2 Removal of Quotas under the Agreement on Textiles and Clothing

advertisement

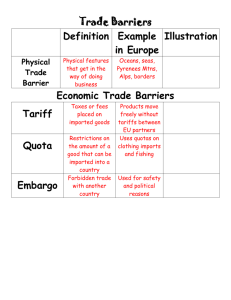

Implications of the Removal of Quotas in Textiles and Clothing Trade by Eckart Naumann* tralac Trade Brief No 8/2004 December 2004 * tralac Associate Abstract This trade brief provides an overview of key developments in the global textile and clothing trade regime in the context of the removal of quotas under the WTO Agreement on Textiles and Clothing. The views presented in this paper are those of the author alone and do not necessarily reflect those of tralac (Trade Law Centre for Southern Africa). Any errors are the author’s own. tralac (Trade Law Centre for Southern Africa) p.o.box 224, stellenbosch, 7599 south africa c.l.marais building, crozier street, stellenbosch (t) +27 21 883-2208 (f) +27 21 883-8292 (e) info@tralac.org © Copyright Trade Law Centre for Southern Africa 2004 Table of Contents 1 Textiles and the WTO: The Multifibre Agreement ____________________________ 1 2 Removal of Quotas under the Agreement on Textiles and Clothing ______________ 2 3 Global Textiles and Clothing Trade _______________________________________ 4 4 Some Implications of an End to Quotas____________________________________ 7 5 Reaction to the Removal of Quotas _______________________________________ 9 6 Summary of key Issues _______________________________________________ 11 www.tralac.org tralac Trade Brief No 8/2004 www.tralac.org 1 Textiles and the WTO: The Multifibre Agreement For more than three decades the textile and clothing sector has been the subject of special attention in the World Trade Organisation (WTO) and its trade in goods oriented predecessor, the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). This is partly because the textile and clothing sector – one of the most widely distributed industries in the world and a key provider of employment – has long been recognised as an essential factor for economic and social development and one where market interventions were deemed to be necessary. But since labour costs are an important differentiating component of this sector’s competitiveness, a number of industrialised countries (who might otherwise have been unable to compete) sought to shield this sector from foreign competition. This led to quantitative restrictions being introduced especially by Europe and the United States, on top of already high tariff-based restrictions. Although quantitative restrictions had been in place even before then, 1974 saw the inception of the Multifibre Agreement (MFA) which was a formalisation of quota restrictions in textiles and clothing trade. The MFA succeeded the Long-Term Agreement on International Trade in Cotton Textiles (LTA), which had been in effect since 1962. While the MFA was not specifically time-bound, it signalled the beginning of a long-term shift in the dynamics in the global textile and clothing sector. It was renewed in 1977 and again in 1981, 1986 and 1991. The MFA also signified a major departure from GATT principles, and could thus be classified as a derogation from GATT rules. In the context of the MFA, quotas were determined on an annual and differentiated basis. Quota-imposing countries set their own quantitative restrictions according to domestic economic policies and local industry dynamics. This meant that many countries remained entirely unconstrained by quotas (or faced restrictions in only a few certain categories), while others faced across-the-range restrictions. Quotas can in effect be seen as a tax levelled against the exporting country, with a 2001 study estimating that quotas on India’s exports were equal to an equivalent tax in 1999 of 40% and 19% for exports to the US and EU respectively. Despite the MFA, new growth in the textile and clothing sectors took place mainly in developing countries, attracted by lower overheads and even lower wage rates. But the MFA also had the important effect of being responsible for a much wider diffusion of the textile and particularly the clothing sector than would otherwise have been the case. Since quota restrictions forced producers to seek new and less quota-constrained 1 tralac Trade Brief No 8/2004 www.tralac.org locations, countries that would otherwise not have been the location of choice became important production centres. Examples include Bangladesh and Mauritius, whose producers compete mainly in otherwise constrained product categories. Quotas not only led to a far wider dispersion of investment and related employment opportunities, but also increased the real margin of preference that Europe and the US’ preferential trade partners enjoyed. Duty and quota-free market access thus took on far greater significance than would have been the case in an unrestricted market, where production would simply have gravitated towards lowest cost producing countries of the world. For example, under the Lomé Conventions (which later became the Cotonou Agreement), 77 ACP developing countries are able to access the EU market free of duty and quota restrictions for textile products. These preferences were a key driver in the development of the textile sector in Mauritius, having initially attracted investors from quota-constrained Asian countries. 2 Removal of Quotas under the Agreement on Textiles and Clothing While the initial objective of the MFA was to prevent the “uncontrolled” expansion of textile and clothing exports from developing countries, it took over twenty years for an agreement to be concluded that would see the eventual removal of these quota restrictions. While the textile and clothing sector had for a long time enjoyed a special dispensation within the multilateral trade regime including the Uruguay round of trade negotiations, the WTO Agreement on Textiles and Clothing (ATC) eventually became the instrument that was to regulate quota phase-out. It was implemented in 1995, and set specific targets over a 10-year period ending with the final tranche of quotas being removed on 1 January 2005. The ATC is binding on all WTO member States. At the first stage of quota phase-out, lasting from 1995 to 1997, 16% of developed countries’ imports were freed from quota restrictions, with each subsequent period seeing a larger proportion of quota being removed. However, since the quota removal is heavily back-weighted (i.e. the largest proportion of imports – namely 49% - is to have quotas removed only by 01 January 2005), the effective liberalisation of quotas will occur mainly at the end of the 10-year period. Quota-removal percentages are based on a country’s total textile and clothing trade in 1990, rather than trade in categories that were quota-constrained. A quota is defined to be constraining when quota utilisation levels are at least 85% (this being the US interpretation) and 95% (EU interpretation). Countries would therefore have been induced to initially remove quotas in categories where competing imports were not so much of a threat, for example instances where actual imports were already well below quota limits. A study has shown that in 2001 (still 2 tralac Trade Brief No 8/2004 www.tralac.org part of Phase 2 of the quota removal process) well over 50% of Asian countries’ aggregate textile and clothing exports to the US were still constrained by quotas. Not only does the ATC set predefined quota removal targets, but also provides for an increase in the remaining quota levels in the intervening years. In other words, existing quota levels must not only increase in accordance with a certain percentage, but the rate of expansion should also increase at each stage. The ATC also requires every stage of quota removal to include goods from all four of the pre-defined categories, namely “tops and yarns”, “fabrics”, “made-up textile products” and “clothing”. The table below shows the general schedule for quota removal and quota growth rates. Table 1 Quota removal under the ATC Stage of quota removal Percentage of products to be brought under GATT (including removal of any quotas) Annual increase in remaining quota growth rates (%) Stage 1: 1 Jan 1995 to 31 Dec 1997 16% (minimum, taking 1990 imports as base) 16% Stage 2: 1 Jan 1998 to 31 Dec 2001 17% 25% Stage 3: 1 Jan 2002 to 31 Dec 2004 18% 27% Stage 4: 1 Jan 2005 49% (maximum) No quotas left Full integration into GATT (and final elimination of quotas, termination of ATC) The actual formula for import growth under quotas is: by 0.1 x pre-1995 growth rate in the first stage; 0.25 x Stage 1 growth rate in the second stage; and 0.27 x Stage 2 growth rate in the third stage. 3 tralac Trade Brief No 8/2004 www.tralac.org 3 Global Textiles and Clothing Trade Global export data covering the past four decades reveals that developing countries’ share of textile and clothing exports has been growing rapidly, while that of industrialised countries has been in decline. In the late 1980’s, developed countries’ underlying fears were probably realised when their share of global textile and clothing exports was overtaken by that of developing countries. A decade later, developing countries were responsible for over half of global textile and nearly three-quarters of global clothing exports, up from a less than 20% aggregate in the early 1960s. In 2001, the last year for which complete cross-sectional data was available at the time of writing, China was a clear leader in terms of aggregate textile and clothing exports. Its share of world clothing exports in that year equates to almost 20% of the world total, rising to 31% if one includes Hong Kong’s contribution. In textiles, China’s share of the world export market is 11%, rising to 20% with Hong Kong. China has in recent years become the new super-power among textile and clothing producers, and probably the largest threat facing the existence of textile and clothing production in competing countries. Not surprisingly, the country has also been the subject of the largest number of quota restraints. To place this into context, China in 2001 faced export quotas on almost 60% of its textile and clothing exports to the US, compared with 53% for Asia overall, 13% for Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) under AGOA and 0.5% for NAFTA countries. As the following table indicates, the world’s leading clothing exporters – with few exceptions – are located in Asia. Many of these have shown significant export growth over the past decade, with notable increases recorded not only by China, but also by Mexico, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Morocco. Significantly, no countries from the SSA region are among even the top 20 clothing exporting countries. The situation is similar among the leading textile exporters, with China holding the top position. Other major suppliers to the world market are located predominantly in South Asia, including India, Pakistan and Indonesia. 4 tralac Trade Brief No 8/2004 www.tralac.org Table 2 Top 10 Exporters of Clothing and Textiles in 2001 (excluding EU, US and Canada) Rank Clothing WORLD total 1990 2001a US$ mn. US$ mn. 108,130 193,690 9,669 36,650 15,406 Textiles WORLD total 1990 2001a US$ mn. US$ mn. 104,350 146,980 China * 7,219 16,826 23,446 Hong Kong, China 8,213 12,214 587 8,011 Korea, Republic of 6,076 10,941 1 China * 2 Hong Kong, China 3 Mexico * 4 Turkey 3,331 6,661 Taipei, Chinese 6,128 9,904 5 India 2,530 5,483 Japan 5,859 6,198 6 Indonesia 1,646 4,531 India 2,180 5,375 7 Korea, Republic of 7,879 4,306 Pakistan 2,663 4,525 8 Bangladesh 643 4,261 Turkey 1,440 3,943 9 Thailand 2,817 3,575 Indonesia 1,241 3,202 10 Romania 363 2,780 Mexico * 713 2,091 Source: WTO (2004c) based on various statistical databases Notes: * includes processing zones, ** includes Secretariat estimates, a data for 2001 was used as 2002 data was not available The real importance of textile and clothing exports to each country is indicated by contrasting the value of sectoral exports with total merchandise exports. While this ignores the sometimes significant contribution to GDP of the services sectors (for example, in the case of both India and Mauritius service exports are beginning to play an increasingly important role), it nonetheless provides a good indication of the relative importance that this sector plays in terms of general economic activity, employment, foreign exchange receipts and so forth. It also provides an indication of a country’s vulnerability or potential to benefit from the phasing out of textile and clothing quotas under the ATC. Countries with a high correlation between direct quota restraints and exports volumes are likely to benefit the most from quota removal, at least in absolute terms. 5 tralac Trade Brief No 8/2004 www.tralac.org While WTO estimates show that textile and clothing exports on average account for 2.4% and 3.2% of total merchandise exports respectively, large intra-country variation exists. The following table quantifies this by listing the twenty countries having the highest proportions of “export reliance” on this sector. Cambodia, Macao (China) and Bangladesh show the highest reliance on clothing exports, whereas Pakistan shows the highest reliance on textile exports. Ratios in the relatively more capital-intensive textile sector are lower than in clothing. Mauritius (clothing exports) is the sole African country featuring on the list. Under the MFA quota system and even under the current ATC, clothing exports have generally faced stricter constraints than textile exports. Table 3 Countries with largest ratio of clothing exports to total merchandise exports (excludes EU, US and Canada) Rank Clothing 2002 2002 Exports % Textiles US$ mn. 6 2002 2002 Exports % US$ mn. WORLD 200,850 3.2 1 Cambodia * * 1,125 (a) 81.7 2 Macao, China 1,648 3 Bangladesh 4 El Salvador * 5 Mauritius 6 Dominican Republic *,** 7 World 152,150 2.4 Pakistan 4,790 48.3 70.0 Nepal 165 (a) 22.4 4,131 67.8 Macao, China 326 13.8 1,841 61.5 Turkey 4,244 12.3 949 54.1 India (a) 12.1 2,712 (a) 50.9 Bangladesh 469 7.7 Sri Lanka 2,326 49.5 Taipei, Chinese 9,532 7.0 8 Tunisia 2,687 39.5 Egypt 290 (a) 7.0 9 Honduras 475 37.4 Korea, Republic of 10,586 6.5 5,375 10 Morocco * 2,413 30.4 China * 20,563 6.3 11 FYR Macedonia 319 (a) 27.7 Hong Kong, China 12,374 6.2 12 Romania 3,251 23.4 Latvia 131 5.7 tralac Trade Brief No 8/2004 www.tralac.org 13 Turkey 8,057 23.3 Indonesia 2,896 5.1 14 Pakistan 2,228 22.5 Belarus 407 5.0 15 Nepal 154 (a) 20.9 Sri Lanka 202 (a) 4.2 16 Bulgaria 1,066 18.6 Lithuania 227 4.1 17 Jordan 296 (a) 12.9 Slovenia 355 3.7 18 China * 41,302 12.7 Czech Republic * 1368 3.6 19 India 5,483 (a) 12.4 Tunisia 232 3.4 20 Hong Kong, China 22,343 11.1 Iran, Islamic Rep. ** (a) 2.8 674 Source: WTO (2004c) based on various statistical databases Notes: * includes processing zones, ** includes Secretariat estimates, a 2001 figure, as 2002 unavailable 4 Some Implications of an End to Quotas There is much divergence of opinion with regard to the likely implications of an end to quotas. But never before has a WTO agreement caught so much attention, as the finalstage of the ATC drew near. Since this last stage of quota removal will not only see the largest percentage of quotas being removed in absolute terms, but also the inclusion of most sensitive categories (which were held back earlier), there is little doubt that the lifting of quotas will have a significant and wide impact. Since quotas were in the past applied differentially according to source country and product line, there will very likely be winners and losers in the post-quota environment. Already the often-seen unity between developing countries has been undermined as 2004 year-end drew near, with some developing countries likely to emerge as clear beneficiaries, while others face major economic upheaval. Both proponents and opponents of textile quotas have become more vociferous of late, with growing calls for an extension of quotas resulting in an emergency meeting in the WTO’s Goods Council in October 2004. The pending removal of quotas is likely to have various dimensions. These include the political dimension, which relates to the credibility of WTO agreements, their binding status on member States, and the credibility of the multilateral rules-based trading system in general; the consumer perspective, which relates to the gains in welfare through lower prices that are likely to emanate from quota removal; the efficiency 7 tralac Trade Brief No 8/2004 www.tralac.org dimension, relating to market distortions brought about by artificial trade barriers (which distort production and inevitable world market prices), and the loss of benefits to producers and employees (who benefited from indirect protection either through an absence of quotas and / or through preferential trade agreements with industrialized countries). While it is difficult to make rigorous predictions, it is highly probable that there will be substantial consolidation in global textile and clothing production, and with it changes in the geographic location of producers. Some observers have predicted a substantial reduction in the number of countries that the major textile and clothing producers will buy from, and the emergence of bigger and stronger multinational buyers that are able to base their purchasing decisions on a new set of market forces. A study conducted in the US in 2003 found that leading US retailers predicted that they would “reduce by twothirds the number of countries they deal with at present in a post-quota era”. While there may well be a shift in production from industrialised countries (mainly the EU and US) to low-cost locations, the largest relative shifts are predicted to occur between developing countries as producers seek to consolidate in the lowest-cost locations. This increasing reliance and downward pressure on labour costs as a dominating factor for competitiveness is therefore sometimes referred to as a “race to the bottom”. A study that calculated levels of risk associated with quota removal (based on trends in US imports) found that current ‘preferential’ regions of supply – namely NAFTA, SSA (through AGOA) and the Caribbean Basin countries – were highly dependent (indirect) beneficiaries on the quota constraints faced by China and other Asian-based exporters. The following diagram shows that a large proportion of textile and clothing exports from NAFTA countries, SSA and the South American / Caribbean countries (under the CBI) took place in categories heavily constrained by quota restrictions in other parts of the world. NAFTA, SSA and CBI countries are thus likely to face significant increases in competition in the post-quota environment. In the diagram below, risk levels range from ‘low’ (product categories where the ATC has already eliminated quotas, or for which no constrained suppliers exist), to ‘high’ (associated with products for which producers in the given region are unconstrained by quotas, but producers in other regions face quota restraints). 8 tralac Trade Brief No 8/2004 www.tralac.org Fig. 1 Predictions of US apparel imports 2002-2005, by source and risk level (US$ mn. and percent) 100% 90% 80% 70% 60% 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% NAFTA SSA CBI ASIA CHINA 8,461 802 12,768 7,662 304 Medium 47 129 1,311 12,768 3,189 Low 876 21 1,049 3,997 2,749 High Source: Nathan Associates (2002), based on US Dept. of Commerce China and India are both expected to be major beneficiaries of quota removal, both with respect to the US and EU markets. There are numerous reasons for this, including current quota constraints, the size of each country’s domestic textile and clothing industries and installed capacity, and their attractiveness as a destination for investment resulting from a relatively low-cost and productive workforce (which is largely nonunionized and subject to few minimum working conditions). Various sources also claim that China’s direct and indirect export subsidies (in the form of low-cost loans to manufacturers and a currency pegged to the US dollar at artificial levels) are a major reason for that country’s substantial competitiveness. A recent WTO study forecasts Chinese textile and clothing exports to the US to surge 3-fold in terms of market share, and those from India record a 4-fold increase albeit off a lower base. The same report predicts the greatest losses to accrue to African countries and Mexico. One analysis shows that during Stage II of quota phase out China’s exports already doubled in 12 out of 18 categories. 5 Reaction to the Removal of Quotas With the pending threat of a major surge in Chinese textile and clothing exports to the US authorities there are already determining safeguard measures to protect their local industry. Upon China’s accession to the WTO in 2001, an agreement was also concluded that would provide US textile producers with the right to request relief in the form of safeguards until 2008. While China has lobbied hard for the last stage of quota removal to go ahead as scheduled, it has recently bowed to US and EU pressure and agreed to the imposition of a voluntary export tariff. Chinese authorities would levy this 9 tralac Trade Brief No 8/2004 www.tralac.org tariff on its own exports, and be based on volume rather than value ostensibly to encourage higher value-added manufacturing. As little is yet known about the level of the proposed tariff, it is unclear whether it will have a dampening effect on the expected surge in exports. Considering that China’s production costs are already only a mere fraction of those in the EU and US, it is unlikely that anything but a draconian tariff will do much to constrain its exports. During the months preceding quota removal frantic last-minute efforts were made by certain countries wanting to postpone the final implementation of the ATC. As could be expected, dissenting voices were heard mostly from stakeholders facing negative repercussions in a liberalised market. In some countries, for example the United States, manufacturer associations have been lobbying against quota removal or at least the imposition of transitional measures, while the retail sector (notably global branded goods companies who manufacture mainly in China) has vehemently opposed any postponement of quota removal or imposition of safeguard measures. But on the whole, efforts to postpone the phasing-out have not been driven only by the US and EU. Proponents of a postponement have emerged mainly from the ranks of affected developing countries (Mauritius, Bangladesh etc.) and manufacturers’ organisations both in Europe and the US (for example ATMI, the American Textile Manufacturers Institute). As is reflected in Table 3 earlier, the economies of Bangladesh and Mauritius are among the most highly dependent on textile and clothing exports. One initiative opposing the last stage of quota phase-out is the Istanbul Declaration, which was initially endorsed (in March 2004) by leading American and Turkish textile and clothing industry organisations. It has since been further supported by approximately 130 industry organisations from almost 50 countries including Bangladesh, Kenya, Lesotho, Mauritius, South Africa, Swaziland and Zambia. The declaration called for an urgent meeting of the WTO to examine whether the phase-out of quotas should be extended by three years to the end of 2007, or whether other remedial action should be taken. Opponents of a postponement of quota phase-out have been questioning the negative impact that such a move would have not only on their industries, but also the multilateral trading system in general and with it the credibility of the WTO. Their position is that any remedies should be in the form of structural adjustments within the sector as it moves towards greater competitiveness and away from a reliance on quotas. In this regard, they argue, assistance should be sought from institutions such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. At the same time, existing trade remedies available to 10 tralac Trade Brief No 8/2004 www.tralac.org WTO members are said to be sufficient instruments for dealing with any major structural problems following quota phase-out. Of course, previous dispute settlement and countervailing measures have in the past frequently been rendered ineffective by onerous pre-conditions and time lags. But, it should be noted that China’s accession to the WTO was subject to certain additional trade remedies should Chinese exports unduly threaten the industries of its trade partners. Under the accession agreement, for example, the US can limit Chinese export growth to an annual 7.5% per annum until 2008. 6 Summary of key Issues It is clear that there is no simple solution to the concerns expressed by stakeholders facing challenges relating to the removal of quotas. The ATC’s schedule for the removal of textile and clothing trade quotas has been largely adhered to over the past decade, and despite opposition from many quarters, its final stage is set to be implemented as scheduled. While it is impossible to accurately predict winners and losers of the changes happening to global textile and clothing trade, the summary below outlines some of the main results that can be expected while summing up the key issues. An awareness of the possible impacts of quota removal will allow both industry stakeholders and policy makers to respond appropriately to the challenges facing the sector. The impact of quota elimination under ATC rules can thus be broadly summarized as follows: Beneficiaries of the final stage removal of textile and clothing quotas are likely to be those countries currently facing high quota restrictions either in the US or EU markets, or both. But the lifting of current quota restrictions is unlikely to be sufficient to guarantee benefits in the post-quota environment; rather, international competitiveness in the absence of quotas is required. For this last reason countries like Bangladesh are likely to suffer, who despite preferential market access to the EU faced restrictions in the US market. Without quotas, global demand especially from large European and US retailers is likely to gravitate towards currently quota-restricted yet competitive countries. Main beneficiaries are likely to include China (incl. Hong Kong), India and Pakistan; 11 tralac Trade Brief No 8/2004 12 www.tralac.org Consumers in general are likely to be major beneficiaries, as the removal of market impediments should increase the competitiveness of the sector and drive down the price of textiles and finished garments; At the same time, employment in countries with higher labour costs is likely to decrease as firms lose orders in favour of more competitively priced suppliers, or as downward pressure on prices results in related downward pressure on wages; Investors in textile and clothing enterprises in certain developing countries not subject to restrictive quotas (i.e. those having benefited indirectly from quotas imposed on competing countries) may find that their investments are less sustainable when textile and clothing trade becomes based more on principles of free trade rather than market distortions; Manufacturers located in countries not benefiting from quota phase-out but with strong and established commercial ties with buyers in the EU and US are likely to be less adversely affected by quota phase-out, at least initially; Countries with a high reliance on merchandise exports in quota-constrained categories may find their goods uncompetitive in a quota-free trading environment. Likely examples include Bangladesh, Mauritius and Lesotho; At the same time, lead times and geographical proximity to major markets may become increasingly important, especially for those countries located close to the US and Europe (such as Mexico, the CBI countries, North African and East European countries). In the post-quota environment, producers either have to be internationally competitive, or at the very least located close to their market, reactive to changes in fashion, able to supply niche market segments and probably focused on non commodity-type and higher value-added textiles and garments; Preferential access arrangements available to unrestricted suppliers to the EU and US markets (for example under the AGOA, EBA, Cotonou and the CBI preference schemes) are likely to become less valuable over time. However, duty-free market access to the EU and US will continue to be important mitigating factors with respect to the negative impacts of quota-removal. In order to be of real benefit, preference margins available to preferential trade partners will need tralac Trade Brief No 8/2004 www.tralac.org to be sufficiently large to counter the price-advantage that many of Asia’s lowcost producers have at their disposal; The imposition of special tariffs and quotas as well as other safeguard mechanisms will continue to be available to WTO members as a trade remedy against severe market disruptions subject to certain conditions. The US is for example also permitted to apply safeguard mechanisms against Chinese exports at least until 2008 in accordance with the terms of China’s WTO accession agreement. The impact on Southern African countries is likely to be varied, considering that wide differences exist in terms of regional production capabilities and capacities as well as target markets (whether producing mainly for the domestic or foreign market). A higher degree of reliance on exports to major world markets means that countries are potentially more exposed to the negative impacts of quota removal. For example, while South Africa exports only about one third of its textile and garment production, Lesotho ships virtually all its output to the US. 13