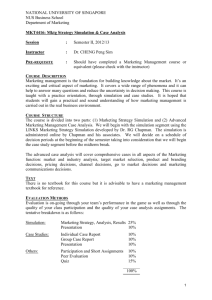

Analyzing Simulation Output

advertisement

Analyzing Simulation Output Q: When do we start analyzing simulation data? A: When we are satisfied that the simulation is running properly. Q: Are we satisfied with the retirement account simulation? A: Not really. Either our mean return is too high or the variance is too low or some simplification is getting in the way, but we aren’t getting enough of a chance of a negative return. Q: How do you know that? A: Primarily because the article I’m basing this on said that simulation shows that 2/3’s of the time the total is below the future value calculation (it helps to have outside information). To make our results more in line with the professional results, I have lowered the average return to 9%. Q: Besides that, are you satisfied the simulation is running properly? A: I have one more worry – doubts about the pseudo-random numbers generated by Excel. I haven’t bothered to do a statistical analysis of the results, but I‘ve noticed a couple of numbers pop up a bit too often for comfort. Part of the problem with random numbers is that truly random numbers could do that, so it’s hard to be sure when you have a problem with your pseudo-random numbers. We’ll just have to live with it. Q: How do we start analyzing simulation output? A: The first question is to consider is whether or not you can use all of your results. Q: Why shouldn’t we use all of our results for this simulation? A: Well, in this case you can, but it always the question to ask before you start analyzing your results. Q: What kind of simulation would have a problem with using all of its results? A: Any simulation that involves a waiting line. Q: Why is a waiting line a problem? A: A waiting line (or queue) is a problem because it starts out the simulation being empty. Q: What’s wrong with starting the simulation with an empty queue? A: If you are interested in measuring things like “time in line” or “number waiting” then starting with an empty queue might bias those measures. Q: What should we do about this? A: It depends on the simulation. If you are interested in watching the queue throughout the entire day (and you vary the simulated rate of customers arriving during the day) then you should use all your data, just analyze by time-of-day. If you are only interested in the queue during peak periods (more typical, nobody bother s to simulate slack times) then you have two ways to respond: throw out the earliest data (start-up period) or make the simulation so long that any start-up period effects are averaged out. Q: Which approach is better? A: Neither. The worry with throwing out data is that you are throwing out data, and you may throw out too little, or too much. The worry with averaging out the start-up effects is that you are never sure you have run the simulation long enough. Take your pick and start worrying. Q: Is that an issue for this simulation? A: No, we don’t have a waiting line. Q: Then where do we start analyzing this data? A: You begin by looking at the mean value of whatever numbers you wanted to know about – in this case, the total value of the retirement account at the end of 30 years. That number is shown in either cell E6 or E7. I used both of them just so you could see that there is difference between running a simulation 30 and 50 times. In general, the more repetitions of the simulation that you perform, the more certain you are that the results are acceptable (barring problems with validity and veracity). Q: What do you look for? A: For whatever the number tells you. Since we are comparing the simulated results to a calculated result, we compare the two values to see that they are fairly close to the same number. That is reasonable if our simulation is doing a good job, because the future value is an average calculation and running 50 simulations should give a pretty good average value. Q: Does that tell us the future value calculation is reliable? A: Not necessarily, there is more data to look at, such as the percentage of time that the simulated average is below the future value calculation. In the various spreadsheets I have looked at, that number has ranged from as low as 25% below to as high as 70% below. Further, I asked the simulation to tell me the percentage of the time that the simulated result was more than 10% below the future value result. That number has been very consistently around 20% and up. Finally, with all the data available to you, it would be a shame to not look at things like the maximum simulated return and the minimum, and to calculate a standard deviation for the total values of the retirement portfolio. The maximums are consistently in the $250K range, while the minimums seem to hover about the mid$140K’s. The standard deviations are in the mid- to low-$20K range. Q: Is there any other output we need to consider? A: Actually, there can be any other output you want. If you can think up a calculation that you would like to see for this data, all you have to do is ask the spreadsheet to show it and there it is. That is quite a bit easier than dealing with the partial information we get from most models. For right now, though, this is all I have asked for. Please note that you must ask the simulation for the calculation. It will not volunteer anything for you. If you don’t think of question, the simulation will not provide an answer. Q: So, what does all this tell us? A: As you have hopefully learned by now, that depends on you and your risk tolerance. You must decide whether the future value calculation is accurate enough for you or not. For the sake of argument, let’s say that it is not. You decide that the simulation has shown so much possible variation in the results, you are no longer satisfied with a simple point-estimate of the final value for your portfolio. You prefer the simulated results. Q: OK, so I prefer the simulated results. What do I do now? A: You look at the simulated results, average, minimum, maximum and standard deviation, and ask yourself if you are happy with the total value of your retirement account. Again, for the sake of continuing our discussion, let’s say that you are not happy with the total value. You would like it to be higher, a lot higher. Even the maximum value is unacceptable. Clearly, you have to change something. Q: What can I change? A: You can change anything in the simulation – any parameter you initially chose the value for, such as the mean return, the term, the payment amount, the down payment. You cannot change the structure of the simulation, such as using the normal distribution to simulate the market returns. So you need to think up the possibilities – what effect are you trying for, what changes can you make to create that effect, and what are the side effects of the changes you make. Then you start making each change and seeing how effective it is toward reaching the goal you have. When you find a group of changes that are more or less equally effective, compare them on the basis of their side effects to find the one that gives you the best result with the fewest unwelcome side effects. Q: How can you change the mean return? A: By changing your investment mix. Accepting a higher risk (greater standard deviation) you should be able to get a higher mean return. That does come with a greater likelihood of losing money, though, which might not be acceptable to you. All the changes have some bad points, though. A longer term means waiting longer to retire. A larger payment amount means having less money to spend now. A down payment might eat up your current savings, removing an important safety cushion for you. Which one you find most effective (best result for least pain) is up to you. Possibly it will be a combination of several changes that gives you the best result. Q: Will the computer help us figure out which is best? A: The computer is only a calculator. It will give you the result for any change you make. It will not suggest changes. The output you get might, if you are clever enough, point to further changes that will improve things in the direction you prefer, but there will be no flashing lights drawing your attention to the data. You must see the pattern, you must understand what it is saying, you must figure out the changes to make and you must make sure the simulation is running correctly after each change. Q: What if I get to the end of all my changes and still don’t like the result? A: Do something radical. Q: You mean, blow up a building somewhere? A: That would probably take care of your retirement problems, but isn’t really what I had in mind. Assuming your simulation is accurate, then a failure to find a satisfactory result means either you are asking the wrong question or are expecting the wrong result. Q: How could I be asking the wrong question? A: You are asking how much money you will have to live on when you retire. Maybe you won’t retire. If you are not planning to retire, you no longer need to save so much money, so maybe you need to change how you plan to spend the next few decades. Maybe you should be asking how much you can spend each year, or how long you need to save to accomplish some special goal. Q: How could I be expecting the wrong result? A: The result you are looking for is a reasonable date of retirement given your current financial condition (job, pay, expenses, etc). Maybe you need to change jobs, or work a second job, or work overtime, or drastically cut expenses (smaller home, cheaper car). Nobody likes these ideas, but the simulation is telling you that you cannot meet your goal with anything that you can reasonably do. So, think broadly. Q: Is this how simulation works in the business world? A: For a Monte Carlo simulation, yes. You start with something you need to know but don’t (rate of return on investments over a 30-year period), so you build a simulation that will tryout different values for that number and make calculations based on the different values that are simulated. You look at the results. You make changes. Either you find an acceptable solution, or you have to get creative. Q: You began by warning us about all the pitfalls that go with simulation, but do you really think that simulation is all that bad? A: Simulation always scares me, because I have almost thirty years experience in programming computers and I am fully aware of how many simple errors I have made that dramatically changed my results. Keep in mind that that doesn’t include all the mistakes I never caught. Simulation requires almost a paranoid state-of-mind. You must constantly be looking for something that might be wrong, and checking it. Even with this simple little simulation, I’ve gone over and over the formulae and output to see if I have made any mistakes. Most people don’t have the patience to do that. Simulation is a seductively powerful tool, because it can represent almost any situation and give you almost any data you ask for. It is easy to miss the fact that it will still give you data when you have made a mistake in setting up the simulation. Too many simulators are overly confident that they haven’t made any mistakes or, if they have, “the computer will make up for them.” It won’t. It will leave you hanging out on a limb when your brilliant ideas fail to work, because the simulation is incorrectly set up. I am not saying you shouldn’t use simulation. I am asking you to be very careful.