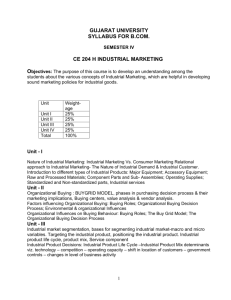

two examples of buying decision processes

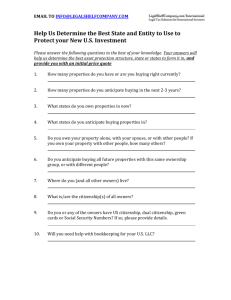

advertisement