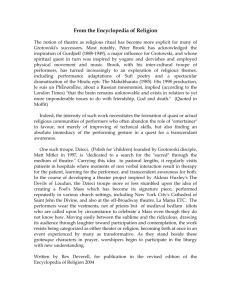

Ecstasy: a Source of Intimacy or Applications of the Dionysiac Model

advertisement

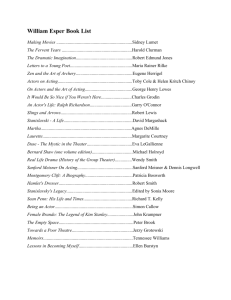

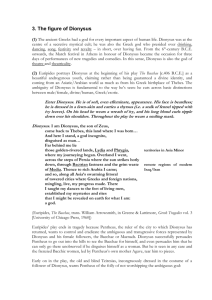

Ecstasy: a Source of Intimacy or Applications of the Dionysiac Model for Grotowski’s Theatre Anna Misopolinou The idea for my thesis and therefore for this article, was born of a sense of frustration. As fanciful or commonplace as it may sound, the truth is that even though I think that theatre represents an ideal, I have seen too many performances in which ‘nothing happens’. Of course there was a plot and a director, there were actors, etc, but there was no ‘soul’. Once I had an acting teacher in Greece who shared my feelings and challenged us, the class, by taking us to observe a ritual called Anastenaria. I will give more details about this later in the article, but in short, it is a Greek custom in which the participants dance until in a trance and then walk over burning coals. They are not ordinary people. They all have the same origins and most of them are descendants of people who used to perform the same ritual. Anyway, I remember noticing how intimate the participants were with each other and how they concentrated on what they where doing, even though they have performed the same ritual time after time! I also remember a participant talking to me about the curiosity of the visitors who come to the village and ask questions, ‘ They ask what will happen to me. How should I know? I don’t know. May it be God’s will that I dance again this year!’ That was the key thought for me. They did not take their actions for granted. Every year, every day, they were equally motivated to participate, to see what would happen. Would they avoid getting burned once more? They have done it so many times, but that makes no difference. Every time it is something new. This is what I feel is from the theatre. This is what I call ecstasy: this moment of ambiguity, which makes the person creative. It is a term hidden in a very old Cult, the cult of Dionysus. It was also used, along with other notions, by a very modern theatre, Jersy Grotowski’s. I would be very happy if I could define a ‘know-how’ of ecstasy so to make it transferable to all sorts of theatre, but since it has as many forms as many people that exist on this planet, this is almost impossible. So I have to limit the scope of my research, in the hope that each of us can, afterwards, sense it, although not necessarily define it, wherever it flourishes. Therefore, I regard ecstasy as the Greek form of liminality, practised in the Dionysiac Cult. Arnold van Genep describes liminality as the second of a three-stage process, which one can observe in the rites of passage (1908:65115). During the intervening liminal period, the characteristics of the ritual subject are ambiguous since the condition and the person who is the subject in this, elude or slip through the network of classifications that normally locate states and positions in cultural space. According to Victor Turner ‘liminal entities are neither here nor there; they are betwixt and between the positions assigned and arrayed by law, custom, convention, and ceremony….liminality is frequently likened to death, to being in the womb, to invisibility, to darkness, to bisexuality, to the wilderness’ (1969:95). Ecstasy is perceived as the threshold in between oppositions. It is considered to be a state where life itself is phased out of the limits dualism sets. The aim of the Dionysus’ cult, as E,R. Dodds stresses, was ecstasy, which again could mean anything from ‘taking you out of your self to profound alteration of personality (1951:77)’. In etymological terms, ecstasy derives from the Greek word ek-stasis [‘out’ + ’place’]. Put into personal terms, a person who is subject to ecstasy is taken out of ‘what he’s been placed in’ either by himself or the social context in which he grew up, as defined by conventions, customs, social rules and regulations, habits and even principles. By being taken out of the context, one is invited to speculate and criticise. Ecstasy is the will to abandon comfort in pursuit of self-knowledge. Dionysiac ecstasy borders between consciousness and unconsciousness, sanity and madness, exalted purity and abandonment, strength and weakness. Turner stresses the productive role of this liminal phase: Prophets and artists tend to be liminal and marginal people, "edgemen", who strive with a passionate sincerity to rid them selves of the cliches associated with status incumbency and role-playing and to enter into vital relations with other men in fact or imagination. In their productions we may catch glimpses of that unused evolutionary potential in mankind which has not yet been externalized and fixed in structure (1969:128). Similarly, one purpose of ecstasy is to allow the individual to lose his/her sense of reality, but only momentarily. It occurs in a limited time and space and under given rules and techniques. It could be expressed as a spontaneous and eruptive feeling, but the individual never loses awareness of him/herself. S/He always ‘comes back’ to be a vital and creative member of his society. It is not an outsider activity. Ecstasy is a state in which liberation along with growth and maturity is allowed. Richard Schechner describes this as ‘not myself’ yet ‘not not myself’ (1985:4). In theatrical terms the former is the blueprinted role whereas the latter the realized role. In ritual terms the former is the neophyte in an ecstatic ritual, whereas the latter is an experienced participant. Both the participant in Dionysiac rites and actors have the opportunity to re-evaluate the standards and redefine him/herself so that each of his/her expressions is genuine. Grotowski calls his actors to come into ecstasy, to knock down their barriers so to allow the impulses to be expressed (1968:15-26). Flazsen, according to Kumiega, describes in a poetic way Grotowski’s productions aim: Grotowski’s productions aim to bring back the utopia of those elementary experiences provoked by collective ritual, in which the community dreamed ecstatically of its own essence, of its place in a total, undifferentiated reality, where Beauty did not differ from Truth, emotion from intellect, spirit from body, joy from pain; where the individual seemed to feel a connection with the Whole of being. (Flazsen in Kumiega 1985:156) I maintain that Grotowski’s work was based on the way ecstasy functions in the Dionysiac Cult. For the purpose of methodology, I introduce the idea of the Dionysiac Model (or the circle of ecstasy). It is a spiral process with three main and three secondary stages (SUFFERING – madness – DEATH – Catharsis – RESURRECTION – Transformation) which interact with each other. The Model shows the different phases via which an individual is allowed into ecstasy for the purpose of coming into communion with him/herself and others. The Model was formed by: a) the Dionysiac Myth itself as it has survived in modern literature through the ancient sources (I do not use primary sources for the reason that my knowledge of ancient Greek is inadequate to approach such texts. On the other hand, I avoid using a translation whose accuracy I can not check. Therefore, I used the modern literature by well-known scholars to eliminate inconsistency); b) the practice of the Dionysiac Cult in ancient Greece, Bacchic (1) ceremonies and especially institutions such as the Eleusinian Mysteries; and c) the modern practice of the Dionysiac cult. There is an ecstatic, Greek rite called Anastenaria and it has Dionysiac origins. The data was selected primarily through field-work. There is also a small, yet sufficient body of literature on this ritual. I will continue presenting the way I composed the Dionysiac Model and will then move on to explain the particular terms of the model and give the specific definition they take in this research. Firstly, I will examine the Dionysus Myth. There are two versions of the myth. According to the first, Dionysus is the son of Zeus and Persephone, Demeter’s daughter. She, as the goddess of the underworld, together with her mother are the main figures of the Eleusinian Mysteries. In this legend, the Titans, Zeus’ predecessors, tore Dionysus into 7 pieces after his birth. Demeter saved him by joining the pieces together. In the second version he is the son of Zeus and Semely, princess of Thebes. Semely, while she was pregnant and persuaded by the jealous Hera, asked Zeus to appear to her in his real form. So he did; he came to her in all his glory as a thunderbolt. Semely was burnt to death but Zeus sewed the premature baby in his thigh and let it live. Some versions of the myth identify Semely’s virtues with those of Persephone. In addition to this there are other stories about the god as an adult, which indicate again the same pattern. The one who suffers, dies and eventually rises from the dead. The most useful and indicative example of the practice of the Dionysiac cult is the Eleusinian Mysteries. The Mysteries were initiatory institutions within the ancient Greek religion. They were inaugurated in-between 1580 and 1500 BC and celebrated at Eleusis for nearly 2000 years. Literature attributes the Mysteries to Demeter and Persephone. Yet Persephone was considered to be the female counterpart of Dionysus. Some scholars, such as Eliade, and Kerenyi maintain that the Mysteries expressed the Dionysiac spirit, which is the spirit of endless self – knowledge (Eliade,1978:290-301; Kerenyi,1951:190-256). In the Mysteries, through mental and emotional tasks the human condition, as Eliade claims, was modified (1978). To what extent and how this happened can not be proven but it could scientifically be assumed. The same scholar says that the initiate (mystes) at first wanders into darkness and undergoes all sorts of terrors; then is struck by a marvelous light and discovers pure regions and meadows, hears voices, and sees dances. There he feels bliss and happiness. In the Mysteries the ordeals of the initiate are compared with the experiences of the soul immediately after death. I have to point out that it was a secular institution where everybody, including women, could participate. Also, the participants did not form any kind of ‘church’ so as to develop an eccentric way of viewing life. Thus it is irrational to assume that all these people for so many years were solemnly concerned with life after death! They must have derived a benefit for their present life, which can be assumed by the pattern of the initiation: pursuit in darkness – subjection to all sorts of terrors – enlightenment – bliss. I conclude that the mystes, to use a modern expression, had a kind of break-down so as to re-evaluate themselves. In any case, this was written at the entrance of the temple: "self–knowledge". As such we are not far from the SUFFERING DEATH – RESURRECTION Model. Here, though, some secondary terms are introduced: the break-down is a type of madness, and Dionysus is in any case the god who drives people insane. Also, enlightenment and bliss is a way to catharsis, which means ‘cleansing’. Finally the initiate becomes a ‘new’ person. ‘ A birth in death is something that must be termed ‘ mystic’ in the ancient sense since the Mysteries revolved around such birth’, says Kerenyi (1976:108). We discover the same essence in Grotowski’s words: ‘This is not instruction of a pupil but utter opening to another person, in which the phenomenon of "shared of double birth" becomes possible. The actor is reborn – not only as an actor but as a man…’ (1968:25). More specifically, Lisa Wolford, who worked with Grotowski for many years, claims that: ‘In "Art as Vehicle", Grotowski’s aim is far more radical; he (re)appropriates the means and structure of performance to serve an explicitly esoteric goal, establishing a type of performance practice that attempts to reconstitute certain elements associated with Orphic and Eleusinian Mysteries’ (1996:16). Based on this I suggest that theatre might well be a process of initiation. The third source I used for constructing the Dionysiac Model is Anastenaria. It is a Greek ritual in which people dance until in a trance and eventually walk over burning coals. The custom, brought by immigrants from Nothern Thrace in the early twentieth century, takes place in some villages in the north of Greece. It occurs twice a year, in January, when it lasts for three days, and in May when it lasts for four days. It is considered by the participants to be a part of the Greek Orthodox practice but all the scholars who have researched this ritual, with the exception of a few whose conclusions are considered to be of minor importance, maintain that Anastenaria is clearly a survival of Bacchic Cult. This opinion is mainly based on a) the observable similarities between the enactments in Anastenaria and of those in the Dionysiac worship in ancient Greece; b) the geographical factors, which are the same both for Dionysus and the practice of Anastenaria; c) the trance-like state reached by both maenads and the participants in Anastenaria; and d) the same symbolism. Observing their dance one can see that the participants, especially when they are neophytes, are in an agony of suspense, uneasiness and agitation. They let out screams of grief and even when not dancing, are not aware of the presence of others. Eventually they step onto the coals where they curse Evil with the words - ‘May it turn into ashes!’ After the firewalking they seem released and happy, smiling and talkative. The above, with the details I will give later in this article, demonstrate that especially in Anastenaria we can observe the Dionysiac model in all its phases of SUFFERING–Madness–DEATH–Catharsis–RESURRECTION– Transformation. The ultimate goal for the participants in the Dionysiac ritual is the Communion with the ‘God’. This is more or less the aim of all traditional rituals. The difference in the Dionysiac cult is that ‘God’ could be translated as the primitive instincts and impulses of the persons involved. I will move on now, on one hand, to explain each term of the Dionysiac Model and at the same time to show the type of events and actions, which are included in each of the stage of the Model. To do this I will present the way each term operates in the Dionysiac Cult and in Grotowski’s acting techniques. SUFFERING is the first stage of the ecstatic process in which the subject endures a mental, emotional or physical pain or effort. The cause is either undefined or brought about by physical, external circumstances, which exhaust the body, that is, cause the SUFFERING. The goal is for the participant to release emotions of distress, agitation, anger and discomfort in a primitive way. In the Dionysiac Cult the participants performed frenzied dances for the whole night. Dionysus represents all these primitive elements within the human condition, which need to be expressed. Resistance to them could prove to be harmful as they can erupt in inappropriate circumstances. The easiest way for an individual to release them is through an elementary activity such as dance accompanied by vocal sounds or just screaming. In Anastenaria the participants perform a very simple dance based on a cyclical pattern which lasts for many hours before it culminates in the firewalking. There is also another side to this ritual, particularly important for this study. There are references by the participants, quoted by Loring Danforth, that they suffered from depression or they had even had nervous break-downs before starting to participate in this ritual (1979:141-163). Their initiation to this ecstatic dance proved to be a cure for their condition. Also, when they first started dancing it was painful to enter the trace-like state. When I see them dancing it seems as if most of them are trying to rid themselves of something that tortures them from inside. Grotowski seemed to have been fully aware of the fact that for the impulses to be unblocked the exhaustion of the body is necessary. ‘One must begin with movement to burn off the energy, to set fire to the body, a kind of letting-go. It is as if your animal body becomes master of the situation and starts to move - without obsession about what is dangerous or not’ (1996a:262). He also maintains that, ‘When we find the courage to do things that are impossible, we make the discovery that our body does not block us’ (1996b:222). Koniordou (1999), a very famous Greek actress and a teacher of mine, recalls an exercise she did with Flaszen, Grotowski’s own colleague. She told me that he asked them to run in a circle to a fast rhythm for more than half an hour. She said that even if she had been an athlete, under normal circumstances, she couldn’t have done it. What happened there was that the group was coordinated into a common rhythm, which surpassed the individual’s limited possibilities. Despite this, it is common knowledge that Grotowski’s actors were trained for hours on end and were given exceptionally hard exercises to do. Similarly, in the Mysteries, the peregrination in darkness gave considerable agony to the initiates. On a symbolic level, the outer darkness is the inner one, which could be defined as all the primitive and unexpressed elements of the human condition. I am not saying that there is no other way for them to be expressed, so that an individual could a healthy existence with them. I am suggesting, though, that the body, as it has less complicated reactions than the mind, can be a handy vehicle for access to those levels. This condition of physical and mental exhaustion could legitimately result in a loss of the individual’s hold on the clarity of those relations on which he depends. This is what I call madness. It is important though to remember that this type of ecstatic madness lasts only for a limited period of time and it is always encouraged in a protected environment such as a ritual, an institution, or a rehearsal room. Walter Otto describes Dionysus as the mad god of wildness who, at the same time, can be a blessed deliverer because when madness is released it can be productive and a source of joy (1965:65, 143). Madness is the state where the person can not define himself as an individual, nor does he know where he stands and what for. Since, as Grotowski says, we base our existence on things we have been involved with at a particular time (1996c:81-86); we came to an agreement with them without having chosen them consciously, ‘at this point one can get lost in a sort of primitivism: one works on the body’s instinctual elements losing control of oneself’ (1996d:297). So when one losses control, one creates space to reevaluate old habits and inhibitions. This is an indispensable step to the next stage, which is DEATH. DEATH is used here as a metaphor. It is a state of transition, where the individual abandons the undesirable elements uncovered in the state of madness. ‘In this instance death is an abolishment of the barriers, the classes, the exclusions, not by syncretism, but by simply getting rid of this old spectre: Logical contradiction’ (Roland Barth, 1970:77). The psychologist Abraham Maslow, who did a comprehensive study on ecstatic experiences, calls them ‘a little death’ and a rebirth in various senses (1982:9). For him ‘death is not to be sought first at the end of life, but at its beginning…it [death] attends all of life’s creations’. Ecstasy is a reconciliation with death, an understanding of its necessity. For Grotowski what one should ‘kill’ is the dressing, the covering, the possessing. For him actors should be ‘burned alive’ like martyrs. Death is not a condition; rather, it is a process in which, as the Polish director says, ‘what is dark in us slowly becomes transparent. In this struggle with one’s own truth, this effort to peel off the life-mask, the theatre, has always seemed to me a place of provocation’ (1968:21). In the Mysteries, the initiates seem to have gone through a type of ‘death’ as the ceremony manifests the Persephone’s/Dionysus’ resurrection circle. According to the myth, both the deities descent to the under world to come back in the Spring. The anastenarides (the participants in Anastenaria) try to extinguish the fire with their feet when they step on the coals as, in this way, they believe they will kill evil and diseases. It is interesting for one to observe their behavior on the last night of the fiesta, when everything is finished. The same people who, on the first days are quite reserved, especially on the second day before the firewalking, are talkative and telling jokes on the night of the last day, and their eyes portray a sublime serenity, (describing such a phenomenon cannot but sound somewhat subjective). Of course, it does not apply to all the participants and not every time to the same people. This is what I define as practiced catharsis. It is a term formed in the frame of ancient Greek Tragedy. It always arrives after death and destruction. It is the moment when the individual stands ‘naked’ in front of his/her own truth. Usually it is not pleasant. It depends on the level of self-realization the person has reached. Marcel Dettiene comments in relation to this, ‘the more insanity is unleashed the more room there is for catharsis’ (1989:21). In Grotowski’s Productions’ period, he seems to have ignored the necessity of this stage, which is crucial for the mental as well as the physical health of the people involved in such a process. The catharsis comes when the intensity of work, trial or ceremony calms down. It is necessary for there to be a time lapse from the events to allow catharsis to happen. It was only from the time of the theatre of Sources onwards that Grotowski recognized the necessity of people joining his training for a long, yet limited, period of time. The participants in the Mysteries, upon conclusion of the actual days when the institution operated, returned to their occupations, which could have been anything from writers of tragedy to simple labourers or political figures. The same applies to the anastenarides. I conclude that, when a process is so intense and arouses such strong and contradictory feelings, then, the participant should be given some space and time to consolidate his/her personal conclusions. If rushed, then the participant becomes an employee of the ‘masks’ instead of an employer of them. Presumably, when catharsis operates as ‘cleansing’, it is a step towards self-realization. The individual involved comes in contact with new options for his behaviour. As such, to use a metaphor, he is re-born from his own ashes. RESURRECTION is the final state of the Dionysiac Model process, in which the individual can define a reasoning for his actions, his thoughts or his feelings, better than he could before he entered this process. Adrian Del Caro comments on this in Friedrich Nietzche’s work, ‘in the Nietzchean philosophy the work of destruction and creation is carried out under the auspices of a conscious, philosophical Dionysus, whose mission or ‘purpose’ is the transvaluation’ (1981:18). The results are always relative to the previous condition of the individual. Moreover, the results are never final or ultimate. It is a spiral process, not a cyclical one. I have to mention, though, that the outcome of such a process does not always derive from a ’conscious and philosophical Dionysus’. The individual involved might just experience relaxation and enjoyment, by ‘letting off steam’, which again provides him with a clearer frame of mind. Referring to the actor, Grotowski says that, ‘when he begins to penetrate, through a study of his body’s impulses, the relationship of this contact, this process of exchange, there is always a rebirth in the actor’ (1996e:39). For Grotowski this process results in directness, drive and joy; thus, referring to the life of a child - We forgot about this state through the years of taming our body and with it out mind. It is necessary to refind this hypothetical child and his "ecstasies". Which, long ago, we "abdicated", as Baudelaire said, if I well remember. It is something tangible, organic, primal (1996a:258). The main symbol of the Eleusinian Mysteries was a child, too. I kept notes from the anastenarides saying, after the fiesta is finished, ‘I feel young again’. The aim of this process is not for the participant to go back to his childhood consciousness, but to regain the openness of a child, preserving though the maturity of an adult. The actor in this case avoids ‘mechanical’ acting (a term introduced by Stanislavski and used again by Grotowski) and discovers the truth of the character in its own self. The individual or the actor transforms him/herself into a role instead of reforming the role for him/herself. Dionysus is the god of many faces, the god of the mask. To him is attributed the original masks of Tragedy and Comedy. On a symbolic level this is translated as the life mask. The mask one wears for the different faces of one’s social life, without consciously using them. The question is for the individual to be aware that behind the mask is hidden the sincerity of the person, who has the privilege to choose the masks instead of being chosen by them. The ultimate purpose of this process is to prepare a fertile ground for Communion. In terms of Dionysiac rituals, the aim is reunion with the deity, which as we explained before is reunion with one’s own self. I also quoted Grotowski’s words which claim that the person changes not only as an actor, but as a man, too. This is the one side of the coin with the name Communion. The other is what Grotowski describes, very poetically again, as the goal of his theatrical work: ‘to cross the frontiers between you and me; to come forward to meet you, so that we do not get lost in the crowd – or among words, or in declarations, or among the beautifully precise thoughts’ (1996b:221). So, on one hand there is self-penetration, on the other the person/actor shares the experience with others. The Dionysiac Model, meaning the ecstatic process, is not a self-consuming one. It conveys the results to others, to a kind of audience so that the experience can be exchanged and recognised. This is apparent in Dionysus worship. Dionysus is a secular god, and his worshipers formed a ‘thiasos’, meaning a group of people who together experienced the nature of the deity and invite more people to do so by their example. The Bacchic frenzy dances, where simple citizens along with the authorities participated, were a way to worship Dionysus. A good example can be found in Euripides’ Bacchae. Also Dithyrambes were songs which were performed by the worshipers of Dionysus in front of an audience. The Dionysiac rites aimed at achieving communication between the god with the vast crowd. How similar to Grotowski’s aim to communicate human sincerity to the audience! This communion, apart from the spatial dimension (ME–YOU), also has a temporal one. It attempts to join the past with the present and therefore with the future. In the course of the Anastenaria ceremony, the participants claim to come in contact with their ancestors, who were also anastenarides, and the saints who protect the ritual. They also try to pass the custom on to the younger generations to affirm the unity and the continuity of the community. The element in this ritual which applies to theatre is what the master of the ceremony said to us, the spectators, last year, ‘Do come next year; Anastenaria without spectators do not exist’. The ritual becomes, on one hand, a verification of the participants’ identity, and on the other, an opportunity for the spectator to join it when he feels ready. Grotowski, in the course of his career considered it essential for more and more people to become involved with his work. People who come and go, would keep the process alive. He suggested a theatrical tradition. Also, even though he abandoned his ‘Productions’ period, he only stopped performing in a mainsteam way. In the ‘Art as Vehicle’ he gave performances in front of groups from different cultures and in this way they exchanged performances. He did not just refer to everybody in the spirit of ‘to whom it may concern’. For Grotowski ‘ritual is performance, an accomplished action. Degenerated ritual is a show’ (1996d). It is significant that his work, in its last phase, did not have the middle of a trendy metropolis as its location. The same happens with Anastenaria. One has to have a reason or desire to go there unless one happens to live in the area. I conclude that a theatre following the Dionysiac Model, as Grotowski’s theatre appears to have done, becomes an instructive entertainment as well as a life-long process based on very old traditions, such as the Dionysiac. Friedrich Nietzche while suggesting that the Dionysiac spirit is the creator of art and especially theatre, he also observes that this spirit is to an extent lost. Yet he remains optimistic: The struggle of the spirit of music to become manifest in image and myth – a struggle that grew in intensity from the beginnings of lyric poetry to the flowering of Attic tragedy – came to a sudden halt and disappeared, as it were, from the Hellenic scene. Yet the Dionysiac world view born of this struggle managed to survive in the Mysteries, and even in its strangest metamorphoses and debasements did not cease to attract thoughtful minds. Who knows whether that conception will not once again rise as art from its mystical depths (1956:104). The answer to this could have been given by the Polish director, who wrote: ‘I do not look to discover something new, but something forgotten ‘ (Grotowski, 1996f:374). The Theatre, as Grotowski suggested, can become a cradle for such a tradition to be born again. This tradition does not need a certain type of theatre to flourish. It does need, however, the right mentality. This can only be created within a tradition. Then theatre could become a magnate for eruptive creativity. Tradition comes from the past, but if we bear in mind that the present will at some point become the past, then, a ‘tradition’ can very legitimately start now. Notes 1. Bacchos is another name for Dionysus. Also Bacche or maenad were alternative names for Dionysus’ female followers who formed trance dances and orgies. References Barth, Roland (1970) p. 77 in C. Segal Dionysiac Poetics and Euripides Bacchae. London: Princeton. Danforth, Loring (1979), "The role of dance in the ritual therapy of Anastenaris". Byzantine and Greek Studies, 5:141-163. Detienne, Marcell (1989), Dionysus at Large. USA: Harvard University Press. Del Caro, Adrian (1981), Dionysian Aesthetics: The Role of Destruction in Creation as Reflected in the Life and Works of Friedrich Nietzsche. Frankfurt: Peter Lang. Dodds, E. R.( 1951) The Greeks and The irrational. California: University of California Press. Eliade, Mircea (1978), From the Stone Age to the Mysteries of Eleusis. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. Genep, Van (1908) The rites of Passage. California: The University of California Press. Grotowski, Jersy (1968) Towards a poor Theatre. London: Methuen. Grotowski, Jersy (1996a) "The Theatre of Sources" (1980) pp. 258, 262, in The Grotowski Sourcebook. London: Routledge Grotowski, Jersy (1996b) "Holiday"(1972) pp. 221-2, in The Grotowski Sourcebook. London, Routledge, 1996. Grotowski, Jersy (1996c) "I said Yes to the Past": Interview with Grotowski (1969) pp. 81-85 in The Grotowski Sourcebook. London: Routledge,. Grotowski, Jersy (1996d) "Tu es Fils de Quelqu’unin" (1989) p. 297, in The Grotowski Sourcebook. London: Routlege. Grotowski, Jersy (1996e) "Interview with Grotowski" by Richard Schechner and Theodore Hoffman (1969) p. 39, in The Grotowski Sourcebook. London: Routledge. Grotowski, Jersy (1996f) "The Performer"(1990) p. 374, in The Grotowski Sourcebook. London, Routledge. Kerenyi, Karl (1951) Introduction to the Science of Mythology. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd. Kerenyi, Karl (1976) Dionysus: Archetypal Indestructible Life. London: Princeton. Images of Koniordou, Lydia (1999). Personal communication. Kumiega, Jennifer (1985) The Theatre of Grotowski. London and New York: Methuen. Maslow, Abraham (1982) Religious experiences. New York: Penguin Books. Values and Peak- Nietsche, Friedrich (1956) The Birth of Tragedy and The Genealogy of Morals. New York: Anchor. Otto, Walter (1965) Dionysus: Myth and Cult. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. Schechner, Richard (1985), Between Theatre and Anthropology. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. Turner, Victor (1969) The Ritual Process. New York: Aldine De Gruyter. Wolford, Lisa (1996) "Ariadne’s Thread: Grotowski’s journey through the theatre" p. 16, in The Grotowski Sourcebook. London: Routledge,. Anna Misopolinou Ph. D. Student Goldsmiths College University of London Email: misopoli@agro.auth.gr Scholar of State Scholarships Foundation of Greece