Ching

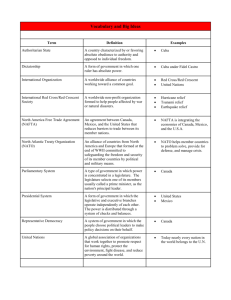

advertisement

Business cycle synchronization between U.S. and Mexico manufacturing industries By: Christopher Ching Abstract: This paper provides evidence of stronger industrial production synchronization between Mexico and The United States after the enactment of NAFTA, particularly due to supply-links. The determinant of the supply-link will ultimately prove to be the increase in intermediate imports to Mexico from the U.S… Before diving into intermediate goods other factors are considered and tested. Previous historical data is also reviewed suggesting that Maquiladoras are similar to FDI after NAFTA. Although the conclusion is obvious, there is still much analysis of the situation in other perspectives. This will help to gain an understanding for my final conclusion. The North American Free Trade Agreement came into effect on January 1st 1994. It helped to eliminate tariffs and investment regulations between the U.S, Mexico, and Canada. By eliminating most tariffs and regulations we would expect to see an increase in trade and foreign direct investment. Prior to NAFTA, trade liberalization had occurred but on a much smaller scale. In 1947 Mexico had a closed economy, and it wasn’t until the mid 1960’s that Mexico had let up on its trade barriers and regulations. It was the duty free Maquiladoras that started it all. Almost like a preview of the future except on a smaller scale. Maquiladoras are duty free foreign owned shop floors, but are limited to a twenty-kilometer radius from the border. Mexico intermediate goods from the U.S. are tariff free. Those goods are then assembled using Mexican labor and are re-exported back to the U.S. duty free. What this essentially allowed was bilateral trading in its most early stages. At this time the use of Mexican labor was controversial to both the U.S. and Mexican parties, but that is a topic to be discussed later. What is important to understand is that before NAFTA was enacted there was prior trade liberalization and FDI. Manufacturing sectors didn’t start to appear in Mexico until the 1980’s. So it would only make sense to collect data from the 1980’s and on, considering that I’m looking at industrial production synchronization. In 1986 Mexico joined the General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs; Mexico was officially an open economy. Before determining the causes of industrial production synchronization we must classify what synchronization is, and at what point is there synchronization and nonsynchronization. The case between the U.S. and Mexico is special because of the comparing economy sizes and development stages. At almost any point of time between 1980 and the present, the U.S. has dwarfed Mexico’s economy relative to GDP. The U.S. has always been the developed country and Mexico the developing country. We must understand that any affect Mexico has on the U.S. is minimal in a sense that it won’t drastically alter the course of U.S. business cycles. This is not the same the other way around. Depending on the point in time and severity of the situation, the U.S. has the GDP size to drastically alter Mexico’s business cycles. It all depends on the situation at hand. There have been times in the past were Mexico has created its own turmoil. If you look at figure 1 we can see in the year that NAFTA was enacted (1994) there was a huge drop in Mexico’s industrial production GDP. The main cause of this recession was the peso crisis. The devaluation of the peso discouraged imports into Mexico, and in theory Mexico depends on imports to add value to then re-export later. If there was no peso crisis of 1994 we possibly would have seen a correlation with U.S. industrial production. Never the less Mexico’s individual economic situations can disrupt their own business cycles and have little or no effect on U.S. business cycles. The question still remains, were do we draw the line for synchronization and nonsynchronization? Looking at figure 2 we see a time series of percent changes for Mexico and U.S. industrial production. The more similar the IP percent changes are for each year the more synchronized there business cycles will be. From 1989-1995 there is less visible correlation than usual. The most probable explanation for this is Mexican economic turmoil that is not connected to the U.S., Like the Peso Crisis. Being able subtract these types of situation from the data is hard maybe impossible, but would give us a better idea of how NAFTA truly affected U.S.-Mexico synchronization. In the early 1980’s just by looking at figure 2 we can see a lagged synchronization. This is not true synchronization, but there is an obvious connection between the two countries. Most likely demand related. After 1995 there are truer forms of synchronization, both correlating on time. To be more specific if you look at table 3 and 4, differences in percentage changes can give better perspectives on synchronization. Basically the lower the trend line remains on the graph the greater the synchronization. In the early 1980’s of lagged synchronization the trend line is high; therefore we consider this to be a time of non-synchronization. And after the peso crisis of 1994 the trend line remains low. We will draw the line of synchronization at any percentage difference less than or equal to 2, and anything above 2 is non-synchronized or unsynchronized. Now that the line is drawn at what we consider to be synchronization and nonsynchronization, we conclude that after NAFTA was enacted in 1994, there is synchronization. We will take the peso crisis into consideration, and assume that without it we would see synchronization. Within the NAFTA agreement there was obviously a factor that triggered IP synchronization. To determine what and what are not factors that created IP synchronization let’s start by looking at figure 5. U.S. imports and exports with Mexico as a percent of their world trade is relatively low. We can immediately state from 1993 to 2001, U.S. trade with Mexico is too small for the U.S. to be connected to Mexico. This data proves the U.S. economy is not strongly linked to the Mexican economy. In figure 6,7,8 Mexico trade with the US relative to Mexico’s trade with the world is given. Figure 7 shows the value of world trade compared to the value of U.S. trade. The positively sloping lines are correlated and close together. Meaning that the majority of Mexico exports go to the U.S... More specifically in figure 8 the percent of exports to the U.S. compared to world exports has risen to stay above 80% after 1993. This data is meaningful because it shows Mexico’s connectivity with the U.S., but also after NAFTA exports did increase. Data does show a correlation between synchronization and Mexico exports to the U.S., but that does not mean Mexico exports are the direct cause of synchronization. This upholds the demand side of the situation. With only a demand side we would expect lags in synchronization. Going back to figure 2, on the left side demand lags are visible. For example; if U.S. consumers are importing calculators from Mexico, Mexico’s calculator business cycles will be dependent on how many calculators are sold to U.S. customers over time. If U.S. customers stop buying calculators because currently they are in a recession and consuming less, than Mexico is going to have a surplus of calculators and eventually fall into a recession. The timing will be lagged because of unpredictable U.S. market conditions by Mexico, and the calculator market not stopping production until after the U.S. has fallen into a recession. This scenario is possible only if Mexico was getting there calculator materials from either their own country or another country and not through U.S. FDI. I say FDI because if Mexico was importing goods through the U.S. and paying for it with peso’s then high U.S. inflation would mean a better exchange rate for Mexico, but with FDI the peso exchange rate would only affect the cost of labor and rent. U.S. FDI in Mexico who are paying with Dollars are immediately affected by the recession and will supply less to Mexico from the U.S. and slow down the production process immediately. Remember that before NAFTA was enacted in 1994 there was U.S. owned Maquiladoras, but most likely a smaller amount than post NAFTA. NAFTA increased foreign direct investment by taking away from exchange rate differences and therefore demand lags. Looking at the supply of intermediate goods (figure 9), imports from the U.S. to Mexico has risen consistently from the beginning of the 1990’s. This could be because of investor forecasting. Nevertheless, as the amount of intermediate goods increases we can expect to see an increase in IP synchronization, because now there is a supply-link. U.S. FDI in Mexico will import intermediate goods from the U.S. for production processing, than those products will be re-exported to the U.S. for final sale. This is called vertical trade or intra-industry. Figure 10 shows the correlation between intermediate imports from the U.S. and total U.S. exports from Mexico to the U.S… This graph is highly correlated after the enactment of NAFTA in 1994, and suggests that Mexico exports are highly dependent on intermediate imports from the U.S… Figure 11 shows the relationship between synchronization and intermediate imports from the U.S… What is important to understand here is that as intermediate imports increase, IP synchronization gets stronger. The graph suggests a negative relationship, because of the fall of the synchronization trend line, but it is actually a positive relationship. Before making a final conclusion that intermediate goods create a stronger IP synchronization lets look at some statistics. Similar to figure 3 and 4 I took the annual percentage differences from IP indexes, which was previously monthly data. I named that to be the dependent variable. Next I took intermediate imports to Mexico from the U.S. and divided it by Mexico GDP adjusted with the exchange rate. This is my independent variable. Dependent variable= |Mexico IP index percentage change-United States IP index percentage change| Independent variable= intermediate imports to Mexico from U.S./GDP Mexico adjusted to dollar exchange rates With this I came up with figure 12. The t-statistic is greater then 1.97, which implies only a 5% chance of error. The coefficient is 20, which tells a great deal about the intermediate-synchronization relationship. This means that for every 1% increase in the intermediate goods to Mexico GDP ratio, there will be a 20% stronger synchronization in percentage differences. The data and evidence collected suggests that NAFTA’s creation of free trade has helped to synchronize U.S. and Mexico IP business cycles. Free trade has made it more efficient to run intra-industry markets and in turn has created more FDI then before. With the increase of FDI, exchange rate differences are of little relevance to the disrupting of synchronization with the exception of labor, rent, and utility costs (electricity, water…etc). Previous Maquiladoras were limited in numbers and small compared to the amount of U.S. FDI after NAFTA. Intermediate goods are the main determinant of IP synchronization. Figure 11 helps to support this statement, showing the positive relationship of intermediate goods to IP index percentage differences. As intermediate goods increase, IP index percentage difference grows smaller. The coefficient of determination with a T-statistic greater then 1.97 is 20. This high coefficient of 20 is large enough to conclude that an increase in intermediate goods as a result of NAFTA is strengthening synchronization. Figure 1 Figure 2 Figure 3 Figure 4 Figure 5 Percent of U.S. exports and imports going to Mexico Time 1980’s Right before NAFTA (1993) 2001 Exports to Mexico (1982) 3.7% (1993) 8.8% (2001) 14.2% Imports from Mexico (1986) 4.6% (1993) 7.1% (2001) 11.8% Figure 6 Years 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 total exports total exports to U.S. 20532 20409 23046 27167 26939 27166 51760 60882 79541 96000 110431 117494 136391 166199 158899 161235 164892 187812 13265 13454 16163 18837 18729 18657 43117 51943 66475 80673 94531 103306 120393 147400 140564 141898 144293 164522 Figure 7 % exported to US 64% 65% 70% 69% 69% 68% 83% 85% 83% 84% 85% 87% 88% 88% 88% 88% 87% 87% Figure 8 Figure 9 Figure 10 Figure 11 Figure 12 1981-2006 b coeff sb,sa R2,Sy F,df ssr,sse t-stat References: 20.63301557 6.899327409 0.271481958 8.943590416 70.76960345 2.990583625 a 6.92155004 1.199985563 2.812985089 24 189.9092427 5.768027759 “International monetary Fund,” www.imf.org “Instituto Nacional De Estadisticia Geografia E Informacia,” www.inegi.org.mx “The bank of Mexico,” www.banxico.org.mx “The Federal Reserve,” www.federalreserve.gov Articles: U.S.-Mexico Trade: are we still connected? Maquiladora industry: past, present and future Maquiladora downturn: structural change or cyclical factors? The nature and signifigance of Intra-industry trade Did NAFTA spur texas exports? U.S., Mexico deepen economic ties Daniel Chiquiar, Manual ramos-Francia, “Bilateral Trade and Business cycle Synchronization evidence from Mexico and the United States manufacturing industries,” 2004-2005.