p. 3-6, 2d ed. (1993)]:

... this loss of opportunity is properly compensable in a breach of contract action provided

the evidence establishes that there is some reasonable probability that the injured party

would have realized some substantial monetary value but for the breach of contract or

wrongful act. Often, proof of substantial damages may be impossible because the

calculation of damages, under the circumstances, is difficult and uncertain, but a

wrongdoer is not relieved from paying damages merely because they are difficult to

assess.

66

In this case, Murphy acknowledges that the cost of preparation of his bid was

nominal. He claims as damages his loss of anticipated profits over the term of the

contract. Had contract A arisen, then in my view the Town would have accepted Murphy's

bid as the low tender. The measure of damages would have been his estimated loss of

profit on the contract.

67

Murphy submitted a statement of projected earnings, showing a profit margin of

approximately 50%. This amounted to earnings per year of $11,000, $11,990 and

$12,900. In the trial, he acknowledged unaccounted expenses of approximately $2,000

per year. The Town's evidence showed that Murphy's projections were unrealistically low.

The witness, Ramsay, who is experienced in the highway snowplow business, reported his

experience of a profit margin of "10-15%, that fluctuates greatly".

68

Murphy's stated expenses do not include any wages and benefits for himself. The

Town's witness and current snow removal operator, O'Meara, actual experience over the

term of the contract was a break-even operation on revenues of $40,000. Mr. O'Meara's

expenses included wages for both himself and his wife. In 1993, Mr. O'Meara elected to

renew this contract for substantially the same price. It is difficult to construct a reliable

financial scenario, and the onus is on the plaintiff to show the loss of profit. However, it

does appear reasonable, after increasing Murphy's projected expenses to realistic levels

and considering the loss of opportunity for him to do his own work in his enterprise for a

basic wage, to conclude that a profit margin of approximately 15% is within the range of

reasonable projections. I therefore would have determined that the measure of damages

was the loss of profit of $4,800 per year. Interest would have been payable at the

prescribed rate, from the later of the date of notice of claim, being March 15, 1991, or,

on a proportionate basis, from the dates when instalments would have been received.

There was little real opportunity for mitigation of this loss.

Costs

69

As requested by both parties, I am prepared to hear from counsel before making an

order regarding costs.

70

The plaintiff's claim is therefore dismissed.

Action dismissed.

END OF DOCUMENT