Introduction - Berrymans Lace Mawer

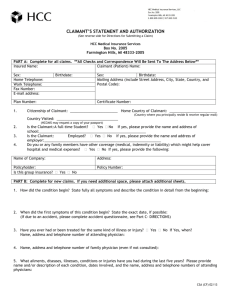

advertisement