attracting-international-students

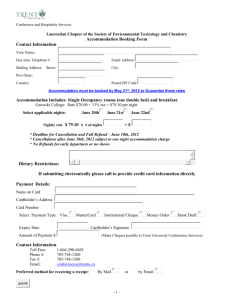

advertisement