File

advertisement

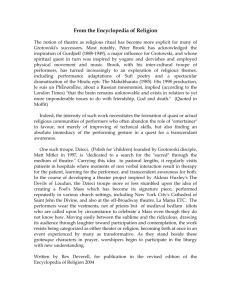

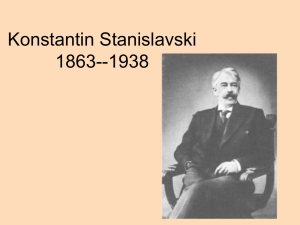

Jerzy Grotowski (1933 to 1999) Poor Theatre Grotowski is unique. Why? Because no one else in the world, to my knowledge, no one since Stanislavski,has investigated the nature of acting, its phenomenon, its meaning, the nature and science of its mental, physical, emotional process as deeply and completely as Grotowski. Peter Brook”s introduction to Grotowski’s book “Towards Poor Theatre” Grotowski set out to ask one question only: What is theatre? In his serarch for an answer he found that while theatre could exist without make-up, costume, décor, a stage, lighting, sound effects, it could not exist without the relationship of actor and spectator. This essential act, this encounter between two groups of people, he called “Poor Theatre”. He was committed to experimentation and in 1965 he established the Laboratory Theatre in Wroclaw. This officially became an Institute for Theatre Research with each production becoming a working model of current research. For Grotowski, the actor is a high priest who creates the dramatic liturgy and, at the same time, guides the audience into the experience. Here, then, is a new element in the theatre: a psychological tension between actor and audience. The purpose of theatre, indeed, of all art, is “to cross our frontiers, exceed our limitations, fill our emptiness – fulfil ourselves”. To this end the actor must learn to us his role as if it were a surgeon’s scalpel to dissect himself. “The important thing is to use the role as a trampoline, an instrument with which to study what is hidden behind our day mask – the innermost core of personality – in order to sacrifice it, expose it.” The spectator, says Grotowski, understand, consciously or unconsciously, that such an act is an invitation to him to do the same thing. This often arouses opposition or indignation because our daily efforts are intended to hide the truth about ourselves not only from the world but from ourselves. Grotowski is not concerned with taking the spectator out of himself, in the escapist manner of the naturalistic or romantic theatre, but with taking him deeply into himself. His concern is with the spectator who has genuine spiritual needs and who really wishes, through confrontation with the performance, to analyse himself. It is his preoccupation with the role of the spectator in theatre that has led him to explore the nature of scenic space, creating a form of staging for each production that would test different aspects of the relationship between actor and spectator. In Kordian the action was set in a psychiatric ward. The entire space was filled up with beds so that the spectators found themselves having to sit among the sick. In Dr.Faustus the spectators found that they were, along with the actors, guests at Dr. Faustus’s table in the monk’s refectory. In Akropolis (a classic Polish play in which statues and paintings in a cathedral come to life and re-enact various biblical and Homeric themes), Grotowski moved the action to Auschwitz in order to test how far the classical idea of human dignity can withstand our latest insight into human degradation. The production was set on a large rectangular stage set in the centre of the audience. Grotowski’s actors so not use furniture and props naturalistically, but with the imaginative spontaneity of a child and the sophistication of a disciplined artist. For them the floor becomes the sea, a table becomes a boat, the bars of a chair become a prison cell not to extend the narrative but as part of an interior drama. For Grotowski is concerned to expose the spiritual process of the actor. Techniques Grotowski placed great stress upon discipline, technique and training. He believed that acting was not just a job, but a way of life. He demanded that actors give themselves completely to their work and believed that the true nature of acting is in the search for self-knowledge; actors need to fulfil their true potential as human beings. His training was designed to give the actor great physical and vocal skills, and to teach them to break free from the limitations they placed on themselves. (notes from: Experimental Theatre from Stanilavski to Peter Brook by James Roose – Evans pub:Routledge and Kegan Paul ‘86 2. "We do not want to teach the actor a predetermined set of skills or give him a 'bag of tricks'...everything is concentrated on the 'ripening' of the actor...by a complete stripping down, by the laying bare of one's own identity.... The actor makes a total gift of himself. This is a technique of the 'trance' and of the integration of all the actor's psychic and bodily powers which emerge from the most intimate layers of his body and his instinct." Grotowski (Poor Theatre) Evoking Silence Actors had to remain in total silence for several minutes, with no outside noises to ultimately experience internal silence. This he called creative passivity. By evoking silence, they could concentrate intensely. His actors also trained in silence except when sounds or speech were essential parts of the activities. Physical Training This is the basis of Grotowski’s training. His actors had to learn extraordinary physical skills, which allowed them to control every move they made, even the smallest, in every detail. His actors were required to turn their faces into twisted, frozen masks by using their facial muscles and often contort their bodies into strange, non-human shapes, or imitate the movements of animals. Voice Grotowski believed that actors must have well developed vocal and respiratory systems and use total respiration, breathing properly through the lungs, diaphragm, ribs and head in the correct order. As well as controlling their breathing, the actors also had to learn to focus their voices as though they were coming from different parts of their bodies and project them to different parts of the room. They had to develop full registers from high to very deep and improve their diction, so that they could speak with great clarity in a number of different ways, including singing, chanting and reciting poetry. The actors were also required to imitate all the sounds in the world around them, including machines, birds, animals, thunder and dripping water. Contact Grotowski believed that real harmony in human relationships, on and off the stage, only developed when people really learned to look at each other and listen to each other. He was asking for the development of a real awareness of others, a real sensitivity to them in everyday contact and also to be more aware of the impact they had on other people. In all our contacts with other people, we can concentrate on really looking and listening, on being completely aware of them, and then responding to what we are actually seeing and hearing. Transformation In his Poor Theatre, Grotowski aimed always for the simplest, possible use of staging, lighting, costumes and special effects. It was then up to the actor to use all their skills to transform empty spaces and simple objects into a whole range of imaginative worlds. Simple items like a chair or a piece of cloth could be transformed a dozen times during the course of a play, representing real objects like an executioner’s block, or being used as symbols, such as a piece of white cloth for purity. In Akropolis, the costumes for the prisoners in the concentration camp were simply old bags with holes torn in them. The insides of the bags were lined with red material which looked like torn flesh. Memory Like Stanislavski, Grotowski emphasized the use of emotion memory to recall an experience and recreate the feeling that went with that memory. But he demanded total honesty and commitment; they had to be prepared to make use of all memories, no matter how painful. Truth Grotowski demanded total commitment and belief in every activity, even the simplest exercise. He expected the actors to carry that kind of belief and commitment with them at all times. They were expected to look for the real truth in their daily lives and relationships, and act completely honestly according to that truth. (notes from: Living Drama 2nd Ed. By Bruce Burton. Pub.Longman Cheshire 1991)