Programming Logic & Design Textbook Excerpt

advertisement

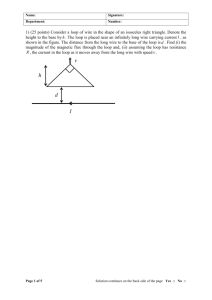

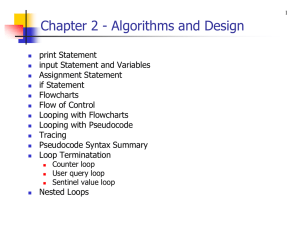

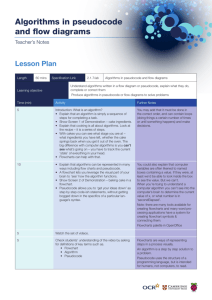

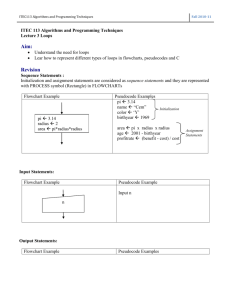

Programming Logic and Designi Preface This book can be used in a stand-alone logic course or as a companion book to an introductory programming text using any programming language. Chapter 1 introduces concepts Chapter 2 discusses key concepts of structure Chapter 3 extends the structure discussion to modules Chapter 4 creates complete structured business programs Chapter 5 explores decision-making and Boolean logic Chapter 6 discusses looping Chapter 7 introduces control breaks Chapter 8 introduces arrays Chapter 9 deals with arrays used for sorting Chapter 10 explores interactive programming using menus Chapter 11 covers matching and sequential processing Chapter 12 addresses object-oriented programming Chapter 13 addresses event-driven programming and GUI Chapter 14 addresses good programming design in terms of reducing coupling and increasing cohesion Chapter 15 provides an introduction to UML, a graphical tool for designing object-oriented systems Each chapter includes Objectives: A useful study aid Tips: Alternatives methods and terms Summaries: Recaps the programming concepts and techniques covered Exercises: Exercises increasing in difficulty designed to provide additional practice in skills and concepts Chapter One: An Overview of Computers and Logic Objectives: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. Understand components and operations Describe programming process Describe data hierarchy Understand flowchart symbols Understand pseudocode statements Use and name variables Understand sentinel variables Describe data types Key terms: Data: facts entering the computer system CPU: Hardware that organizes data, checks for accuracy, performs mathematical calculations on data Programming Language: Basic, Visual Basic, Pascal, COBOL, RPG, C#, C++, Java, Fortran Syntax: rules governing word usage and punctuation Compiler (or Interpreter): software to translate the specific programming language into the computer’s on-off circuitry language Machine Code: the computer’s on-off circuitry language Logic (of a program): the instructions given to a computer in a specific sequence Algorithm: the steps necessary to solve any problem Conversion: the entire set of actions an organization must take to switch over to using a new program Flowcharts: pictorial representation of the logical steps it takes to solve a problem Pseudocode: an English-like representation of the steps it takes to solve a problem Variables: memory locations whose contents can vary or differ over time Decision: testing a value Dummy Variable: pre-selected value that stops execution of a program EOF: end of file (of data) Constants: named memory location, the value of which never changes during a program (numeric or string) Computer System Components 1. Hardware: equipment or devices associated with a computer 2. Software: instructions that tell the computer what to do Major Operations 1. 2. 3. 4. Input Processing Output Storage Every computer operates on circuitry that consists of millions of on-off switches The compiler or interpreter tells you if you have used a programming language incorrectly For a program to work correctly, you must not leave any instructions out or add extraneous instructions Logic errors are much more difficult to locate than syntax errors Once instructions have been input to the computer and translated to machine language, a program can be run or executed. Computers often have several input devices such as a keyboard, a mouse, a CD drive or a disk drive Disk and CD drives are often categorized as storage rather than input devices Storage 1) Internal storage a) Memory i) Main memory / primary memory 2) External storage a) Floppy disk b) Hard drive c) Magnetic tape Internal memory is volatile, i.e. contents are lost every time the computer loses power External storage is permanent, i.e. non-volatile storage Computer memory consists of millions of numbered locations where data can be stored Programming Steps 1) 2) 3) 4) 5) 6) 7) 8) Understand the problem Plan the logic – developing an algorithm Code the program Translate the program into machine language Test the program Put the program into production Maintaining a program Retiring a program Understanding the problem may be one of the most difficult aspects of programming: The description of what the user needs may be vague User may not know what it is he or she wants Planning the logic entails deciding on the steps to include and how to order them Utilizes flowcharts or pseudo-code Is more difficult than coding the program Compilers and interpreters translate high-level languages into low-level languages, i.e. machine language A program that is free of syntax errors is not necessarily free of logical errors Programs should be tested with many sets of data Many companies don’t know that their software has a problem until an unusual circumstance occurs Maintenance is necessary for a number of reasons 1) Changes in the environment 2) Changes in specifications 3) Formats of input change 4) Errors are found Data Hierarchy Bits Bytes Characters – smallest usable unit of data Fields – a single data item Records – logical groupings of fields Files – logical grouping of records Tables – groups of files that together serve the needs an organization Databases – organized groupings of files in table form Using pseudocode is similar to writing final statements in a programming language Flowcharts allow a programmer to more easily visualize how the program statements will connect Programmers seldom create both pseudocode and a flowchart for the same program Almost every program involves the steps of input, processing and output When you crate a flowchart, you draw geometric shapes around the individual statements and connect them with arrows A parallelogram represents input A rectangle represents processing, i.e. such as performing arithmetical calculations Parallelograms are also used for output A terminal or start/stop symbol is used at each end A diamond is used as a decision symbol is used for branching A connector is often used on longer flowcharts Looping will allow a program to do repetitive calculations It is the ability of memory variables to change in value that makes computers and programming worthwhile Because one memory location can be used over and over again with different values, you can write program instructions once and then use them for thousands of separate calculations Most languages allow both letters and digits within variable names Different languages put different limits on the length of variable names Newer languages tend to be case-sensitive Most languages use camel casing where multiple words are run together with each new word being capitalized Variable naming rules (for this book) Must be one word Names should have some appropriate meaning Variable names may not begin with a digit All good computer questions have two mutually exclusive answers like yes or no or true or false Sentinel values represent an entry or exit point for a program Programming languages can recognize the end of data in file automatically without using a sentinel value through a code that is stored at the end of the data. Connectors should contain a letter or number that can be matched with another location Avoid using connectors whenever possible. Most computer languages allow a shorthand expression for assignment statements that give variables values Whatever operation is performed to the right of the equal sign results in the value that is placed in the memory location named to the left of the equal sign It might help to imagine the word “let” in front of an assignment statement It makes no sense to perform mathematical operations on memory locations, but it does make sense to perform them on the contents of memory locations Many programming languages allow you to create constants Some languages require single quotes surrounding character constants while others require double quotes. Programmers must distinguish between numeric and character variables because computers handle the two types of data differently, i.e. you cannot perform numeric calculations on string data. Finer distinctions may exist in some languages, such as those between integer and floating-point variables Literals are generally represented between quotation marks to distinguish them from variable names Summary 1) Together, hardware and software accomplish input, processing, output, and storage. 2) A programmer’s job involves understanding the problem, planning the logic, coding the program, translating the program into machine language, testing the program and putting the program into production 3) Data is stored in a hierarchy of characters, fields, records, and files 4) Pseudocode and flowcharts are used to plan logic 5) Variables are named memory locations. All variable names must be written as one word without embedded spaces and should mean something 6) Testing a value means making a decision. All computer decisions include discreet values 7) Most languages allow the equal sign to assign values to variables. Assignment always takes place from right to left 8) Programmers must distinguish between numeric and character variables Chapter Two: Understanding Structure Objectives: 1) 2) 3) 4) Understand what makes spaghetti code Describe three basic structures making up structured programs Understand primary reads Recognize structure Key terms: Spaghetti Code: snarled program statements due to lack of structure Unstructured code results in programs that may work, but are very difficult to read, with logic that is difficult to follow Understanding the Three Basic Structures 1) Sequence – performing an action and then the next action in order 2) Selection – ask a question and depending on the answer, you take one of two courses of action. No matter which path you follow, you continue on with the next event. 3) Looping – you ask a question; if he answer requires an action, you perform the action and ask the original question again. This continues until the answer to the questions is such that the action is no longer required. Any program, no matter how complicated, can be constructed using only three sets of flowcharting shapes or structures; each basic unit of programming logic is a sequence, a selection or a loop Selection is called the if-then-else structure A single alternative if structure also exists. The case where nothing is done on a branch is called the null case. Looping represents repetition or iteration. The three basic structures can be combined in an infinite number of ways. Attaching structures end-to-end is called stacking Placing a structure within another structure is called nesting Aligning steps vertically in pseudocode shows that they are “on the same level” Dependent steps are indented, showing they are “one level down” In pseudocode, ENDIF always partners with the most recent IF Each structure has only one entry and one exit point Structured Programs 1) Includes only three types of structures 2) Structures connect to one another only at their entrance or exit points 3) With a sequence, each step must follow without any opportunity to branch away a) Sequences never have decisions in them 4) With a selection, logic goes in one of two directions after the question; then the flow comes back together a) The question is not asked a second time 5) In a loop, if the question result in the procedure executing, then the logic returns to the question that started the loop a) The question is always asked again b) The loop must go back directly to the question to be considered structured i) The last step executed in the loop alters the condition tested in the question that begins the loop, e.g. EOF For a program to be structured and also work the way you want it to, sometimes you need to add extra steps 1) The priming read (or priming input) is one kind of added step a) Read in a separate statement b) Purpose is to control the upcoming loop Reasons for Structure 1) 2) 3) 4) 5) Clarity Professionalism Efficiency Maintenance Modularity When analyzing a flowchart, if a line is attached somewhere else, untangle it by repeating the step that is tangled Two Special Structures: Case and Do-Until You can solve any logic problem with the sequencing, selection, and looping Many languages allow two more structures: 1) Case structure a) Test a variable against a series of values, taking appropriate action based upon the variable’s value b) Easier to read c) A convenience, the computer still makes a series of individual decisions 2) Do-until a) In a DO-WHILE, you may never enter the loop b) A DO-UNTIL ensures that procedures execute at least once c) You can create the same sequence generated by a DO-UNTIL loop by creating a sequence followed by a DO-WHILE loop Summary 1) Clearer programs can be constructed using sequences, selections and loops connected in an infinite number of ways a) Each structure has one entry and one exit point 2) A priming read is the step prior to beginning a structured loop a) The last step in the loop gets the next and all subsequent input values 3) You can use a case structure when here are several distinct possible values for a variable you are testing; the computer continues to treat them as individual decisions 4) A DO-UNTIL ensures that procedures execute at least once Chapter Three: Modules, Hierarchy Charts and Documentation Chapter Four: Writing a Complete Program Chapter Five: Making Decisions Chapter Six: Looping Chapter Seven: Control Breaks Chapter Eight: Arrays Chapter Nine: Advanced Array Manipulation Chapter Ten: Using Menus and Validating Input Chapter Eleven: Sequential File Merging, Matching and Updating Chapter Twelve: Advanced Modularization Techniques and Object Oriented Programming Chapter Thirteen: Programming Graphical User Interfaces Chapter Fourteen: Program Design Chapter Fifteen: System Modeling with UML Appendix A: A Difficult Structuring Problem Appendix B: Using a Large Decision Table Index Farrell, Joyce. “Programming Logic and Design”, Comprehensive Second Edition, Copyright 2002: Course Technology, a division of Thompson Learning. i