Getting Started: The Cruise Ship Analogy

advertisement

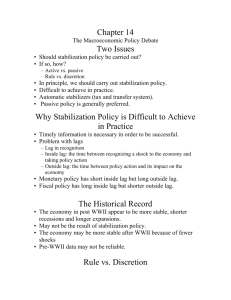

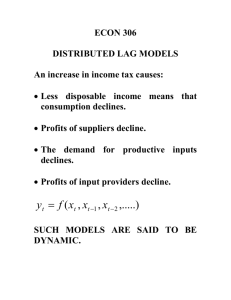

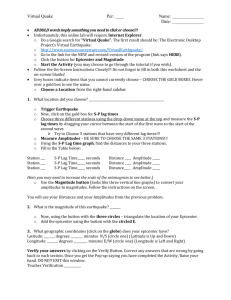

Getting Started: The Cruise Ship Analogy Use the space below to draw a cruise ship that represents the US economy. Key Terms from cruise ship example: 1. Fiscal policy (FP) 2. Monetary policy (MP) 3. Recognition lag 4. Implementation lag 5. Effectiveness lag 6. NAIRU 7. Full employment 8. Open market operations 9. Potential growth rate of economy 10. Stagflation 11. The FOMC 12. Exogenous shocks 13. Overheating 14. Speed limit of the economy The Cruise Ship Goals (the port) 1. Stable Prices 2. Full Employment (NAIRU) 3. Economic Growth (PGE) NAIRU (Non Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment) – the lowest the unemployment rate can go without inflation accelerating. We really don’t know exactly what this number is and it probably changes through time. Most economists would agree that NAIRU is somewhere around 5%, although this number is more uncertain given the Great Recession of 1997 – 1999. PGE (The Potential Growth rate of the Economy) – The fastest real GDP can grow without inflation accelerating. This growth rate is often referred to as the speed limit of the economy or the sweet spot of economic growth. Similar to NAIRU, PGE is a concept and we are not really sure what number to use and thus, we often talk about NAIRU and PGE in ranges. I would think that most economists put PGE between 2.5 and 3.5%. Any growth above that would be inflationary with the implication of overheating.1 Policy Lags 1. Recognition lag: The recognition lag is the time it takes policy makers to identify the current level of economic activity as well as where the economy is headed. We would think it would be easy to know current economic conditions given the constant stream of economic data available, but this is not necessarily the case since much of this data is reflecting previous economic activity. For a case in point of the recognition lag consider the following: At an FOMC meeting in October of 1990, Chairman Alan Greenspan did not recognize the economy was in the midst of an “official recession,” a recession that is commonly referred to as the gulf war recession.2 Lags are so important for policy makers and we assume that the recognition lag is the same for Fiscal policy makers (FP) as it is for Monetary policy makers (MP). That is, we assume that the economists that work on the council of economic advisors to the President and the economists that work for the Federal Reserve are equal in their abilities to recognize where the economy is and where it is headed. Overheating is a common ‘economic’ term and is associated with aggregate demand outstripping aggregate supply. 2 The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) is the official recession dating body and they typically identify recessions well after they are over. For example, the trough (end of) the 2001 recession occurred in November 2001 but wasn’t announced by the NBER until July 17, 2003! Chairman Bernanke used to be a member of this committee. For all the official recession dates, as well as more information about the process, go to http://www.nber.org/cycles/cyclesmain.html. 1 2. Implementation lag: The implementation lag represents the time lag between recognizing a need for discretionary policy and the time it takes to implement the policy (i.e., how long it takes the fiscal authorities to turn the wheel. For Fiscal policy, this lag can be quite long since our elected officials have to write up the policy and then talk about the details. As we all know, the political process, say, for a recommended tax cut can become very tedious and take many months of discussion in the House of Representatives and/or US Senate. For Monetary policy the implementation lag is very short, as the FOMC directs the federal funds desk to change the target for the federal funds rate by conducting open market operations. According to a high ranking Federal Reserve official, open market operations take about 15 seconds to perform! 3. Effectiveness Lag: The effectiveness lag refers to the time it takes for the implemented policy to influence real economic activity. In term of the cruise ship example, it represents the time it takes for the cruise ship to turn once the wheel is turned (i.e., once the policy is implemented). For Fiscal policy, the effectiveness lag is thought to be relatively short. For example, once a tax cut becomes effective, households immediately have more disposable income and chance are good, they will spend it and thus, economic activity will rise quite quickly. For Monetary policy, the effectiveness lag is long and variable, with the typical range of time being anywhere from 6 months to 2 years.3 Some economists believe that the effectiveness lag for monetary policy can be even longer than two years.4 This lag in monetary policy means that the Federal Reserve must be forward looking and thus, the “Fed” spends a lot of its resources in building and analyzing economic forecasting models. 3 This range is associated with the following reference: Milton Friedman and Anna Jacobson Schwartz, A Monetary History of the United States, 1867-1960. Princeton: Princeton University Press (for the National Bureau of Economic Research), 1963. xxiv + 860 pp. 4 When I spoke with Frederic Mishkin during his visit to Penn State, he suggested that the lag between changes in Federal Reserve policy and its impact on inflation is “at least two years.” This fact must be kept in mind since there is a group of economists adamant about inflation targeting, and thus, to successfully target inflation, you must be able to forecast inflation 2 plus years into the future, a difficult task indeed!