Differential Safety Behavior Effects

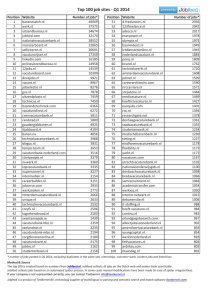

advertisement