Introduction

advertisement

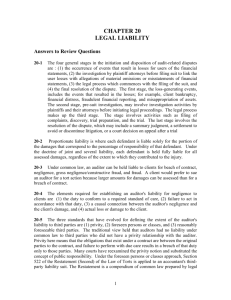

CCaappaarroo IInndduussttrriieess ppllcc vv.. D Diicckkm maann aanndd ootthheerrss 0.0. Table of Cases 1. Al Saudi Banque v. Clark Pixley, [1989] 3 All ER 361. 2. Anns v. London Borough, [1977] 2 All ER 492. 3. Candler v. Crane, Christmas & Co., [1951] 1 All ER 426. 4. Cann v. Willson, (1888) 39 ChD 39. 5. Caparo Industries plc v. Dickman, [1990] 1 All ER 568. 6. Deputy Secretary v. S.N. Das Gupta, (1955) 25 Com Cas 413. 7. Harris v. Wyre Forest District Council, [1989] 2 All ER 514. 8. Hedley Byrne and Co. v. Heller & Partners, [1963] 2 All ER 575. 9. In Re City Equitable Fire Ins. Co., [1924] All ER Rep 485. 10. In Re Kingston Cotton Mills, [1896] 2 Ch. 279. 11. In Re London and General Bank, [1895-96] All ER Rep 953. 12. Institute of Chartered Accountants v. P.K. Mukherjee, AIR 1968 SC 1104. 13. James McNaughton Papers Group Ltd. v. Hicks Anderson & Co., (1991) 2 QB 113. 14. JEB Fasteners Ltd. v. Marks Bloom & Co., [1983] 1 All ER 583. 15. London Oil Storage Co. v. Seear Hasluck & Co., (1904) 30 Acct. L.R 93. 16. Morgan Crucible Co. Plc v. Hill Samuel Bank Ltd., [1991] 1 All ER 148. 17. Smith v. Eric S Bush, [1989] 2 All ER 514. 18. Twomax Ltd. v. Dickson, McFarlane & Robinson, 1984 SLT 424. 19. Ultramares Corporation v. Touche, (1931) 255 NY 170. 1 CCaappaarroo IInndduussttrriieess ppllcc vv.. D Diicckkm maann aanndd ootthheerrss 2 1.0. Introduction The collapse of the energy monolith, Enron, and the failure of Arthur Anderson, the firm that audited Enron’s accounts, to identify the rot in the company have been one of the biggest stories to hit the market in the last one year. As a result, the law relating to the auditor’s liability has once again come into focus. In the present day setup, the sweeping changes that liberalization has brought in, along with recent instances of embezzlement, have shaken investor confidence. As a result, the role of regulators and inspectors such as auditors has been brought into prominence. Auditors are now increasingly being seen as the authorities, who can check the abuses and irregularities in the financial aspects of the companies, thus safeguarding the interests of the shareholders and investors. In view of such high expectations, “highest standard of care in accounting” has come to be expected out of the auditors and liability is sought to be imposed upon them for any deviation from the expected “high standards”. In consonance with this throughout the decades of the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s there had been an increasing trend of the judicial expansion of the number of third parties to whom an accountant can be held liable. In fact, this period has been described as the “dark ages” of liability for auditors. However, since the 1990s an international trend has emerged toward a narrower scope of accountant liability to non-clients for negligence. This significant reversal in judicial trend has been brought about by landmark decisions such as Caparo Industries plc v. Dickman,1 which is the subject matter of review in the present project report. 1 [1990] 1 All ER 568. CCaappaarroo IInndduussttrriieess ppllcc vv.. D Diicckkm maann aanndd ootthheerrss 3 2.0. Research Methodology 2.1. Aims and Objectives This project assignment aims to review the landmark judgment of the House of Lords in the case of Caparo Industries plc v. Dickman and Others. The objective of this project assignment is to examine the said judgment threadbare and to examine the importance of the same in context of the larger issue of auditor’s liability. 2.2. Scope The scope of this project is limited to the analysis of the judgment delivered by the House of Lords and to the study of auditor’s liability, especially with respect to third parties. 2.3. Research Questions What did the House of Lords in Caparo Industries plc v. Dickman and Others lay down? What is the critique, if any, of the decision of the House of Lords? What is the importance of the judgment in the larger context of auditor’s liability? What liability does an auditor owe to the various stakeholders in the society? 2.4. Style of Writing Both analytical and descriptive styles of writing have been used in this project. While an attempt has been made to analyze the dictum of the law Lords; the enunciation of the principles and the relevant case law is mainly descriptive. 2.5. Sources of Data Both primary and secondary sources of data in the form of books and case law have been used in this project. The materials used for this research paper include articles, case law and books. 2.6. Mode of Citation A uniform mode of citation has been used throughout this project. CCaappaarroo IInndduussttrriieess ppllcc vv.. D Diicckkm maann aanndd ootthheerrss 4 3.0. Caparo Industries plc v. Dickman and Others2: Case Review 3.1. Facts of the Case Fidelity Plc (hereinafter referred to as "Fidelity") was a public company, which had a listing on the Stock Exchange since 1974, specializing in the manufacture and sale of consumer electrical goods such as televisions, integrated rack units, record players, tape recorders and, subsequently, cordless telephones. On 31st March, 1983 Fidelity, issued its annual accounts for the end of the year, 31 March 1983, producing a profit of £830,000 according to the accounts. Thereafter, on 20th of July, 1983 Fidelity issued a rights issue circular proposing to increase their nominal capital by £0.3m, which contained a forecast from the directors that the profits for the year ending 31 March 1984 would be not less than £2.2m. In early March, 1984 the market price for Fidelity's ordinary 10p shares was in the range of 145p top to 120p low per share. On 12th of March, 1984 Fidelity issued a press release to the effect that in view of certain technical production difficulties, the directors took the view that the profit to the year ending 31 March 1984 would fall significantly short of £2.2m. As a result of the press release the market price of Fidelity’s shares immediately dropped to a level of 90p. On 22nd May, 1984 the directors of Fidelity announced the results for the year ended 31st March, 1984. These revealed that profits for the year fell well short of the figure which had been predicted, and this resulted in a dramatic drop in the quoted price of the shares. Fidelity's accounts for the year to 31st March, 1984 had been audited by the appellantauditors, Touche Ross. On 21st May, 1984 Touche Ross signed their annual report, which was unqualified and to that report was annexed the consolidated balance sheet and consolidated profit and loss account and the balance sheet for the year ending 31st March. The accounts had been approved by the directors on the day before the results were announced. On 12th June, 1984 they were issued to the shareholders, with notice of the annual 2 [1990] 1 All ER 568. CCaappaarroo IInndduussttrriieess ppllcc vv.. D Diicckkm maann aanndd ootthheerrss 5 general meeting, which took place on 4th of July, 1984 and at which the auditors' report was read and the accounts were adopted. Following the announcement of the results, the respondents, Caparo Industries Plc (hereinafter referred to as “Caparo”) began to purchase shares of Fidelity in the market. On 8th of June, 1984, Caparo purchased 100,000 shares but it was not registered as members of Fidelity until after 12th June, 1984, when the accounts were sent to shareholders; although they had been registered in respect of at least some of the shares which they purchased by the date of the annual general meeting, which they did not attend. On 12th June, 1984 Caparo purchased a further 50,000 shares, and by 6th of July, 1984 they had increased their holding in Fidelity to 29.9% of the issued capital. On 4th of September, 1984 Caparo made a bid for the remainder at 120p per share, that offer being increased to 125p per share on 24 September 1984. The offer was declared unconditional on 23 October 1984, and two days later Caparo announced that it had acquired 91.8% of the issued shares and proposed to acquire the balance compulsorily, which it subsequently did. Following the take-over, the respondents brought an action against the auditors of the company, alleging that: -- the accounts of Fidelity were inaccurate and misleading in that they showed a pre-tax profit of some £1.2m for the year ended 31 March 1984 when in fact there had been a loss of over £400,000, -- the auditors had been negligent in auditing the accounts, -- the respondents had purchased further shares and made their take-over bid in reliance on the audited accounts, and -- the auditors owed them a duty of care either as potential bidders for Fidelity because they ought to have foreseen that the 1984 results made Fidelity vulnerable to a take-over bid or as an existing shareholder of Fidelity interested in buying more shares. CCaappaarroo IInndduussttrriieess ppllcc vv.. D Diicckkm maann aanndd ootthheerrss 3.2. List of Dates and Events Date July, 1983 8th July, 1983 July, 1983 November, 1983 26th March, 1984 Event The directors of Fidelity announce their proposal to raise additional working capital of approximately £3.9 million by a rights issue of one new ordinary share for every three ordinary shares held at that date at a price of 145 pence per share. A press release issued by Morgan Grenfell, the Merchant Bank which underwrote the rights issue, states that: "Although it is relatively early in the financial year, the directors feel able to forecast that, in the absence of unforeseen circumstances, pre-tax profits for the year ending 31st March 1984 will be not less than £2.2 million. The bases and assumptions on which this forecast is made are contained in a circular setting out the details of the issue which is to be despatched to shareholders later today." In the same press release the directors announce their intention to recommend, in respect of the year ending 31st March 1984, dividends of not less than three pence per share on the share capital as enlarged by the proposed rights issue Morgan Grenfell and Touche Ross, the company's auditors, each write a comfort letter in respect of the profit forecast of £2.2 million. The unaudited half-year results to 30th September 1983 show a pretax profit of £766,000. It is also announced that, in view of the satisfactory results and the prospect of good trading conditions, the directors were recommending the payment of an interim dividend of one pence per ordinary share payable on 18th January 1984. Touche Ross writes to Morgan Grenfell a letter saying that they had discussed and reviewed 6 CCaappaarroo IInndduussttrriieess ppllcc vv.. D Diicckkm maann aanndd ootthheerrss 12th March, 1984 Fidelity's revised estimate of profits for the year ending 31st March 1984, which were £1.395 million for the group (being the company and its subsidiary Highfield Cabinets Ltd), contrasted with the earlier forecast of £3.385 million. The letter states: "Our principal findings and conclusions are: -- that the group is highly unlikely to make a pre-tax profit of £1.395 million for the year to 31 March 1984. The Chairman and Chief Executive informs us that he has reservations as to the final figure because of the possible effect of stock adjustments. We agree that given the continued lack of an integrated detailed costing system a forecast in advance of a full physical stock take at 31 March is extremely difficult. We also feel that the profit estimate will be very difficult to achieve due to concerns in the following areas…. -- that the pre-tax forecast included in the rights issue document of £2.2 million was not made recklessly or irresponsibly, -- that at the time of the interim announcement in November 1983 the board were aware that the estimated out turn for the year would be significantly below the £3,385,000 initial internal forecast. They did not know, and probably could not have been expected to know, the severity of problems which were to arise soon thereafter, so that not even the £2.2 million pre-tax forecast would be achieved." Morgan Grenfell issues a press release stating that the directors were now of the opinion that the pre-tax profit for year ending 31st March 1984 would fall significantly short of that of £2.2 million forecast at the time of the rights issue. Explanations are given for this 7 CCaappaarroo IInndduussttrriieess ppllcc vv.. D Diicckkm maann aanndd ootthheerrss 21st May, 1984 22nd May, 1984 1st June, 1984 8th June, 1984 8th June, 1984 12th June, 1984 12th June, 1984 shortfall, but the notice concludes, in words that foreshadow those of the First Defendant in the Annual Report issued three months later, that the difficulties which had led to the shortfall had been overcome. The board approves the accounts for the year ending 31st March 1984 to which Touche Ross, the auditors, have given a clean certificate. The results are announced, including the pre-tax profit figure of £1.310. The price of the company’s share falls to 63 pence from the previous high of 143 pence on 1st March, 1984. Deric Holmes of Le Mare Martin, stockbrokers, who had been consulted by the Plaintiffs ("Caparo"), approach Mr Leek, Caparo's Chief Executive, to discuss Fidelity. Caparo makes their first purchase of 100,000 Fidelity shares at 70 pence per share. Caparo purchases a further 50,000 shares at 73 pence. Fidelity's Annual Report and Financial Statement are issued to shareholders. The Chairman's Report includes the following: "Results Profits before tax rose from £80,000 to £1,310,000 continuing the consolidation in the recovery started last year. Sales increased from £33,388,000 to £41,076,000, an improvement of 23 per cent. These figures would be satisfactory in normal circumstances; however, they are disappointing in view of the shortfall in profits on the forecast made at the time of the rights issue in July 1983. The shortfall was caused by unforeseen technical and production difficulties that we encountered with the introduction of a new chassis used throughout the range of colour televisions. In 8 CCaappaarroo IInndduussttrriieess ppllcc vv.. D Diicckkm maann aanndd ootthheerrss 18th June, 1984 20th June, 1984 21st June, 1984 4th July, 1984 9th July, 1984 18th July, 1984 30th July, 1984 4th Sept., 1984 addition, unexpected delays were experienced with the tests specification for the cordless telephones which had to be resolved before the production programme could continue. As a result, approximately one-third of the planned production will not be completed before September this year. These difficulties have now been overcome, and production of the cordless telephones and colour televisions is going according to plan." Caparo notifies the Stock Exchange and Fidelity that it owns 5.8 per cent of the shares in Fidelity, as required by the City Code. Fidelity appointes the First Defendant and Mr Ouaknin, Finance Director, Fidelity, as a committee to deal with offers for the shares. The First Defendant writes a letter to shareholders saying that the prices paid for its shares by Caparo "seriously undervalue the true worth of your company. Furthermore, the current share price of 95 pence does not in any way reflect your company's excellent long-term prospects . . ." Fidelity's annual general meeting is held and the shareholders approve the accounts. Caparo announces that it holds 18.4 per cent of the shares. The First Defendant reports to a board meeting of Fidelity that Caparo had no intention of making a bid. Caparo announces that it has acquired 29.9 per cent of the shares in Fidelity. Caparo announces that it had that day bought a further 270,000 shares at 120 pence per share and announces its offer, subject to further terms and conditions, of 120 pence for each ordinary share. 9 CCaappaarroo IInndduussttrriieess ppllcc vv.. D Diicckkm maann aanndd ootthheerrss 5th Sept., 1984 21st Sept., 1984 24th Sept., 1984 3rd October, 1984 22nd Oct., 1984 23rd Oct., 1984 24th Oct., 1984 31st Dec., 1988 24th July, 1985 10 The board of Fidelity issues a press release through Morgan Grenfell in which it is stated, inter alia, that: "The board of Fidelity . . . has no hesitation in unanimously concluding that the terms of this unsolicited offer significantly undervalue Fidelity's longer term potential . . . and that this offer will not be recommended to shareholders." An agreement in principle is reached between Caparo and Fidelity that Fidelity's board should recommend Caparo's increased offer of 125 pence per share. Kleinwort Benson, who are acting for Caparo, announce that an agreement had been reached. Kleinwort Benson circulate a formal recommended offer Fidelity's shareholders. The offer is approved by Caparo's shareholders at an extraordinary general meeting. The offer is declared unconditional in all respects. At a meeting of the board of Fidelity, Mr Wiltshire resigns as Chairman and director of Fidelity. Mr Paul Caparo is elected Chairman in his place and Mr Leek and Doctor Hanna, both also of Caparo, are appointed directors. Caparo closes down Fidelity's operations. Caparo issues a writ against the defendants, with the Statement of Claim specially endorsed upon it. 3.3. Question For Consideration With the issuance of a writ indorsed with a statement of claim by Caparo claiming damages against the third defendants, Touch Ross and Co for negligence, the preliminary question that came up for consideration of the Court was: “Whether on the facts set out in the relevant paragraphs of the Statement of Claim, the Third Defendants, Touche Ross & Co., owed a duty of care to the Plaintiffs, Caparo Industries plc, CCaappaarroo IInndduussttrriieess ppllcc vv.. D Diicckkm maann aanndd ootthheerrss 11 (a) as potential investors in Fidelity Plc or (b) as shareholders in Fidelity Plc from 8 June 1984 and/or from 12 June 1984 in respect of the audit of the accounts of Fidelity Plc for the year ended 31 March 1984 published on 12 June 1984.” 3.4. Basis of the Claim The claim against the Touche Ross & Co, who were the auditors of the company Fidelity was based on the contention that: Touche Ross, as auditors of Fidelity carrying out their functions as auditors and certifiers of the accounts in April and May 1984, owed a duty of care to investors and potential investors, and in particular to Caparo, in respect of the audit and certification of the accounts because: (a) Touche Ross knew or ought to have known – (i) that in early March 1984 a press release had been issued stating that profits for the financial year would fall significantly short of £2.2m (ii) that Fidelity's share price fell from 143p per share on 1st March 1984 to 75p per share on 2nd April 1984 (iii) that Fidelity required financial assistance. (b) Touche Ross therefore ought to have foreseen that Fidelity was vulnerable to a takeover bid and that persons such as Caparo might well rely on the accounts for the purpose of deciding whether to take over Fidelity and might well suffer loss if the accounts were inaccurate. 3.5. Decisions of the Lower Courts 3.5.1. Decision of the Queen’s Bench On the trial of the preliminary issue Sir Neil Lawson, sitting as a judge of the Queen's Bench Division, held (i) that the auditors owed no duty at common law to Caparo as investors, as there was no close or direct relationship that could give rise to a duty of care, and (ii) that, whilst auditors might owe statutory duties to shareholders as a class, there was no common law duty to individual shareholders such as would enable an individual shareholder to recover damages for loss sustained by him in acting in reliance on the audited accounts. 3.5.2. Decision of the Court of Appeal CCaappaarroo IInndduussttrriieess ppllcc vv.. D Diicckkm maann aanndd ootthheerrss 12 Caparo appealed to the Court of Appeal, which, by a majority (O'Connor LJ dissenting) allowed the appeal holding that (i) there was no relationship between an auditor and a potential investor sufficiently proximate to give rise to a duty of care at common law, but (ii) an auditor had a duty of care to individual shareholders, so that an individual shareholder who suffered loss by acting in reliance on negligently prepared accounts, whether by selling or retaining his shares or by purchasing additional shares, was entitled to recover in tort. From the decision of the Court of Appeal the auditors appealed to the House of Lords, with the leave of the Court of Appeal, and Caparo cross-appealed against the rejection by the Court of Appeal of their claim that the auditors owed them a duty of care as potential investors. 3.6. Ratio Decidendi of the Pronouncement of Law Lords The House of Lords after a careful examination of landmark cases on negligent misstatement and the criteria to be used to determine the existence and the scope of the duty of care, unanimously held that: (1) The three criteria for the imposition of a duty of care were (a) foreseeability of damage, (b) proximity of relationship, and (c) the reasonableness or otherwise of imposing a duty. (2) In determining whether there was a relationship of proximity between the parties; the court, guided by situations in which the existence, scope and limits of a duty of care had previously been held to exist rather than by a single general principle, would determine whether the particular damage suffered was the kind of damage which the defendant was under a duty to prevent and whether there were circumstances from which the court could pragmatically conclude that a duty of care existed: (3) Where a statement put into more or less general circulation might foreseeably be relied on by strangers for any one of a variety of different purposes which the maker of the statement had no specific reason to anticipate, there was no relationship of proximity between the maker of the statement and any person relying on it; unless it was shown that the maker knew that his statement would be communicated to the person relying on it, either as an individual or as a member of an identifiable class, specifically in connection with a particular transaction or a transaction of a particular kind and that that person would be very likely to rely on it for the purpose of deciding whether to enter into that transaction (4) The auditor of a public company's accounts owed no duty of care to a member of the public at large, who relied on the accounts to buy shares in the company, because the court would not deduce a relationship of proximity between the auditor and a member of the public when to do so would give rise to unlimited liability on the part of the auditor. CCaappaarroo IInndduussttrriieess ppllcc vv.. D Diicckkm maann aanndd ootthheerrss 13 (5) An auditor owed no duty of care to an individual shareholder in the company who wished to buy more shares in the company, since an individual shareholder was in no better position than a member of the public at large and the auditor's statutory duty to prepare accounts was owed to the body of shareholders as a whole. (6) The purpose for which accounts are prepared and audited is to enable the shareholders as a body to exercise informed control of the company and not to enable individual shareholders to buy shares with a view to profit. Hence, it followed that the auditors did not owe a duty of care to the respondents either as shareholders or as potential investors in the company. The appeal was therefore, allowed and the cross-appeal dismissed. 3.7. Analysis of the Judgment This decision of the House of Lords, in which Lords Bridge, Oliver and Jauncey set out at length the reasons behind their decision, has come to be considered as an important landmark in the context of the law on negligent misstatements by professional people, which cause economic loss. The unanimous decision of the House of Lords has the following characteristics: Their Lordships in the instant case were reluctant to extend the situations where a duty of care for negligent statements may arise beyond those recognised by the authorities and thus rejected the more modern approach of applying recognised principles to a situation regardless of whether or not it is covered by authority. They agreed that foreseeability alone was not sufficient to impose such a duty and that the requiste relationship of proximity should also be present to limit what would otherwise be an unlimited duty of care owed by auditors for the accuracy of their accounts to all who may foreseeably rely on them. Lord Bridge found that the limit imposed upon the liability for causing economic loss, rested in the necessity to prove, ‘as an essential ingredient of the “proximity” between the plaintiff and the defendant, that the defendant knew that his statement would be communicated to the plaintiff… specifically in connection with a particular transaction…. (e.g. in a prospectus inviting investment) and that the plaintiff would be very likely to rely on it for the purpose of deciding whether or not to enter upon that transaction….’ Lord Oliver agreed there was no support for the proposition that the relationship of proximity is to be extended beyond circumstances in which advice is tendered for the CCaappaarroo IInndduussttrriieess ppllcc vv.. D Diicckkm maann aanndd ootthheerrss purpose of the particular transaction and the adviser knows or ought to know that it will be relied on by a particular person in connection with that transaction. Lord Jauncey considered that the possibility of reliance on a statement for an unspecified purpose will not impose a duty of care on the maker of the addressee. Even if the reliance was probable, regard must be had to the transaction of the purpose of which the statement was made. Their Lordships referred to Cann v. Willson,3 Ultramares Corporation v. Touche,4 the dissenting judgment of Lord Denning in Candler v. Crane, Christmas & Co.5, approved by the House of Lords in Hedley Byrne and Co. v. Heller & Partners 6 and the two appeals of Smith v. Eric S Bush and Harris v. Wyre Forest District Council, 7 both of which had been heard together by the House of Lords, as their authority for these propositions. Their Lordships felt that the ratio of the above mentioned cases led to the conclusion that auditors owe no duty of care to members of the public at large who rely on the accounts to buy shares, as, if it did, the duty would then extend to all who rely on the accounts such as investors deciding to buy shares, lenders or merchants extending credit. Even the fact that a company is vulnerable to take-over at the time the accounts are prepared cannot per se create the relationship of proximity. In fact, in Al Saudi Banque v. Clark Pixley,8 Justice Miller had rejected a claim that auditors owed a duty of care to a bank and their Lordships agreed with the decision. Their Lordships questioned the purpose behind the statutory requirement for an annual audit, and concluded that it is to enable shareholders to review the past management of the company and to exercise their rights to influence future management. They saw nothing in the statutory duties of an auditor to suggest that they were intended to protect the interests of the public at large or investors in the market in particular. The statutory duty was, therefore, owed to shareholders as a body and not as individuals. Since an auditor owed no duty to an individual shareholder, it followed that he could owe no duty to a potential investor. 3 (1888) 39 ChD 39. (1931) 255 NY 170. 5 [1951] 1 All ER 426. 6 [1963] 2 All ER 575. 7 [1989] 2 All ER 514. 8 [1989] 3 All ER 361. 4 14 CCaappaarroo IInndduussttrriieess ppllcc vv.. D Diicckkm maann aanndd ootthheerrss 15 Their Lordships were not prepared to widen the scope of duty to include loss caused to an individual by reliance upon the accounts for a purpose for which they were not supplied and were not intended, as to do so would be to extend it beyond the limit deducible from the previous decisions of the House of Lords. The judgment however, does not make clear whether there is a duty to protect individual shareholders from losses in the value of the shares they hold. 3.8. Critique of the Judgment This decision of law Lords has been the subject of consideration of a number of jurists around the world. Some of them have criticized this judgment of the House of Lords on the ground that the annual accounts of a company and the audit certificates are public documents and accordingly, persons dealing with the company had constructive notice of the state of affairs of the company as these documents are filed with the Registrar of Companies. Therefore, auditors and accountants should be responsible to investors, creditors and others who deal with the company accounts. However, the Report of the Committee on the Financial Aspects of Corporate Governance9 while acknowledging the presence of such criticism has stated that: “5.32 … The case has aroused controversy because it exposed two widely held misconceptions: (a) that the audit report is a guarantee to the accuracy of the accounts, and perhaps even as to the soundness of the company; (b) that anyone (including investors and creditors) can rely on the audit, not only in a general sense but also very specifically by being able to sue the auditors if they are negligent. In deciding the case, the House of Lords studied with great care the complex issues involved in balancing the interests of the parties involved and the public interest in having a fair, viable and affordable system. The size of auditor’s potential liabilities, the difficulties in defining wider liability in any fair yet practicable way, and the likely difficulties in establishing whether third-party losses were in fact due to reliance on the accounts were among the principle concerns underlying the conclusions reached by the House of Lords. Bearing in mind the wide range of users of accounts, the Committee is unablke to see how the House of Lords could have broadened the boundaries of the auditor’s legal duty of care without giving rise ‘to a liability in an indeterminate amount for an indeterminate time to an indeterminate class’.” Nonetheless, Suzanie Chau in her article, while celebrating the decision of the law Lords has validly criticized the judgment in the following words: 9 http://www.worldbank.org/html/fpd/privatesector/cg/docs/cadbury.pdf. visited on 15th May, 2002. This report is popularly known as the ‘Cadbury Report’. CCaappaarroo IInndduussttrriieess ppllcc vv.. D Diicckkm maann aanndd ootthheerrss 16 “It is submitted that this limitation of duty to shareholders as a single body can produce anomalous results in purely economic terms. Contrast the founder share-holder who holds on to shares and paid little or no regard to the financial management of the enterprise with the shareholder who buys shares as a price inflated as a result of audit negligence and who sells the shares after its discovery and the subsequent drop in share price but before any action is instituted. If it was subsequently decided that the auditors were negligent and that the company should be compensated, would that founder shareholder not be enriched by the company’s successful suit against the auditor at the expense of the (remediless) shareholder who sold? It can hardly be argued that the founder shareholder relied on the audit report and it is difficult to see what economic loss the auditor’s negligence has caused him. What about shareholders who purchased shares prior to the publication of the audit report but who are now members of the company and therefore part of the body of the shareholders which is successful in its action against the auditor? Is their enrichment not coincidental and hence, possibly unjust?”10 Suzanie Chua, “The Auditor’s Liability in Negligence in Respect of the Audit Report”, Journal of Business Laws, 1995 at 1. 10 CCaappaarroo IInndduussttrriieess ppllcc vv.. D Diicckkm maann aanndd ootthheerrss 17 4.0. Caparo in Context: Importance of the Judgment 4.1. Legal Pronouncements before Caparo Prior to 1964, it was quite onerous for a third party user of financial statements to sue an accountant in the United Kingdom for negligent misstatements. 11 This was essentially because of the prevailing view that there is no liability for negligent misrepresentation made by one person to another who had relied upon it to his detriment, in the absence of any contractual or fiduciary relationship between the parties or fraud.12 An example of this can be found in the case of Candler v. Crane, Christmas & Co.,13 wherein the court applied the “privity doctrine”.14 However, disagreeing with the majority Lord Justice Denning wrote a strong dissenting opinion, which later gained widespread approval.15 In fact, in Hedley Byrne & Co. v. Heller & Partners Ltd.16 the House of Lords adopted Lord Denning's argument in establishing that a third party who had relied to his detriment on a negligent misstatement could sue despite the absence of privity of contract.17 In that case, Heller & Partners Ltd., a merchant banking firm, provided incorrect data in response to a request from National Provincial Bank for credit information on Easipower Ltd. John G. Fleming, “The Negligent Auditor and Shareholders”, L.Q. Rev. July 1990 at 349. In Candler v. Crane, Christmas & Co., [1951] 1 All ER 426, a majority of the Court of appeal dismissed the claim of the plaintiff who had invested money a company, in reliance upon the accounts prepared by the accountants and consequently lost his investment. 13 [1951] 1 All ER 426. 14 The essence of the privity doctrine is that a third party not in privity or in contract with the auditor cannot recover damages for negligence. 15 In his dissenting judgment Lord Denning suggested three conditions for the creation of a duty of care in tort for professionals. First, the advice must be given by one whose profession it is to give advice upon which others rely in the ordinary course of business. Second, it must be known to the adviser that the advice would be communicated to the plaintiff in order to induce him to adopt a particular course of action. Third, the advice must be relied upon for the purpose of the particular transaction for which it was known to the advisers that the advice was required. However, Lord Denning did not consider these conditions as necessarily exhaustive criteria for the existence of a duty. 16 [1963] 1 All ER 575. 17 Hedley Byrne has been acknowledged as the first significant inroad into the general denial of the ability of nonclients to sue accountants for negligent misstatements. 11 12 CCaappaarroo IInndduussttrriieess ppllcc vv.. D Diicckkm maann aanndd ootthheerrss 18 Heller & Partners knew the credit information would be communicated to a specific unidentified customer of National Provincial Bank. In reliance on the credit information, Hedley Byrne, the unidentified customer, extended credit for services rendered to Easipower Ltd. Easipower then went into liquidation. The House of Lords ruled that accountants and other professionals owed a duty to any third person with whom a "special relationship" existed. It opined that a "special relationship" arose in Hedley Byrne because of a "voluntary assumption of responsibility" by the defendant to the plaintiff. The law Lords agreed that a "special relationship" includes more than a fiduciary or contractual relationship; however, they failed to specify criteria for deciding when a "special relationship" arises, and thus, when a duty of care comes into existence. The clear trend in the law of negligent misstatement immediately after Hedley Byrne was toward expanding the scope of duty to more third parties.18 In general, the basis of the scope of duty or "special relationship" moved from "voluntary assumption" of responsibility by the defendant to the third party's "reasonable reliance" to "foreseeability."19 The application of the foreseeability concept gained currency in Anns v. London Borough20. Although the facts of Anns do not deal with accountants, the case established a twoprong test of liability for negligent misstatements. “The first prong asks whether the defendant's carelessness may be likely to injure the suing party: First, one has to ask whether, as between the alleged wrongdoer and the person who has suffered damage there is a sufficient relationship of proximity or neighbourhood such that, in the reasonable contemplation of the former, carelessness on his part may be likely to cause damage to the latter-in which case a prima facie duty of care arises. If the first question is answered affirmatively, a duty of care arises. The second prong examines any considerations that could reduce or eliminate the scope of the duty owed: "[I]t is necessary to consider whether there are any considerations which K.R. Chandratre, “Auditors duty of care and liability for negligence: Recent Judicial Exposition”, [2002] 35 SCL (Mag.) at 109. 19 Id. 20 [1977] 2 All ER 492. 18 CCaappaarroo IInndduussttrriieess ppllcc vv.. D Diicckkm maann aanndd ootthheerrss 19 ought to negative, or to reduce or limit the scope of the duty or the class of persons to whom it is owed or the damages to which a breach of it may give rise."”21 The practical effect of the decision in the case of Anns was to render almost any sequence of events foreseeable, leaving any limitation on liability to the vagaries of ad hoc policy assessments freed from precedential constraints.22 In the context of accountants' liability to non-clients for negligence, the Anns foreseeability test was applied in JEB Fasteners Ltd. v. Marks Bloom & Co.23 In that case, JEB Fasteners acquired all the shares in a private company having relied on an unqualified audit report produced by accountants Marks Bloom. The financial statements contained numerous errors and thus, the stock acquired by JEB was overvalued. Although the auditors were unaware of any specific takeover bidder at the date of the audit, they later became fully aware of the identity and progress of the bidder and were in touch with him and supplied relevant information. JEB Fasteners sued the auditors for damages claiming the provision of negligent auditing services. The Queen's Bench Division ruled that the appropriate test for establishing a duty of care is whether the auditors knew or reasonably should have known that a person might rely on the audited financial statements for making a decision. The Anns foreseeability test was also followed in the Outer House of Session in Scotland in Twomax Ltd. v. Dickson, McFarlane & Robinson24. In that case the court dealt with three separate legal claims from investors who had bought shares in a closely held company. The firm went into bankruptcy shortly after the investors acquired their shares. As in JEB Fasteners, the defendant accountants were found to owe a duty of care to the plaintiff investors. The fact that the accountants knew or should have known that the potential investors might rely on the audited financial statements was deemed sufficient to create proximity, thus giving rise to a duty of care. Carl Pacini et al., “At The Interface Of Law And Accounting: An Examination Of A Trend Toward A Reduction In The Scope Of Auditor Liability To Third Parties In The Common Law Countries”, 37 Am. Bus. L.J. at 171. 22 Id. 23 [1983] 1 All ER 583. 24 1984 SLT 424 as cited in Carl Pacini et al., “At The Interface Of Law And Accounting: An Examination Of A Trend Toward A Reduction In The Scope Of Auditor Liability To Third Parties In The Common Law Countries”, 37 Am. Bus. L.J. at 184. 21 CCaappaarroo IInndduussttrriieess ppllcc vv.. D Diicckkm maann aanndd ootthheerrss 20 4.2. Caparo and After The widening ambit of accountant liability to third parties was arrested in Caparo Industries Plc v. Dickman.25 As has been already detailed, in a unanimous decision, the House of Lords ruled that an auditor of a public company, in the absence of special circumstances, owes no duty of care to an outside investor or an existing shareholder who buys stock in reliance on a statutory audit. In the process, the court fashioned a three-prong test for an auditor's duty of care, which has been explained earlier. Since Caparo, the courts have continued to limit the imposition on auditors of a duty to non-clients for negligent misstatements. A case in point is James McNaughton Papers Group Ltd. v. Hicks Anderson & Co.26. The facts involved the plaintiff's takeover of its rival, MK, which had been in financial distress. MK's accountants prepared draft financial statements, which were shown to the plaintiff. Reversing the trial court judge, the English Court of Appeal found that the accountants owed no duty of care to the plaintiff. In doing so, the court cited Caparo and noted that in England, a "restrictive approach is now adopted to any extension of the scope of the duty of care beyond the person directly intended by the maker of the statement to act on it." In the case in question, Lord Justice Neill's opined that the important factors to consider in addressing the scope of duty question are the purpose for which the information was prepared and communicated, the relationship between the accountant, client, and third party, the size of the class to which the third party belongs, and the extent of the third party's reliance. One of the most significant post-Caparo decisions is Morgan Crucible Co. Plc v. Hill Samuel Bank Ltd. 27 . In this case, the plaintiff sued a target firm's auditors and investment bankers. First Castle Electronics, the takeover target, and its investment bankers released a circular stating that an initial hostile takeover bid was too low because it did not place sufficient value on a projected profit rise. First Castle's accountants had issued a letter, contained in the circular, stating that the forecast had been prepared in accordance with First Castle's accounting policies. The acquiring firm raised its offer price (the "second takeover bid") but later claimed the profit forecast was negligently prepared. The English Court of Appeal ruled, as in Caparo, that the accountants did not owe a duty of care to the plaintiff before the first takeover 25 [1990] 1 All ER 568. (1991) 2 QB 113. 27 [1991] 1 All ER 148. 26 CCaappaarroo IInndduussttrriieess ppllcc vv.. D Diicckkm maann aanndd ootthheerrss 21 bid. Significantly, in Caparo, all the accountant's representations relied on by the plaintiff had been made before an identified bidder had emerged. Although the English Court of Appeal did not decide that a duty of care arose with regard to the second takeover bid, it indicated such a claim was not bound to fail. The reasons were that it was foreseeable the plaintiff would suffer a loss if the profit forecast was inaccurate, the defendant accountants knew the identity of the plaintiff and intended the plaintiff to rely, and much of the information in the profit forecast was available only to the defendant. 4.3 Importance of the Judgment The decision of the House of Lords in Caparo narrowed the scope of accountant liability to third parties for negligent misstatements. It has now been established that the auditor of a public firm, absent special circumstances, does not owe a duty of care to an outside investor or an existing shareholder who buys stock in reliance on audited financial statements. As a result of Caparo accountant liability for negligent misstatements has now come to be confined to cases where it can be established that the accountant knew his work product would be communicated to a non-client, either individually or as a member of a limited class, and the third party would rely on the work product in connection with a particular transaction. CCaappaarroo IInndduussttrriieess ppllcc vv.. D Diicckkm maann aanndd ootthheerrss 22 5.0. Auditor’s Liability for Negligence The complex question of the liability of the auditor to various groups of people, especially third parties, cannot be isolated from the position, role and the responsibilities, which the auditor has been assigned by the law and judiciary. 5.1. The Auditor under the Framework of Company Law 5.1.1. Auditor vis-à-vis Shareholders The Calcutta High Court in the case of Deputy Secretary v. S.N. Das Gupta28, while elucidating on the relationship between the auditors and the shareholders has stated that: “A joint stock company carries on business with capital furnished by persons who buy its shares. The owners of the capital are, however, not in direct control of its application, which is left to the executive of the company. In those circumstances, some arrangement is obviously called for by which those who provide the capital know periodically what is being done with their money, how the affairs of the company stand and what the present value of their investment is. The Companies Act, therefore, provides for the employment of an auditor who is the servant of the shareholder and whose duty is to examine the affairs of the company on their behalf at the end of a year and to report to them what he has found. That examination by an independent agency such as the auditors is practically the only safeguard which the shareholders have against the enterprise being carried on in an unbusiness like way or their money being misapplied or misappropriated without their knowing anything about it. The Act provides the safeguard in two forms. It makes the duty of the auditor to give an expression of opinion on certain specified matters of a vital character and it makes him liable, along with the directors, for misfeasance, if he fails to perform his duties as required by law and the approved audit procedure.” Thus, auditors have a fiduciary relationship vis-a-vis the shareholders as a body and ‘the auditor is like a trustee for shareholders.” 29 5.1.2. Auditor as an Officer of the Company The auditor is an officer of the company only for limited purposes as given in Section 2 (30) of the Companies Act, 1956 30 and therefore can not be prosecuted for 28 (1955) 25 Com Cas 413. Institute of Chartered Accountants v. P.K. Mukherjee, AIR 1968 SC 1104. 30 Section 2(30) states that the auditor is an officer of the Company as far as winding up is concerned and gives a list of provisions under which the auditor is considered to be an officer of the company. These 29 CCaappaarroo IInndduussttrriieess ppllcc vv.. D Diicckkm maann aanndd ootthheerrss contravention of the provisions of the Company Act, 1956 reagarding the maintenance of the books of account, preparation of financial statements and their audit. 5.1.3. Auditor as a Watchdog In Re Kingston Cotton Mills31 case the Court held that while it is true that the auditors primary function is to look into the account books of the company, it is also the law of the land that where there is adequate material before the auditor to arouse suspicion, he should probe into the matter in detail and attempt to get under the skin of the problem and thus help resolve the issue.32 The Court stated in the above mentioned case that: “an auditor is not bound to be a detective or … to approach his work with suspicion. He is a watchdog and not a bloodhound. He is justified in believing the tried servants of the company in whom confidence is placed by the company. He is entitled to assume that they are honest and rely on their representations, provided he takes reasonable care. If there is anything calculated to excite suspicion, he should probe it to the bottom, but in the absence of anything of that kind he is only bound to be reasonably cautious and careful. His duty is verification and not detection. If in the course of his sniffing around he detects something suspicious he must track it down to verify it.” 5.1.4. Duties of Auditors in Carrying Out Audit Duty Of Care In the case of In Re London and General Bank, 33 the Court held: The duty of the auditor “is to ascertain and state the true financial position of the company at the time of the audit, and his duty is confined to that. He discharges his duty by examining the books the company. But he does not discharge his duty by doing this without inquiry and without taking any trouble to see that the books themselves show the company’s true position.” Thus, in exercise of his duty, an auditor must use reasonable care and skill, and must certify to the shareholders only what he believes to be true. Essentially, an auditor should give a true and fair view of the company’s annual financial statement. provisions are section 477, section 478, section 539, section 543, section 545, section 625, and section 633. 31 [1896] 2 Ch. 279. 32 Institute of Chartered Accountants v. P.K. Mukherjee, AIR 1968 SC 1104. 33 [1895-96] All ER Rep 953. 23 CCaappaarroo IInndduussttrriieess ppllcc vv.. D Diicckkm maann aanndd ootthheerrss Standard of Care No legislation or the normal contract of engagement specifies the standard of care required of an auditor.34 However, various courts have laid down that the auditor must exercise reasonable skill and care in the discharge of his duties. This has been best described in the following words of Romer J. in City Equitable Fire Ins. Co., Re:35 “He must be honest, that is, he must not certify what he does not believe to be true and he must take reasonable care and skill before he believes that what he certifies is true. What is reasonable care in any particular case must depend upon the circumstances of that case. Where there is nothing to excite suspicion very little inquiry will be reasonably sufficient. Where suspicion is aroused more care is obviously necessary; but, still an auditor is not bound to exercise more than reasonable care and skill even in case of suspicion and he is perfectly justified in acting on the opinion of an expert where special knowledge is required.” 5.2. Auditor’s Liability 5.2.1. General The auditor holds himself out to the public as an expert, willing to perform skilled services for reward. Accordingly, the law imposes exacting obligations on him to carry out the work to an acceptable standard of competence and with due care. 5.2.2. Basis of General Liability There may be instances where the auditor is negligent in performing the duties and obligations imposed upon him by law. Such negligence on the part of the auditor in performing his duty in that capacity may give rise to a liability, either in tort or in contract. If it is proved that the auditor had failed to perform his work with due care and skill, he can be held personally liable in damages to the extent of the loss suffered as a result of his default by the client or other person relying on him to whom he may owe a duty of care.36 While the liability of the auditor for his negligent acts or misstatements in contract is based on a breach of contract with the client, the general liability of an auditor, or for 34 S.M. Shah, Lectures on Company Law (19th Ed., Bombay: N.M. Tripathi Pvt. Ltd., 1990) at 382. [1924] All ER Rep 485. 36 Jon H. Holyoak, “Accountancy and Negligence”, Journal of Business Laws, 1986 at 121. 35 24 CCaappaarroo IInndduussttrriieess ppllcc vv.. D Diicckkm maann aanndd ootthheerrss 25 that matter, of a member of any other skilled and learned profession in Tort is based on the principle of holding out. In fact, in Cooley on Torts, it has been stated that: “In all those employments where peculiar skill is requisite, if one offers his services, he is understood as holding himself out to the public as possessing the degree of skill commonly possessed by others in the same employment, and if his pretensions are unfounded, he commits a species of fraud upon every man who employ him in reliance on his public profession.”37 5.2.3. Auditor’s Liability to the Company Auditors are appointed by the company and though the auditors might be making their reports to the members of the company, they owe a contractual duty of care to the company itself. Thus, a negligent audit on the part of the auditors may give rise to the auditor’s liability to the company for the loss arising from his negligence. However, an auditor’s liability to the company may also arise in tort. To hold the Auditors liable for negligence at common law it is necessary for the company to show that loss has been caused to the company through the failure of the Auditors to perform their duty with reasonable care and skill.38 Thus, in pursuance to these principles in London Oil Storage Co. v. Seear Hasluck & Co.39 the auditor was held liable and ordered to compensate the company for the losses suffered by the company on account of the auditor’s failure to verify one of the assets in the balance sheet. 5.2.4. Auditor’s Liability to the Shareholders It was acknowledged by the House of Lords in the case of Caparo Industries plc v. Dickman and others,40 that the Companies Act established a relationship between the auditors and the shareholders of a company upon which the shareholders are entitled to protection of their interest. 37 As quoted in A. Ramaiya, Guide to Companies Act (Part II, 15th Ed., Nagpur: Wadhwa and Company, 2001) at 708. 38 A. Ramaiya, Guide to Companies Act (Part II, 15th Ed., Nagpur: Wadhwa and Company, 2001) at 710. 39 (1904) 30 Acct. L.R 93 Palmer's Company Law (Clive M. Schmitthoff Ed., 24th Ed., London: Stevens & Sons Limited, 1987) at 1091. 40 [1990] 1 All ER 568. CCaappaarroo IInndduussttrriieess ppllcc vv.. D Diicckkm maann aanndd ootthheerrss 26 Often, the interest of the shareholders in the proper management of the company’s affairs is indistinguishable from the interest of the company itself, that is, the shareholders as a body.41 Thus, it has been held that the auditor’s client is the body of shareholders, that is, the company, and it is to the company that the auditors will be recognized, in law, to owe a duty of care and the auditors owe no duty of care to an individual shareholder in the company. 5.2.5. Auditor’s Liability to Third parties There was formerly the prevailing view that there is no liability for negligent misrepresentation made by one person to another who had relied upon it to his detriment, in the absence of any contractual or fiduciary relationship between the parties. 42 This position was however, overruled in Hedley Byrne & Co. v. Heller & Partners43 where it was held that in certain circumstances contractual liability could be incurred for a negligent misstatement made by one person to another, even in the absence of any contractual or fiduciary relationship. Later, in Caparo Industries plc v. Dickman and others, 44 the scope of accountant liability to third parties for negligent misstatements was narrowed.45 Thus, the auditor of a public firm, absent special circumstances, does not owe a duty of care to an outside investor or an existing shareholder who buys stock in reliance on audited financial statements. Accountant liability for negligent misstatements is confined to cases where it can be established that the accountant knew his work product would be communicated to a nonclient, either individually or as a member of a limited class, and the third party would rely on the work product in connection with a particular transaction. Suzanie Chua, “The Auditor’s Liability in Negligence in Respect of the Audit Report”, Journal of Business Laws, 1995 at 16. 42 In Candler v. Crane, Christmas & Co., [1951] 1 All ER 526, a ajority of the Court of appeal dismissed the claim of the plaintiff who had invested money a company, in reliance upon the accounts prepared by the accountants and consequently lost his investment. 43 [1963] 2 All ER 575. 44 [1990] 1 All ER 568. 45 For a detailed discussion refer to Section 4.0. of this project-report. 41 CCaappaarroo IInndduussttrriieess ppllcc vv.. D Diicckkm maann aanndd ootthheerrss 27 CCaappaarroo IInndduussttrriieess ppllcc vv.. D Diicckkm maann aanndd ootthheerrss 28 6.0. Conclusion In a marked departure from the "dark ages" of liability for auditors, there has been a growing trend toward a narrower scope of accountant liability for negligence. This is a significant development given that only about a decade ago, there had been an identifiable trend toward expanding the auditor's liability for negligent misstatements. The trend towards expanding the auditor's liability to third parties, which emerged during the 1970s and 1980s, moved the scope of duty away from blind adherence to a privity or nearprivity standard to a version of the reasonable foreseeability rule. This expansion of accountant liability to third parties was part of a “larger movement in tort law toward encouraging risk creators to employ optimal levels of care or allocating accident costs to parties better able to bear the losses.”46 The independent audit was no longer seen as the creature of a contract, but rather as a product which, like any other product, foreseeably might harm third parties if it was defectively produced. In the various judicial pronouncements in this trend the Courts had predicted numerous benefits from the expansion of accountant liability to third parties. It was opined by the Courts that : By imposing liability on the one responsible for the loss, the foreseeability rule would cause accountants to perform more thorough audits. A more expansive liability rule would compensate the innocent third party who had relied on a defective audit. The expansion of liability was consistent with the moral blame attached to auditor misconduct. Liability expansion would promote efficient loss-spreading. The predicted benefits, however, failed to materialize. It was observed that “accountants generally have not responded to greater liability exposure by more thorough auditing but by Carl Pacini et al., “At The Interface Of Law And Accounting: An Examination Of A Trend Toward A Reduction In The Scope Of Auditor Liability To Third Parties In The Common Law Countries”, 37 Am. Bus. L.J. 171. 46 CCaappaarroo IInndduussttrriieess ppllcc vv.. D Diicckkm maann aanndd ootthheerrss 29 withdrawing audit services from high risk firms”.47 Thus, realizing the futility of this approach, many courts went on to circumscribe accountant liability to third parties. The Caparo decision has been one of the most significant in this regard and it has narrowed the scope of accountant liability to third parties for negligent misstatements. Through the instrumentality of Caparo accountant liability for negligent misstatements is now confined to cases where it can be established that the accountant knew his work product would be communicated to a non-client, either individually or as a member of a limited class, and the third party would rely on the work product in connection with a particular transaction. Sadly, with the collapse of Enron and the role of Arthur Anderson in this regard, there has been a calmour for a movement back in the direction of expansive liability of the auditors. Auditors are being sought to be made responsible to investors, creditors and others who deal with the company accounts. However, such demands are based on the misconception about the functions of the auditors. In fact there has now come into existence a wide expectation gap between what the public perceives of and expects from the auditors and the audit report and what auditors are professionally responsible for. It is submitted that the decision of the law Lords in Caparo was a step in the right direction and any movement in the opposite direction would give rise to what Cardozo referred to as liability "in an indeterminate amount for an indeterminate time to an indeterminate class". 47 Id. CCaappaarroo IInndduussttrriieess ppllcc vv.. D Diicckkm maann aanndd ootthheerrss 30 7.0. Bibliography 7.1. Articles 1. Ankit Majumdar, “Auditor’s Duty to Care”, [1998] 18 SCL (Mag.) 134. 2. Carl Pacini et al., “At The Interface Of Law And Accounting: An Examination Of A Trend Toward A Reduction In The Scope Of Auditor Liability To Third Parties In The Common Law Countries”, 37 Am. Bus. L.J. 171. 3. John G. Fleming, “The Negligent Auditor and Shareholders”, L.Q. Rev. July 1990. 4. Jon H. Holyoak, “Accountancy and Negligence”, Journal of Business Laws, 1986. 5. K. Srinivasan, “Corporate Governance- Audit as a key factor”, [2001] CLA (Mag.) 25. 6. K.R. Chandratre, “Auditors duty of care and liability for negligence: Recent Judicial Exposition”, [2002] 35 SCL (Mag.) 109. 7. P. Bhaskar Naryana, “Companies Bill, 1999: Audit and Auditors”, [2000] 26 SCL (Mag.) 47. 8. Suzanie Chua, “The Auditor’s Liability in Negligence in Respect of the Audit Report”, Journal of Business Laws, 1995. 9. Travis Morgan Dodd, “Accounting Malpractice and Contributory Negligence: Justifying Disparate Treatment Based Upon the Auditor’s Unique Role”, 80 Geo. L.J. 909. 7.2. Books 1. A. Ramaiya, Guide to Companies Act (Part II, 15th Ed., Nagpur: Wadhwa and Company, 2001). 2. A.M. Chakraboti, Taxmann’s Company Law (Vol. 1, New Delhi: Taxmann Allied Services, 1994). 3. Boyle and Birds Company Law (John Birds et. al. Eds., 3rd Ed., New Delhi: Universal Law Publications, 1997). 4. Gower’s Principles of Modern Company Law (Paul Davies Ed., 16th Ed., London: Sweet and Maxwell Limited, 1997). 5. Palmer's Company Law (Clive M. Schmitthoff Ed., 24th Ed., London: Stevens & Sons Limited, 1987). 6. S.M. Shah, Lectures on Company Law (19th Ed., Bombay: N.M. Tripathi Pvt. Ltd., 1990). 7.3. Reports 1. Cadbury Commission, Report of the Committee on the Financial Aspects of Corporate Governance (December 1992). CCaappaarroo IInndduussttrriieess ppllcc vv.. D Diicckkm maann aanndd ootthheerrss 31 7.4. Websites 1. http://www.geocities.com/orie0639/lecturenotes/hoyanoeconomicloss.htm visited on 15th May, 2002. 2. http://www.worldbank.org/html/fpd/privatesector/cg/docs/cadbury.pdf visited on 15th May, 2002.