Examination of Catcher in the Rye

advertisement

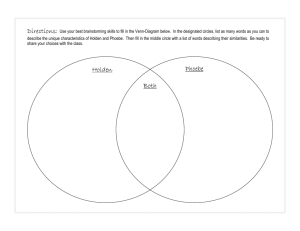

An Examination of J.D. Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye The isolation that was prevalent in JD Salinger’s life was brutally exposed in Catcher in the Rye; not only shaping the central theme and underlying motifs, but was most strikingly portrayed through the protagonist, Holden Caulfield. His writing is unique and energetic; often drawing upon Salinger’s own feelings of inadequacy as a youth. Realism, vivid imagery and intricately honest dialogue allow young people to relate to his work on an intimate level. Salinger has his own language, molded out of his own life experiences, religious beliefs and outlook on society in general; it was a language that was devoured by his critics, his followers and by the society that he yearned to escape from. Salinger uses Holden Caulfield, a virtual mirror of himself as a youth to narrate the Catcher in the Rye. Like Salinger, Holden attended a “fancy” preparatory school; and like Salinger, Holden was asked to leave the school. They were both raised in New York by wealthy parents. Holden is renowned for his disconnection from society, and in particular, from the adult world. In Catcher in the Rye he is often seen standing alone, or is escaping conversations by lying or insulting someone. Even as he was leaving the school for good, Holden was unable to connect with the other students: When I was all set to go, when I had my bags and all, I stood for a while next to the stairs and took a last look down that goddam corridor. I was sort of crying. I don't know why. I put my red hunting hat on, and turned the peak around to the back, the way I liked it, and then I yelled at the top of my goddam voice, "Sleep tight, ya morons!" I'll bet I woke up every bastard on the whole floor. Then I got the hell out… (J. Salinger 52) Similarly as an adolescent Salinger often felt disconnected from his peers and he considered himself an outsider although to others he appeared to fit in (Bloom in J.D Salinger 11). The detachment he suffered was made worse by having to grow up in a world shrouded in anti-Semitism; for example, he attended Valley Forge Military School, which was in an area of Pennsylvania that the US army War Board rated as the heart of anti- Semitism in America. Although his grades improved while at the military school, many colleges at that time would not consider admitting a student who was of the Jewish descent, lending to his feelings of disgust at what he called “Ivy League snobbery” (Bloom in J.D. Salinger 10). His distain for the latter is seen throughout The Catcher in the Rye and is referred to within the very first few pages of the book. “Quite a few guys came from these very wealthy families, but it was full of crooks anyway. The more expensive a school is, the more crooks it has—I’m not kidding” (J. Salinger 4). Holden is letting the reader know how he feels about the students who attend Pencey Prep with him. Even outside of the academic atmosphere Holden belittles the Ivy Leaguers: “The worst part was, the jerk had one of those very phony, Ivy League voices, one of those very tired, snobby voices. He sounded just like a girl” (J. Salinger 128). While Holden is eavesdropping on conversations at Ernie’s he is bothered: “On my right there was this very Joe Yale-looking guy, in a grey flannel suit and one of those flitty-looking Tattersall vests. All those Ivy League bastards look alike. My father wants me to go to Yale, or maybe Princeton, but I swear, I wouldn’t go to one of those Ivy League colleges, if I was dying, for God’s sake” (J. Salinger 85). He also refers to the phoniness of the school in his description of the Pencey “propaganda”: “They advertise in about a thousand magazines, always showing some hotshot guy on a horse jumping over a fence. Like as if all you ever did at Pencey was play polo all the time. I never even once seen a horse anywhere near that place,” (J. Salinger 2). Holden is Salinger’s mouthpiece; in fact, he told an acquaintance by the name of Shirlie Blaney: “I was very much relieved when I finished [the novel]. My boyhood was very much the same as that of the boy in the book and it was a great relief telling people about it” (Alexander 177-178). Later, during a small stint at Ursinus College, he was also remembered for his solitude. A fellow student: “I do remember him and I remember him because it is my impression that he was not close to anyone- students or professors. Indeed my recollection is he was pretty much of a loner” (Bloom in J.D. Salinger 13). Isolation permeated most aspects of Salinger’s life both during adolescence and adulthood; he eventually came to embrace the philosophies of Zen Buddhism, further shaping not only his own introversion, but adding depth and vividness to the stark language of his writing. One of the basic tenets of Zen Buddhism is the relinquishment of “illusions” (Rosen 1). This belief along with the alienation and detachment which resided in Salinger molded his portrayal of the protagonist Holden Caulfield. In Catcher in the Rye the very first place that the reader sees Holden is standing atop a hill detached from everyone else: … I remember around three o’clock that afternoon I was standing way the hell up on top of Thomson Hill, right next to this crazy cannon that was in the Revolutionary War and all. You could see the whole field there, and you could see the two teams bashing each other all over the place. You couldn’t see the grandstand too hot, but you could hear them all yelling, deep and terrific on the Pencey side, because practically the whole school except me was there… (J. Salinger 2). Not only is Holden separated from “practically the whole school,” he is looking down on them with an air of superiority while standing next to a lone cannon. Holden’s alienation is one of the novel’s primary motifs, recurring both constantly and obviously. He separates himself from the masses internally by having a consistent air of superiority and externally by using things to differentiate himself, such as his symbolic Red Hunting Hat. The hat shows both his need to be different and his yearning to be accepted. Holden wears the hat it to be unique and stand out in a crowd, he often refers to the “outlandish” nature of the hat, yet he takes it off around people he actually knows in order to fit in and not be stared at. This duality is a recurring motif throughout The Catcher in the Rye. Holden is contradiction personified: he says he is an Atheist, yet talks about Allie being in Heaven; he says, “I’m quite illiterate, but I read a lot,” (J.Salinger 15); Holden believes most people to be phony, yet is a self- proclaimed liar. Like the Zen Buddhists, Holden uses detachment as a form of protection from the outside world, which they both perceive as rife with illusion or as Holden would say, “phoniness.” Paradoxically, his need for isolation tends to be the cause of the majority of his problems. For example: he decides to date a girl named Sally Hayes because he is lonely; however he insulted her until she finally rejected him, allowing him to escape back into the safety of his own isolation. Similarly, Salinger himself, who embraced isolation, wrote a novel that instantly became both famous and infamous, propelling him into the center of controversy and acclaim. He, like Holden, escaped into safety and became increasingly more reclusive and withdrawn. The central theme of Catcher in the Rye is the feeling of loneliness, pain and angst related to having to grow up. Holden’s greatest dilemma is the protection of the innocence of childhood. This he makes perfectly clear through the depiction of his fantasy of being the “Catcher in the Rye” and saving the innocents from death: “…I keep picturing all those little kids playing some game in this big field of rye and all. Thousands of little kids, and nobody’s around- nobody big, I mean, except me. And I’m standing on the edge of some crazy cliff. What I have to do, I have to catch everybody if they start to go over the cliff…” (J. Salinger 173). Holden has deemed himself protector of the droves of innocent children and in the book the only people that he actually admires are those that represent his pure ideals, such as his younger sister Phoebe. He read through Phoebe’s entire notebook and said: “…I can read that kind of stuff, some kid’s notebook, Phoebe’s or anybody’s, all day and all night long. Kid’s notebooks kill me” (J. Salinger 161). To Holden the notebook represented childish naivety in the form of scribbling and random thoughts. He affectionately refers to Phoebe as “old” Phoebe several times, outwardly expressing the fondness and warmth that he feels toward her. Whenever Holden sees something as being the antithesis to this innocence he becomes depressed and anxiety ridden. While wandering in New York he comes across a few places where the words “fuck you” were written on walls. After seeing the words scrawled on a wall for the second time in a short period he seemed to suffer an actual panic attack characterized by a sudden onset of diarrhea and a fainting spell. He was afraid that children would come across the graffiti and that would add to the deterioration of their virtuousness. Interestingly, in Salinger actually writing the words “fuck you” in a novel at the time in which The Catcher in the Rye was published caused the book to be deemed “dirty” and to be banned to protect the innocence of the droves of school children who might read it. Harold Bloom put it best when he said, “Salinger here is not playing Catcher at all, but is asking the reader to grow up and accept the fallen world in which he finds himself” (Rosen 10). Conversely, he views the adult world as phony and full of imposters. There are countless references to the phoniness of adults and to the fact that they can’t even help being phony; it’s just an inherent quality of being of the adult world. Holden is so enraptured with the idea of phoniness that he even refers to certain words as phony: “Grand, if there’s one word I hate, it’s grand. It’s so phony” (J. Salinger 106). Holden hates movies because he feels that they are phony exaggerations of life, yet he seems to watch a lot of them, once again lending to the thought that Holden is a big phony. Salinger himself experienced this phoniness when he found out that his mother, whom he always believed was Jewish, was actually Catholic (M. Salinger 30). One of the fundamental beliefs of Zen Buddhists is “I will honor honesty and truth; I will not deceive” (Nagamoto 117). Ironically, another one of the most obvious motifs is that of lying and deception. Although disappointed with the aforementioned phoniness of the adult world, Holden lets the reader know up front what a liar he is: “I’m the most terrific liar you ever saw in your life” (J. Salinger 16). In letting the reader know that Holden is a liar, Salinger is telling us not to trust him as a narrator. The book is saturated with the motifs of lying and deception; and loneliness and isolation; but one of the most prevalent motifs is that of compassion. Salinger delves further into the confusion of youth coming of age by showing a Holden that is both constantly lying and feeling sorry for people. “Sympathetic Empathy” is a beloved expression of Zen Buddhists, and refers to “…that remarkable mixture of coarseness and unlimited compassion that the masters, each in his own style, embody” (Dumoulin 131). Salinger has certainly bestowed both of these qualities upon Holden. He goes as far as to have felt sympathy for an instructor at the school because the instructor was forced to flunk him. He felt sorry for the headmaster’s daughter because of her physical appearance. He felt sorry for the children who may be exposed to the vulgarity he tries so hard to erase. He felt sorry for Ernie’s mother because according to Holden, “Her son was doubtless the biggest bastard that ever went to Pencey, in the whole crumby history of the school” (J. Salinger 54). He then proceeded to tell Ernie’s mother what a great and popular student Ernie is, in order to protect her feelings. In fact a lot of his lies were because he felt sorry for people and wanted to protect them. The entire style in which the book was written seems to endeavor to exclude the adult world. The story is told via Holden, in his own unique seventeen year old language and from his extremely narrow outlook of the world. Salinger’s words are vivid and energetic, allowing young people to relate to the work on a familiar level. Holden, like some teenagers, lies to almost everyone he meets; however, he is brutally honest when it comes to his descriptions of loneliness and his feelings about the world when he is speaking to the reader. In using the first person, Salinger only allows the reader to see events through the eyes of Holden, with his limited world view and his self- proclaimed dishonesty; this leaves room for incredible amounts of interpretations and criticisms (Bloom in Catcher 43). “Life is suffering” is one of the most well known “Noble Truths” in Buddhism and almost all aspects of this book are enveloped in this sentiment. Salinger and Holden both lived lives filled with suffering; the former taking refuge in isolating himself from the society he so detested and the latter ultimately being forced into a mental institution, guaranteeing himself isolation from that same society. That Noble Truth is intrinsically weaved into Salinger’s writing style which is one of the reasons that the Catcher in the Rye became so beloved amongst teens; it was a mantra that they seemed to live by. Aside from that emotional connection, Salinger used literal techniques to make Holden more realistic. He had Holden speak directly to the reader and gave him little habits and idiosyncrasies in his speech; he had a personality and unique way of communicating. Statements often end with “and all” as in “… it was in the Revolutionary War and all,” or “…it was December and all” (J. Salinger 2- 4). Holden tends to try to let the reader know that he is telling the truth by repeating himself (Cooper 1), for example: “She likes me a lot. I mean she’s quite fond of me” or “”He was a nervous guy—I mean a very nervous guy” (J. Salinger 144-165). Holden knows that he is a liar, and has actually let the reader know that that he’s a liar so he tries to reiterate certain thoughts to assure the reader that he is indeed telling the truth at that moment. Another interesting idiosyncrasy of Holden’s is to generalize the masses with his constant usage of the word people; in fact, it is the start to some of the most famous lines from Catcher in the Rye. “People never notice anything.” “People always think something’s all true.” “This is a people shooting hat…I shoot people in this hat.” “Take most people, they’re crazy about cars.” and “People never give your message to anybody” (J. Salinger 9-22-130-131). Holden refers to others as a uniform body to which he does not belong; and in his generalization he not only separates himself from them, he elevates himself above them. In giving Holden grammatical habits, Salinger forces the reader to see him as an actual person, an actual teenage person. Holden possesses a unique vernacular that is rife with slang and profanity. He speaks to the reader in a stream of consciousness style, saying exactly what is going through his mind at that given moment. Teenagers found the style not only easy to relate to, but highly understandable. There were no complex thought patterns or vocabulary that would hold you back from interpreting the simple flow of thought from Holden. “Many critics have likened the vernacular in Catcher in the Rye to Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn; not only as a valuable literary work, but as a valuable study in dialect,” (Costello 11). Holden lives by one of the famous saying of Buddha, “The greatest source of suffering is the belief in a single, continuous, unchanging personality, and the attempt to hold onto it” (Rosen 2). Holden is unwilling and unable to let go of a multitude of things including objects, such as Allie’s glove or the broken pieces of Phoebe’s record; however, he is most guilty of holding onto his ideas and images of the world (Rosen 9). He hangs on to his childish outlook and is stuck in the “in-between” of youth and phony adulthood. As Holden latched on to Phoebe as his ideal of youthful purity, many would say the same of Salinger, who seemed to surround himself by young people, eventually marrying a woman thirty years his junior. The young woman was named Joyce Maynard, who Salinger’s daughter Peggy described as: “…perfectly nice and everything, but who expects to find someone looking like a twelve year old year girl” (Bloom in J.D. Salinger 37). Salinger warned Maynard to beware the “establishment” that would eventually try to corrupt her, once again trying to keep her in the state of innocence and wholesomeness that he so desired. He went so far as to give her an ultimatum: a degree from Yale University (one of the Ivy Leagues that he had Holden so vehemently denounce), or Salinger. Like Holden, Salinger’s reclusiveness may have been due to his inadequacies and distrust of society in general; Catcher in the Rye illuminated these sides of Salinger and he used Holden Caulfield as an implement in the telling of his own story. Many say Salinger shaped a generation with Catcher in the Rye, and although it was banned and assailed by a multitude of institutions, it was also embraced by scores of youth who felt an undeniable connection with Holden. Salinger turned the character of Holden Caulfield into a “real” person and his readers both devoured and imitated the words of Holden. Ironically, the isolation and alienation that resounded in the novel ended up uniting that entire generation of teens who once felt like they had no place “to fit in.” Works Cited Alexander, Paul. Salinger: a Biography. Los Angeles: Renaissance, 1999. Print. Bloom, Harold. J. D. Salinger. Philadelphia, PA: Chelsea House, 2001. Print. Bloom, Harold. J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye. Philadelphia: Chelsea House, 2000. Print. Cooper, Michael. “Use of language in The Catcher in the Rye - Salinger - Literature.” EzineArticles. 2010. Web. 01 Nov. 2010. <http://ezinearticles.com/?Use-ofLanguage-in-The-Catcher-in-the-Rye---Salinger---Literature&id=90692>. Dumoulin, Heinrich, James W. Heisig, and Paul F. Knitter. Zen Buddhism, a History: Volume 2, Japan. New York: Macmillan, 1990. Print. Laser, Marvin, and Norman Fruman. Studies in Jd Salinger. New York: Odyssey, 1963. Print. Nagatomo, Shigenori. “Japanese Zen Buddhist Philosophy (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy).” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 28 June 2006. Web. 07 Dec. 2010. <http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/japanese-zen/>. Rosen, Gerald and Harold Bloom. “A Retrospective Look at Catcher in the Rye.” Blooms Modern Critical Views: J.D. Salinger (1987): 95-109. Literary ReferenceCenter. EBSCO. Web. 26 Oct. 2010 Salinger, J.D. The Catcher in the Rye. Boston: Little, Brown, 1951. Print. Salinger, Margaret Ann. Dream Catcher: a Memoir. New York: Washington Square, 2000. Print.